Most of the entries on this page are collected from my Dreamwidth blog, but I ceased blogging there at the end of August; you can jump to post-Dreamwidth entries here.

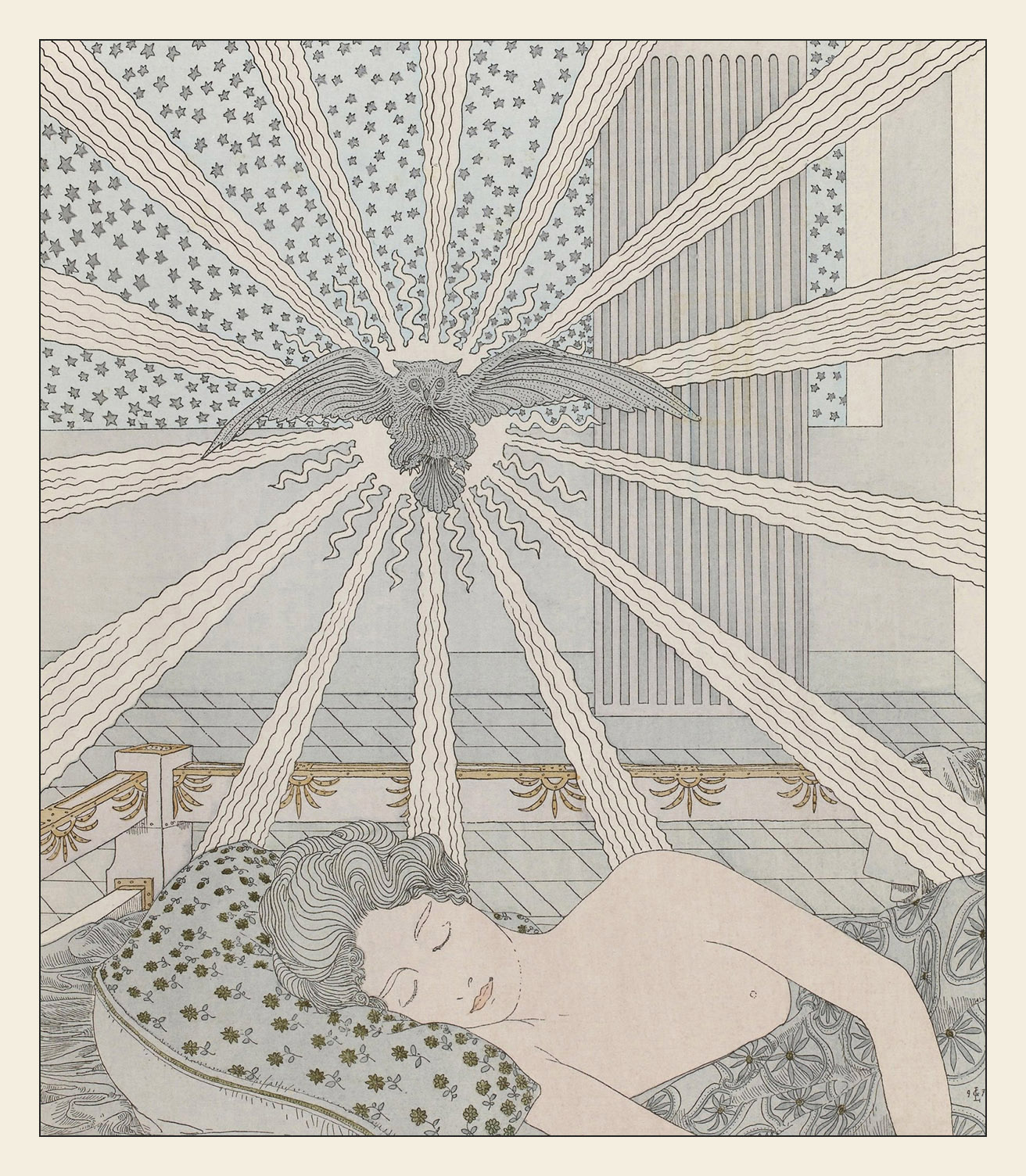

I have often seen it said in both occult texts and descriptions of NDEs that souls, when born into a body, are given not a single death-date, but two, which they may choose between during their mortal life. I’ve always wondered where the doctrine came from.

It occurs to me just now that maybe it comes from the mysteries, after all:

μήτηρ γάρ τέ μέ

For my mother φησι

says θεὰ

(the goddess Θέτις

Thetis ἀργυρόπεζα

silver-footed)

διχθαδίας κῆρας φερέμεν θανάτοιο

that I carry two different angels of death τέλος δέ.

for my end:

εἰ μέν

if κ’ αὖθι μένων

I should stay here Τρώων πόλιν ἀμφιμάχωμαι,

and besiege the Troian city,

ὤλετο μέν μοι νόστος,

then my return is lost, ἀτὰρ

but κλέος

my fame ἄφθιτον ἔσται:

will be enduring;

εἰ δέ

but if κεν οἴκαδ’ ἵκωμι

I should go home φίλην ἐς πατρίδα γαῖαν,

to my beloved fatherland,

ὤλετό μοι κλέος ἐσθλόν,

then my good fame is lost, ἐπὶ δηρὸν δέ

but long μοι αἰὼν

my life

ἔσσεται,

will be, οὐδέ κέ μ’ ὦκα

and not soon shall τέλος θανάτοιο

the end of death κιχείη.

reach me.

(Akhilleus speaking. Homeros, Ilias IX 410–416.)

Personally, I would take this to describe how an initiate must decide whether to spend their efforts on material accomplishments or spiritual accomplishments, since the two are mutually exclusive, but I can see how one might take it otherwise.

Plotinos has a line (at the end of Enneads IV ii §2) which has haunted me ever since I first read it:

ἔστιν οὖν ψυχὴ

So then, soul is ἓν

one καὶ

and πολλὰ

many οὕτως·

in this way;

τὰ δὲ ἐν τοῖς σώμασιν εἴδη

the forms within bodies are πολλὰ

many καὶ

and ἕν·

one; τὰ δὲ σώματα

bodies are

πολλὰ μόνον·

only many; τὸ δ’ ὑπέρτατον

but the highest is ἓν μόνον.

only one.

He was speaking of his emanative principles, but I think it applies just as clearly to Empedocles’s roots. Bear with me as I try to explain.

First, forget everything that modern science has taught us about atoms, molecules, gravity, planets, the solar system, etc. Try to think of the universe the way somebody might have three thousand years ago. At the “bottom” of everything is the Earth; above that, Water flows in rivers and lakes and the sea; above that, Air fills the void; and somewhere way above is Fire, the Sun. We think of each of these things as made of particles and such, but the ancients wouldn’t have: the Sun is a single “thing;” Air isn’t something that can be divided up, it’s more of a space-filling continuum; Water can be divided but it can just as easily be joined back together and tends to act as a unit; Earth, however, once divided isn’t easily put back together again. And so we see that Plotinos’s distinction seems applicable: Fire is one thing only; Air is one thing but it occupies many places; Water is many things but acts as one thing; Earth is many things only.

Next, consider each of these with respect to light. Fire emits light; Air transmits light freely, without distortion; Water transmits light, but it distorts it with refractions and reflections; Earth, however, does not transmit light at all, and merely receives it.

Are you with me so far? I hope I’m making sense.

The magic trick is to equate light and consciousness. Fire is the image of God, who is the source of all consciousness: just as the Sun illuminates all, so too does God experience all (and, indeed, all experience is God’s). Light travels freely through the Air in many directions, and this is the image of Heaven, where God’s one consciousness pervades all angels, allowing for individualized consciousness but still acting as one; God sees and acts as one through many eyes; this consciousness is as yet unreflective and unselfconscious, but moves and moves rightly as God wills. Water, however, introduces distortions to light and may be physically separated; God’s will can be turned to the individuals’ wills, and beings may join together and act as one or separate and act individually as they choose. Earth, finally, does not transmit light, but only receives it; the body is a dead thing, unconscious, merely acting as a container for Water.

Because it only acts as a container, beings cannot have Earth-consciousness. Beings with Water-consciousness (whether possessing an Earthy body or not) have the two peculiar properties that they can be self-conscious, on the one hand, and may choose to align or not with God’s purposes, on the other. Beings with Air-consciousness are not self-conscious or reflective (though this is not to say without unique characteristics), and convey only God’s light to all, acting as one, naturally and without effort. And, of course, there is only one Fire-consciousness, and it simply is.

Thus we see our five gods: fiery Osiris simply is, innocent and pure; airy Seth is divisive only insofar as he is the medium for individual consciousness; earthy Isis and watery Nephthus are always working together, mother supporting and nurse nourishing; and bright Horos is the light which shines from Osiris through and onto all.

Thus we also see our three worlds: fire, air, and our muddy Tartaros. If you wish to leave Tartaros, it isn’t enough to leave the body behind: you must clear your water so as to transmit light as clearly and as naturally as possible, with as little need of self-conscious reflection as possible (though I think it takes lots of self-conscious reflection to get to that point). Is this way you diminish the individual will and allow God’s will to operate through you. One can do that with or without a body, and so the body becomes vestigial, allowing one to join the angels. Plotinos says (Enneads III v §2) that there is no marriage in heaven, but this seems to me to have the emphasis backwards: there, all things are joined together.

Many years ago, while I was studying Zen, I misquoted Ruth Fuller Sasaki in my diary: “Only when one has no things in their mind and no mind in their things are they unearthly, empty, and marvelous.” (I didn’t write down the source or the original quote, alas.) But the misquote has stuck with me and I feel like I’m finally beginning to understand it.

I think it is important to note that, while every Greek hero-myth concerns itself with exile and return, in the Egyptian hero-myth, Horos never leaves Egypt.

𓅃

My last post reminded me of something I read what feels like three lifetimes ago. I went looking for it and found it.

“I have a memory of you when you were five and I was just making my profession. [... We] tried to pass the hour in a children’s game you made up. You told me I was a princess and had been put inside a jail that was just four walls and a locked door. And I was to try and get out. ‘I’ll scream for help,’ I said, ‘and a handsome prince will save me.’ And you said, ‘There’s no one around to hear you.’ ‘Well then,’ I said, ‘I’ll kick at the door until it breaks.’ But you said, ‘The door’s made of iron and you can pound and pound but it won’t be hurt.’ ‘I’ll look on the floor and find a key,’ I said, and you said I could indeed do that, but the key wouldn’t fit the lock. And I said, ‘You’re making this so difficult, Mariette.’ You asked if I really and truly wanted to get out, and I told you that I did. And then you said, ‘The jail has no ceiling. And you have wings. And you fly.’”

(Ron Hansen, Mariette in Ecstasy II.)

Akhilleus returns to the killing-fields of Troia. Apollon encourages prince Aineias to step up and fight him but Akhilleus’s armor, newly-forged by Hephaistos himself, is impervious to his blows. Akhilleus is just about to kill Aineias when Poseidon spirits him away from battle. Akhilleus raves (Ilias XX 344–352):

ὢ πόποι ἦ μέγα θαῦμα τόδ’ ὀφθαλμοῖσιν ὁρῶμαι:

ἔγχος μὲν τόδε κεῖται ἐπὶ χθονός, οὐδέ τι φῶτα

λεύσσω, τῷ ἐφέηκα κατακτάμεναι μενεαίνων.

ἦ ῥα καὶ Αἰνείας φίλος ἀθανάτοισι θεοῖσιν

ἦεν: ἀτάρ μιν ἔφην μὰψ αὔτως εὐχετάασθαι.

ἐρρέτω: οὔ οἱ θυμὸς ἐμεῦ ἔτι πειρηθῆναι

ἔσσεται, ὃς καὶ νῦν φύγεν ἄσμενος ἐκ θανάτοιο.

ἀλλ’ ἄγε δὴ Δαναοῖσι φιλοπτολέμοισι κελεύσας

τῶν ἄλλων Τρώων πειρήσομαι ἀντίος ἐλθών.

Here is how Samuel Butler translates it:

Alas! what marvel am I now beholding? Here is my spear upon the ground, but I see not him whom I meant to kill when I hurled it. Of a truth Aeneas also must be under heaven’s protection, although I had thought his boasting was idle. Let him go hang; he will be in no mood to fight me further, seeing how narrowly he has missed being killed. I will now give my orders to the Danaans and attack some other of the Trojans.

This is hot garbage. It’s slow, it’s flat, and it conveys none of Akhilleus’s fury or personality. (His own best friend, Patroklos, called him “a dreadful man, who would be quick to blame even the innocent!”) My favorite, W. H. D. Rouse’s, is a little better but still not very good:

Confound it all, here’s a miracle done before my eyes! There lies my spear on the ground, and not a trace can I see of the fellow I meant to kill! Aineias must have some friends in heaven. And I thought his boasting was all stuff and nonsense! Let him go to the devil. He won’t have a mind to try me again after this happy escape from death! All right, I will round up our people and have a try for some other Trojans.

Rouse argued vehemently, and I more-or-less agree, that Homeros wasn’t trying to be high literature: the Ilias was meant to be a rousing story told over beer. Sure, it contains dignified history and theology, but it was not, itself, meant to be dignified—it was meant to be exciting enough to buy the bard another day’s meal and lodging. But I think Rouse dropped the ball, here.

Here’s how I’d translate it:

What the fuck kind of magic is this!?

Here’s my spear lying on the ground, but I can’t

see the man I meant to kill with it.

So Aineias really is dear to the immortal gods!

I thought he was just bullshitting me.

Eh, fuck it: he won’t have the guts to face me

again, happy to have cheated death once.

Come on, I’ll rally the bloodthirsty Danaans

to go and try some other Troian face-to-face.

Compared to the others, it may look like I’m taking liberties, but it’s nearly word-for-word...

(If you don’t like his language, let me remind you we’re talking about man-baby Akhilleus and not, say, goody-two-shoes Diomedes or family-man Hektor!)

Κασσάνδρα.

Kassandra. ὀτοτοτοῖ πόποι δᾶ.

[incoherent screaming] Ὦπολλον Ὦπολλον.

O Ruin! O Ruin... [...]

Ἄπολλον

Ruin, Ἄπολλον ἀγυιᾶτ᾽,

Guiding Ruin, ἀπόλλων ἐμός.

my ruining!

ἀπώλεσας γὰρ οὐ μόλις τὸ δεύτερον.

Twice now you have utterly ruined me...

(Aiskhulos, Agamemnon 1072-82.)

I’m not much of a theater person, but Aiskhulos’s Kassandra is harrowing. I’ve checked something like five translations and, while I’m no expert, nobody seems to translate her well. And honestly I just don’t think she can translate well: she’s incoherent, rambling, and everything she says seems to have a double or triple meaning. Here, Aiskhulos explicitly connects Ἄπολλον “Apollon” (the god) with the virtually identical ἀπόλλων “destroying utterly” (the action), referring to how Apollon despoils the material world in favor of the spiritual (cf. Horos beheading Isis; Perseus from πέρσευς “pillager [of cities];” etc.) as he has also despoiled Kassandra. Ἄπολλον ἀγυιᾶτα “Apollon of the Roads” refers how Apollon guides initiates on the upward ways but also how he has guided Kassandra to her undoing. One gets the impression of a failed initiate, who saw but was unable to digest what she had seen and was broken by it.

By the Hellenistic era, Apollon was a joyful singer of songs; but to Homeros, Apollon was a harsh warrior. I wonder if his golden lyre was only for his heroes; his golden arrows were for everyone else...

I think I’ve found the mistake that I’ve been making: I’ve been mixing and matching my myths up! I have noted that the Horos-myth concerns growing up and gaining one’s inheritance, while the Greek myths concern exile-and-return, but I’m starting to think that these are not two different takes on the same idea; rather, I think they’re two different myths and I have been conflating them.

Let me start somewhere else and hopefully it’ll become clear as we go. No less than Hesiodos tells us that the Thebaian Wars and the Troian War are the two major events of the age of Heroes:

In the former, Europe was snatched away from Tyre to Crete, and her son Kadmos left Crete (simultaneously by choice and compulsion) to found Thebai, which was ruled by his descendents. Eventually, Thebai was besieged by the Seven, who failed (with six of the Seven dying), and the Epigone (their “offspring,” including Diomedes and Eurualos), who successfully sacked the city ten years later, carrying Europe’s magic necklace and robe and Manto away.

In the latter, Helene was snatched away from Argos to Troia (simultaneously by choice and compulsion) by Paris. The Danaans sent an envoy to Troia, and when that failed, they (including Diomedes and Eurualos) besieged it for ten years (during which many of their heroes died), eventually sacking the city and carrying Helene and Kassandra away.

Mythically speaking, though, these have the same meaning: the stories of both follow largely the same events, with the only meaningful difference between them being that individuals in the Troia myth are represented by bloodlines in the Thebai myth. We see a very similar story in the Theseus myth, too: the Athenian Youths are snatched away from Athens to the labyrinth (mostly unwillingly, though Theseus by choice). He enters the labyrinth, slays it’s inhabitant, and carries the Athenian Youths and Ariadne away. (It is noteworthy that labyrinths are called “Troy-Towns” in England and Scandinavia to this day.)

These don’t follow the pattern of the Horos myth, since Horos never leaves Egypt; instead, he avenges his father and claims his birthright. So if Horos represents one category of myth (the Hero-myth), I think the three above constitute a second one; let’s call it the City-myth.

Now, I’ve been looking at a bunch of myths so far, and treating them all as following the Hero-myth model. But I think this is a miscategorization and causes problems. The Perseus and Orestes myths clearly follow the Hero-myth model. The Odusseus myth does too, but only if we treat the Odusseia as self-contained, treating the Odusseus of the Ilias as a separate mythic character.

But Kore of the Persephone-myth isn’t Horos, she’s Europe! Just as Europe is beguiled by Zeus-as-a-bull and a crocus, Kore is beguiled by Hades (the “Khthonic Zeus”) and a narcissus. Just as Helene is snatched away to the house of Paris, Kore is snatched away to the house of Hades. Here, though, the envoy from Olumpos (that is, Demeter and her attendants) manage to secure a truce rather than the house of Hades being destroyed. (That is, it covers the first half of the myth but not the last half.)

There’s another City-myth I haven’t discussed: the Aesir-Vanir War and Ragnarok. Here, Freyja goes (by choice?) to Asgard, the Vanir send an envoy, and the war ends in a truce with Freyja being held hostage by the Aesir. Then things settle for a long time before Asgard is eventually destroyed during Ragnarok (a second, separate war mostly involving the children of the first war, like with Thebai). Frustratingly, while there are tantalizing similarities (for example, Freyja has the Brisingamen and a magic cape, matching Europe’s magic necklace and robe), what remains of the Asgard myth—or at least my understanding of it, from my light studies so far!—seems fragmentary...

Now, while I think these are separate myths, there is an interesting way these fit together. The first half of the Hero-myth (that is, concerning Osiris, Danae, etc.) matches the City-myth: beautiful and wonderful Osiris being Europe, Helene, the Athenian Youths, Kore, Freyja, etc., but the second half of the Horos-myth has nothing to do with it. Now, Thebai, Troia, the labyrinth, Asgard, etc. are all obviously the material world in which we live. Horos is born of Isis (in the material world), so if we’re looking for a Horos-equivalent in the City-myth, we’re looking for someone on the “side” of the city (rather than an invader) and who avoids it’s destruction (since Horus is not present for any city’s destruction). (That is, even though Homeros treats the Danaans as the protagonists of his tale, we should be wary of them, since we are the Troians!) There was exactly one Troian hero who survived the sack of Troia: Aineias, son of Ankhises and Aphrodite, most pious of the Troians, called “hero” by Apollon himself, and most beloved by the gods. I think he’s our Horos, and the parallel is made explicit by Dionusos of Halicarnassos, who tells us that Aineias’s father warns him before Troia falls, causing him to withdraw to Ida; this is the direct correspondence with Osiris coming to Horos from Hades, and is the point at which the Hero-myth diverges from the City-myth: with the City going on to its destruction while Horos goes on to do something else.

There’s two things interesting about Aineias. First, I’ve always considered Virgil’s Aenead to be a second-rate knock-off of the Odusseia, but if I’m right and Aineias is Horos, then this makes sense, since the Odusseus of the Odusseia is also Horos, and thus they ought to tell the same myth. Second, I had been assuming that Baldr was the Germanic equivalent of Apollon or Horos, but Snorri Sturluson identifies Aineias as Víðarr, slayer of Fenrir and one of the only Aesir to survive Ragnarok, and who goes on to found a new city. Thus, presumably Víðarr is also Horos; and if (as Ploutarkhos says) that Seth is to be identified with the eclipse, then Fenrir (who gobbles up the Sun) is presumably Seth (or, more likely, one of his avatars, perhaps the red bull Horos fights).

In the same way, I assume Daidalos (successful) and Ikaros (cautionary) are the Horos-equivalents in the Theseus myth, literally taking on wings and leaving the labyrinth behind to its fate.

Please consider this a first-draft conjecture, there are many, many details that I have yet to chase down, but it resolves the discrepancies that have been nagging at me.

It also carries with it the uncomfortable thought that Troia has not yet fallen: the material world is still here, the old gods are not yet dead. Hesiodos is unclear on the end of the Heroic age and the beginning of the Iron age—they seem to blend together—but on the basis of his descriptions of the end of the Iron age, the Voluspa’s descriptions of the prelude to Ragnarok, and of course my own theories that the old ways remain open (but probably not for much longer), the sack of Troia presumably comes soon. I urge to you to keep a weather eye out for Troian horses and to heed the warning of Laocoon which prompted Ankhises and Aineias to flee:

Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes.

I fear the Danaans, even those bearing gifts.

Some follow-on notes to my realization that Helene/Europe/Persephone/etc. are Osiris rather than Horos:

You remember how I (following, I think, Pythagoras and Empedocles) likened Osiris to Fire? Helene (Ἑλένη) is from ἑλένη “torch.” Similarly, Ploutarkhos derives Phersephone (Φερσεφόνη) from φαεσφόρος “light-bringing” (On the Man in the Moon XXVII).

You remember how Osiris’s name in Egyptian is a little throne next to a little eye (𓊨𓁹), meaning “the seat of the eye” (that is, the root of our consciousness, god-consciousness)? Europe (Εὐρώπη) is from εὐρύς “wide, broad” and some form of ὁρᾶν “to see,” indicating something very similar (that god-consciousness sees all at once).

@boccaderlupo noted that different myths lead to different outcomes (and commented that the Christians preserved the Ilias and Odusseia because they echo the exile-and-return theme that is so central to Christianity).

Piggybacking off of that, I wonder that if it is not only different myths but different interpretations of those myths that lead to different outcomes (under the assumption, of course, that those interpretations are guided from above, rather than from below). As I’ve noted before, the Isis and Demeter myths have identical structures, but the philosophers interpreted Persephone as the exile-and-return of the individual soul, while the Egyptians had no such interpretation, so far as I can tell, for Horos. But is that wrong? On Apollo’s authority, it clearly worked out okay for Puthagoras, Platon, and Plotinos; and while I have no such authority for the many, many, Christian saints since then, I see no reason to think it didn’t work for them, either!

That is all to say, I’m inclined to think that different Shepherds are happy to use the same tools in different ways...

Happy Ares-day!

Since so many asked me to, and I’ve never tried my hand at translating a lengthy section, I figured I’d go ahead and give it the old college try... but yipes! this took forever, and, anticipating that, I went rather more quickly than usual (managing a dozen lines a day); so it’s probably a lot less precise than I usually strive for. Consider it a first draft!

103

105

110

161

176

180

185

190

195

200

256

260

265

270

275

280

285

290

295

300

305

309

310

313

315

320

325

330

335

340

345

350τὸν δ’ αὖτε προσέειπεν ἄναξ Διὸς υἱὸς Ἀπόλλων:

ἥρως ἀλλ’ ἄγε καὶ σὺ θεοῖς αἰειγενέτῃσιν

εὔχεο: καὶ δὲ σέ φασι Διὸς κούρης Ἀφροδίτης

ἐκγεγάμεν, κεῖνος δὲ χερείονος ἐκ θεοῦ ἐστίν:

ἣ μὲν γὰρ Διός ἐσθ’, ἣ δ’ ἐξ ἁλίοιο γέροντος.

ἀλλ’ ἰθὺς φέρε χαλκὸν ἀτειρέα, μηδέ σε πάμπαν

λευγαλέοις ἐπέεσσιν ἀποτρεπέτω καὶ ἀρειῇ.

ὣς εἰπὼν ἔμπνευσε μένος μέγα ποιμένι λαῶν,

βῆ δὲ διὰ προμάχων κεκορυθμένος αἴθοπι χαλκῷ. [...]

Αἰνείας δὲ πρῶτος ἀπειλήσας ἐβεβήκει

νευστάζων κόρυθι βριαρῇ: ἀτὰρ ἀσπίδα θοῦριν

πρόσθεν ἔχε στέρνοιο, τίνασσε δὲ χάλκεον ἔγχος.

Πηλεΐδης δ’ ἑτέρωθεν ἐναντίον ὦρτο λέων ὣς [...]

οἳ δ’ ὅτε δὴ σχεδὸν ἦσαν ἐπ’ ἀλλήλοισιν ἰόντες,

τὸν πρότερος προσέειπε ποδάρκης δῖος Ἀχιλλεύς:

Αἰνεία τί σὺ τόσσον ὁμίλου πολλὸν ἐπελθὼν

ἔστης; ἦ σέ γε θυμὸς ἐμοὶ μαχέσασθαι ἀνώγει

ἐλπόμενον Τρώεσσιν ἀνάξειν ἱπποδάμοισι

τιμῆς τῆς Πριάμου; ἀτὰρ εἴ κεν ἔμ’ ἐξεναρίξῃς,

οὔ τοι τοὔνεκά γε Πρίαμος γέρας ἐν χερὶ θήσει:

εἰσὶν γάρ οἱ παῖδες, ὃ δ’ ἔμπεδος οὐδ’ ἀεσίφρων.

ἦ νύ τί τοι Τρῶες τέμενος τάμον ἔξοχον ἄλλων

καλὸν φυταλιῆς καὶ ἀρούρης, ὄφρα νέμηαι

αἴ κεν ἐμὲ κτείνῃς; χαλεπῶς δέ σ’ ἔολπα τὸ ῥέξειν.

ἤδη μὲν σέ γέ φημι καὶ ἄλλοτε δουρὶ φοβῆσαι.

ἦ οὐ μέμνῃ ὅτε πέρ σε βοῶν ἄπο μοῦνον ἐόντα

σεῦα κατ’ Ἰδαίων ὀρέων ταχέεσσι πόδεσσι

καρπαλίμως; τότε δ’ οὔ τι μετατροπαλίζεο φεύγων.

ἔνθεν δ’ ἐς Λυρνησσὸν ὑπέκφυγες: αὐτὰρ ἐγὼ τὴν

πέρσα μεθορμηθεὶς σὺν Ἀθήνῃ καὶ Διὶ πατρί,

ληϊάδας δὲ γυναῖκας ἐλεύθερον ἦμαρ ἀπούρας

ἦγον: ἀτὰρ σὲ Ζεὺς ἐρρύσατο καὶ θεοὶ ἄλλοι.

ἀλλ’ οὐ νῦν ἐρύεσθαι ὀΐομαι, ὡς ἐνὶ θυμῷ

βάλλεαι: ἀλλά σ’ ἔγωγ’ ἀναχωρήσαντα κελεύω

ἐς πληθὺν ἰέναι, μηδ’ ἀντίος ἵστασ’ ἐμεῖο,

πρίν τι κακὸν παθέειν: ῥεχθὲν δέ τε νήπιος ἔγνω.

τὸν δ’ αὖτ’ Αἰνείας ἀπαμείβετο φώνησέν τε:

Πηλεΐδη μὴ δὴ ἐπέεσσί με νηπύτιον ὣς

ἔλπεο δειδίξεσθαι, ἐπεὶ σάφα οἶδα καὶ αὐτὸς

ἠμὲν κερτομίας ἠδ’ αἴσυλα μυθήσασθαι. [...]

ἀλκῆς δ’ οὔ μ’ ἐπέεσσιν ἀποτρέψεις μεμαῶτα

πρὶν χαλκῷ μαχέσασθαι ἐναντίον: ἀλλ’ ἄγε θᾶσσον

γευσόμεθ’ ἀλλήλων χαλκήρεσιν ἐγχείῃσιν.

ἦ ῥα καὶ ἐν δεινῷ σάκει ἤλασεν ὄβριμον ἔγχος

σμερδαλέῳ: μέγα δ’ ἀμφὶ σάκος μύκε δουρὸς ἀκωκῇ.

Πηλεΐδης δὲ σάκος μὲν ἀπὸ ἕο χειρὶ παχείῃ

ἔσχετο ταρβήσας: φάτο γὰρ δολιχόσκιον ἔγχος

ῥέα διελεύσεσθαι μεγαλήτορος Αἰνείαο

νήπιος, οὐδ’ ἐνόησε κατὰ φρένα καὶ κατὰ θυμὸν

ὡς οὐ ῥηΐδι’ ἐστὶ θεῶν ἐρικυδέα δῶρα

ἀνδράσι γε θνητοῖσι δαμήμεναι οὐδ’ ὑποείκειν.

οὐδὲ τότ’ Αἰνείαο δαΐφρονος ὄβριμον ἔγχος

ῥῆξε σάκος: χρυσὸς γὰρ ἐρύκακε, δῶρα θεοῖο:

ἀλλὰ δύω μὲν ἔλασσε διὰ πτύχας, αἳ δ’ ἄρ’ ἔτι τρεῖς

ἦσαν, ἐπεὶ πέντε πτύχας ἤλασε κυλλοποδίων,

τὰς δύο χαλκείας, δύο δ’ ἔνδοθι κασσιτέροιο,

τὴν δὲ μίαν χρυσῆν, τῇ ῥ’ ἔσχετο μείλινον ἔγχος.

δεύτερος αὖτ’ Ἀχιλεὺς προΐει δολιχόσκιον ἔγχος,

καὶ βάλεν Αἰνείαο κατ’ ἀσπίδα πάντοσ’ ἐΐσην

ἄντυγ’ ὕπο πρώτην, ᾗ λεπτότατος θέε χαλκός,

λεπτοτάτη δ’ ἐπέην ῥινὸς βοός: ἣ δὲ διὰ πρὸ

Πηλιὰς ἤϊξεν μελίη, λάκε δ’ ἀσπὶς ὑπ’ αὐτῆς.

Αἰνείας δ’ ἐάλη καὶ ἀπὸ ἕθεν ἀσπίδ’ ἀνέσχε

δείσας: ἐγχείη δ’ ἄρ’ ὑπὲρ νώτου ἐνὶ γαίῃ

ἔστη ἱεμένη, διὰ δ’ ἀμφοτέρους ἕλε κύκλους

ἀσπίδος ἀμφιβρότης: ὃ δ’ ἀλευάμενος δόρυ μακρὸν

ἔστη, κὰδ δ’ ἄχος οἱ χύτο μυρίον ὀφθαλμοῖσι,

ταρβήσας ὅ οἱ ἄγχι πάγη βέλος. αὐτὰρ Ἀχιλλεὺς

ἐμμεμαὼς ἐπόρουσεν ἐρυσσάμενος ξίφος ὀξὺ

σμερδαλέα ἰάχων: ὃ δὲ χερμάδιον λάβε χειρὶ

Αἰνείας, μέγα ἔργον, ὃ οὐ δύο γ’ ἄνδρε φέροιεν,

οἷοι νῦν βροτοί εἰσ’: ὃ δέ μιν ῥέα πάλλε καὶ οἶος.

ἔνθά κεν Αἰνείας μὲν ἐπεσσύμενον βάλε πέτρῳ

ἢ κόρυθ’ ἠὲ σάκος, τό οἱ ἤρκεσε λυγρὸν ὄλεθρον,

τὸν δέ κε Πηλεΐδης σχεδὸν ἄορι θυμὸν ἀπηύρα,

εἰ μὴ ἄρ’ ὀξὺ νόησε Ποσειδάων ἐνοσίχθων:

αὐτίκα δ’ ἀθανάτοισι θεοῖς μετὰ μῦθον ἔειπεν:

ὢ πόποι ἦ μοι ἄχος μεγαλήτορος Αἰνείαο,

ὃς τάχα Πηλεΐωνι δαμεὶς Ἄϊδος δὲ κάτεισι

πειθόμενος μύθοισιν Ἀπόλλωνος ἑκάτοιο

νήπιος, οὐδέ τί οἱ χραισμήσει λυγρὸν ὄλεθρον.

ἀλλὰ τί ἢ νῦν οὗτος ἀναίτιος ἄλγεα πάσχει

μὰψ ἕνεκ’ ἀλλοτρίων ἀχέων, κεχαρισμένα δ’ αἰεὶ

δῶρα θεοῖσι δίδωσι τοὶ οὐρανὸν εὐρὺν ἔχουσιν;

ἀλλ’ ἄγεθ’ ἡμεῖς πέρ μιν ὑπὲκ θανάτου ἀγάγωμεν,

μή πως καὶ Κρονίδης κεχολώσεται, αἴ κεν Ἀχιλλεὺς

τόνδε κατακτείνῃ: μόριμον δέ οἵ ἐστ’ ἀλέασθαι,

ὄφρα μὴ ἄσπερμος γενεὴ καὶ ἄφαντος ὄληται

Δαρδάνου, ὃν Κρονίδης περὶ πάντων φίλατο παίδων

οἳ ἕθεν ἐξεγένοντο γυναικῶν τε θνητάων. [...]

τὸν δ’ ἠμείβετ’ ἔπειτα βοῶπις πότνια Ἥρη:

ἐννοσίγαι’, αὐτὸς σὺ μετὰ φρεσὶ σῇσι νόησον [...].

ἤτοι μὲν γὰρ νῶϊ πολέας ὠμόσσαμεν ὅρκους

πᾶσι μετ’ ἀθανάτοισιν ἐγὼ καὶ Παλλὰς Ἀθήνη

μή ποτ’ ἐπὶ Τρώεσσιν ἀλεξήσειν κακὸν ἦμαρ,

μηδ’ ὁπότ’ ἂν Τροίη μαλερῷ πυρὶ πᾶσα δάηται

καιομένη, καίωσι δ’ ἀρήϊοι υἷες Ἀχαιῶν.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ τό γ’ ἄκουσε Ποσειδάων ἐνοσίχθων,

βῆ ῥ’ ἴμεν ἄν τε μάχην καὶ ἀνὰ κλόνον ἐγχειάων,

ἷξε δ’ ὅθ’ Αἰνείας ἠδ’ ὃ κλυτὸς ἦεν Ἀχιλλεύς.

αὐτίκα τῷ μὲν ἔπειτα κατ’ ὀφθαλμῶν χέεν ἀχλὺν

Πηλεΐδῃ Ἀχιλῆϊ: ὃ δὲ μελίην εὔχαλκον

ἀσπίδος ἐξέρυσεν μεγαλήτορος Αἰνείαο:

καὶ τὴν μὲν προπάροιθε ποδῶν Ἀχιλῆος ἔθηκεν,

Αἰνείαν δ’ ἔσσευεν ἀπὸ χθονὸς ὑψόσ’ ἀείρας.

πολλὰς δὲ στίχας ἡρώων, πολλὰς δὲ καὶ ἵππων

Αἰνείας ὑπερᾶλτο θεοῦ ἀπὸ χειρὸς ὀρούσας,

ἷξε δ’ ἐπ’ ἐσχατιὴν πολυάϊκος πολέμοιο,

ἔνθά τε Καύκωνες πόλεμον μέτα θωρήσσοντο.

τῷ δὲ μάλ’ ἐγγύθεν ἦλθε Ποσειδάων ἐνοσίχθων,

καί μιν φωνήσας ἔπεα πτερόεντα προσηύδα:

Αἰνεία, τίς σ’ ὧδε θεῶν ἀτέοντα κελεύει

ἀντία Πηλεΐωνος ὑπερθύμοιο μάχεσθαι,

ὃς σεῦ ἅμα κρείσσων καὶ φίλτερος ἀθανάτοισιν;

ἀλλ’ ἀναχωρῆσαι ὅτε κεν συμβλήσεαι αὐτῷ,

μὴ καὶ ὑπὲρ μοῖραν δόμον Ἄϊδος εἰσαφίκηαι.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεί κ’ Ἀχιλεὺς θάνατον καὶ πότμον ἐπίσπῃ,

θαρσήσας δὴ ἔπειτα μετὰ πρώτοισι μάχεσθαι:

οὐ μὲν γάρ τίς σ’ ἄλλος Ἀχαιῶν ἐξεναρίξει.

ὣς εἰπὼν λίπεν αὐτόθ’, ἐπεὶ διεπέφραδε πάντα.

αἶψα δ’ ἔπειτ’ Ἀχιλῆος ἀπ’ ὀφθαλμῶν σκέδασ’ ἀχλὺν

θεσπεσίην: ὃ δ’ ἔπειτα μέγ’ ἔξιδεν ὀφθαλμοῖσιν,

ὀχθήσας δ’ ἄρα εἶπε πρὸς ὃν μεγαλήτορα θυμόν:

ὢ πόποι ἦ μέγα θαῦμα τόδ’ ὀφθαλμοῖσιν ὁρῶμαι:

ἔγχος μὲν τόδε κεῖται ἐπὶ χθονός, οὐδέ τι φῶτα

λεύσσω, τῷ ἐφέηκα κατακτάμεναι μενεαίνων.

ἦ ῥα καὶ Αἰνείας φίλος ἀθανάτοισι θεοῖσιν

ἦεν: ἀτάρ μιν ἔφην μὰψ αὔτως εὐχετάασθαι.

ἐρρέτω: οὔ οἱ θυμὸς ἐμεῦ ἔτι πειρηθῆναι

ἔσσεται, ὃς καὶ νῦν φύγεν ἄσμενος ἐκ θανάτοιο.

ἀλλ’ ἄγε δὴ Δαναοῖσι φιλοπτολέμοισι κελεύσας

τῶν ἄλλων Τρώων πειρήσομαι ἀντίος ἐλθών.But then Lord Apollon, the son of Zeus, said to [Aineias]:

“Pray, then, to the immortal gods—yes, even you, hero!*—

since they say that Aphrodite, the daughter of Zeus,

is your mother. That [Akhilleus] is of a lower degree of god,

for your mother is of Zeus, but his, merely the Old Man of the Sea.

Now, pick up your unwearying bronze, and don’t you let

him weary you* with curses or threats.”

Then he breathed great spirit into the prince,*

who went beyond the flashing bronze helmets of the vanguard. [...]

And Aineias stood menacingly out in front:

lowering his heavy helmet, holding his eager shield

in front of him, and brandishing his bronze spear.

Across the field, the son of Peleus prowled forth like a lion, [...]

and when they had drawn close to each other,

swift-footed, noble Akhilleus spoke first:

“Aineias!? Out of such a huge crowd, why did you come out

to make a stand? Were you itching to fight me*

in the hopes of being lord of the horse-taming Troians,

the pride of Priam? Even if you kill me,

it’s not like Priam would put the crown in your hands,

not while his sons are of sound body and mind.

Or maybe the Troians set aside some choice parcel

of good orchards and fields* for you to manage

if you kill me? I don’t think you’ll find it easy—

I seem to remember having already set you running scared of my spear!

Or had you forgotten that time you were separated from your cows

and I chased you down Mount Ida as fast as your feet could carry you?

You never even looked back as you ran!

You escaped to Lurnessos, but I set it

to the torch, having tracked you with Athene and father Zeus,

and I took away her women’s day of freedom*

and led them away.* Zeus and the other gods saved you then,

but I don’t think they’ll save you now, like you think they will;*

I urge you to go back

into the crowd instead of facing me man-to-man—

you might get hurt! ‘Only an idiot makes the same mistake twice.*’”

Then Aineias spoke in answer to him:

“Son of Peleus! You can’t hope to frighten me like a baby with your words,

since I, too, know how

to bitch and moan. [...]*

You will not turn me from the battle I desire

before we meet bronze-to-bronze. Come on, then—

let’s taste each other’s spears!*”

And with that he hurled his heavy, fearsome spear into that marvelous shield,*

and the great shield rang out from the impact.

With his strong hand the son of Peleus pushed the shield away from him

in alarm, since he foolishly thought the long spear

of heroic Aineias would pass right through it—

he didn’t realize, deep in his heart and mind,

that the glorious gifts of the gods are not easily

broken or turned aside by mortal men!

So the heavy spear of skillful Aineias did not

pierce that god-given shield, since the gold held;

even so, he drove it through two plates, but three

remained, since the Clubfoot* had forged it of five:

two of bronze, two of tin within those,

and [the middle] one of gold,* which held the ashwood spear.

Next, Akhilleus hurled his long-handled spear

and struck the circular shield of Aineias

on its edge, where the bronze and leather run thinnest,

and the the son of Pelias’s ashwood shot through

and the shield crashed under it.

Aineias shrank and flung his shield up

in fear, and the spear deflected over his back and stuck in the earth,

having sundered the two parts of the circle

of the massive shield.* Having dodged the hefty shaft, he

stood still, eyes wide in shock,

frightened that the missile grazed so near, while Akhilleus

quickly drew his double-edged sidearm* and pounced at him

with a fearsome roar, but Aineias seized a boulder in his hand—

a mighty deed! two men couldn’t have lifted it,

such as men are now, but he wielded it easily by himself—

then Aineias would have charged and thrown the rock

at helmet or shield, which would have kept [Akhilleus] from certain death,

and the son of Peleus would have closed and taken away his life with his sword,

had not Poseidaon Earth-Shaker seen it quickly

and immediately spoke his mind to the immortal gods:

“Damn, I ache for great-hearted Aineias,*

soon to be broken by the son of Peleus and descend to the house of Haides,

having let himself be persuaded by the words of Sniper Apollon—

foolishly, since [the god] won’t save him from a grim fate.

But why should this innocent pointlessly suffer

for others’ mischief, when he always

gives such nice gifts to the gods who hold the wide heavens?

How about we snatch him away from death?

The son of Kronos might also be angry if Akhilleus

cuts him down, since he is destined to escape [Troia],

lest the bloodline of Dardanos be destroyed or forgotten,

since he was the favorite of all the sons of Zeus

that were born to him of mortal women. [...]”

Then the cow-eyed queen Here answered him, saying:

“You do you,* Earth-Shaker, [...]

but as for us, we have sworn many oaths

before the immortals, little Athene* and I,

never to prevent a bad day for the Troians—

not even should all Troia be set alight and consumed by fire,

so long as the martial* sons of the Akhaians kindle it.*”

But when Poseidaon Earth-Shaker had heard this,*

he went on over the fighting and clash of weapons

and came to where Aineias and glorious Akhilleus were,

and he immediately poured a mist down over the eyes

of Akhilleus, son of Peleus, and drew the bronze-tipped ashwood

from the shield of greathearted Aineias

and set it at the feet of Akhilleus;

but Aineieas he spirited away, lifting him high above the earth.

And many ranks of heroes and horses both

were quickly passed over by Aineias in the hand of the god,

until he landed at the furthest of the many battle fronts,

where the Kaukonians were arming up for war.

Then Poseidaon Earth-Shaker came up beside him

and admonished him, piercing with words fletched as arrows:*

“Aineias! Who the hell ordered you to recklessly

face that madman son of Peleus’s in battle?

He’s both stronger and dearer to the immortals than you are!*

He ever comes near you, you run—

or else you’re going to the house of Haides no matter what your destiny is.

But when Akhilleus is dead and gone to his fate,

then take courage and fight at the forefront,

since he’s the only Akhaian that can beat you.”

He left Aineias there after saying all this

and dispersed the heaven-sent mist from Akhilleus’s eyes

so that he goggled

and ranted to himself:

“What the fuck kind of magic is this!?

Here’s my spear lying on the ground, but I can’t

see the man I meant to kill with it.

So Aineias really is dear to the immortal gods!

I thought he was just bullshitting me.

Eh, fuck it: he won’t have the guts to face me

again, happy to have cheated death once.

Come on, I’ll rally the bloodthirsty Danaans

to go and try some other Troian face-to-face.”

- Hero: ἥρως, literally “hero” in Greek, too. Hero comes from the Egyptian heru “falcon,” referring to the god Horos; that is, a “hero” is a little-H horos (rather than the big-H Horos). Many sources (Herodotos, Histories II cxliv; Diodoros, Library of History I xxv; Ploutarkhos, Isis and Osiris XII) equate Apollon with Horos, implying that Apollon is the god of heroes. If the god of heroes himself calls you a hero, I imagine you’re doing something right! In fact, Aineias is much beloved by the gods, being saved from certain death by each of Aphrodite, Apollon, and (as we see here) Poseidaon. He was also the only Troian hero to survive the fall of Troia.

- Weary you: the pun is mine; the Greek is ἀτειρέα “unable to be dulled” and ἀποτρεπέτω “turn you away.”

- Prince: ποιμένι λαῶν, literally “shepherd of his people.” Homeros has a higher opinion of nobility than I do, but then, I guess I always was more of a Hesiodos sort of guy!

- Itching to fight me: ἦ σέ γε θυμὸς ἐμοὶ μαχέσασθαι ἀνώγει, literally “did your heart command you to fight me?”

- Orchards and fields: Greek distinguishes “land planted with field crops” (wheat, barley, etc.) and “land planted with anything else” (e.g. orchards, vineyards, gardens, etc.), and these are the two kinds of land being described.

- Day of freedom: what a serendipitous turn of phrase!

- Led them away: this was when Akhilleus captured his favorite girl-toy, Briseis, the fight over whom started off the events of the Ilias.

- Like you think they will: ὡς ἐνὶ θυμῷ βάλλεαι, literally “as is set in your heart.”

- Only an idiot makes the same mistake twice: ῥεχθὲν δέ τε νήπιος ἔγνω, literally “even a child learns from experience,” but I wanted to clarify it since Akhilleus is implying that Aineias would be foolish to try his luck again.

- [...]: I know I make Aineias sound like a stoic, actions-speak-louder-than-words type of person here, but you should know that he goes on at excruciating length about the lineage of princes of Troia. He’s actually much more of a kinda square, by-the-book sort.

- Spears: χαλκήρεσιν ἐγχείῃσιν, literally “bronze-tipped spears,” but the excessive repetition of the word “bronze” was galling.

- That marvelous shield: the beautifully-crafted shield that Hephaistos, god of smiths, forged for him the night before and inlaid with beautiful imagery. Its description is one of the highlights of the Ilias, and can be found in XVIII 478–608.

- The Clubfoot: Hephaistos, who was born lame.

- [The middle] one of gold: gonna be honest, it seems pretty strange to use tin (which is brittle) and gold (which is both soft and very heavy) in a shield, especially on the inside where their corrosion-resistance and beauty aren’t on display!

- Massive shield: ἀσπίδος ἀμφιβρότης, literally “shield which covers both sides of a man.”

- Double-edged sidearm: ξίφος ὀξὺ, literally “sharp-pointed xiphos,” which was a backup weapon, a large dagger or short sword sharpened on both sides, meant for both slashing and stabbing.

- I ache for great-hearted Aineias: Throughout the Ilias, Poseidaon sides with the Akhaians. His regard for Aineias is therefore quite special!

- You do you: αὐτὸς σὺ μετὰ φρεσὶ σῇσι νόησον, “decide for yourself within your own heart.”

- Little Athene: Παλλὰς Ἀθήνη, usually transliterated “Pallas Athene,” but Παλλάς from πάλλαξ, “child below the age of puberty.” I suppose that’s why she’s always said to be a virgin...

- Martial: ἀρήϊοι, literally “of/like/devoted-to Ares,” which is the equivalent to “martial” (e.g. “of/like/devoted-to Mars”) in English.

- So long as the [...] Akhaians kindle it: sheesh, talk about vindictive!

- But when Poseidaon [...] had heard this: I like to think he rolled his eyes and gave an exasperated sigh before rushing off to save Aineias.

- Piercing with words fletched as arrows: φωνήσας ἔπεα πτερόεντα, literally “speaking feathered words,” usually translated “winged words.” Like “the wine-colored sea” of the Odusseia, this is one of those phrases that classicists have been arguing over forever. I can’t for the life of me tell why, since the meaning seems obvious enough?

- Dearer to the immortals than you are: yeah, maybe his mommy got him some fancy-pants armor, but you don’t see anybody rescuing Akhilleus from the battlefield, do you?

- To himself: πρὸς ὃν μεγαλήτορα θυμόν, literally “at his own mighty heart.”

(Homeros, Ilias XX 103–352, as translated—hopefully not too badly!—by yours truly.)

The reason why being a student is so great is that you can be wrong all you want and it’s not a problem—you just fix the mistake, learn something new, and off you go. Today was the first day in a while that I felt like I was capable of thinking well and so I spent a bunch of time reading and thinking about Apollodoros’s account of the Thebaian cycle, when I realized that the Horos myth does have an exile-and-return. In fact, it even has a city! It’s Bublos that is the equivalent of Thebai and Troia.

But it isn’t Horos that gets exiled, it’s Osiris; Horos is only “exiled” in the sense that his seed is contained within Osiris. Osiris is thus sort of the entire Greek host; his box being accepted into Bublos is not so very different from the Troian horse, and his coming back in fourteen pieces is like how the Greek host was scattered to the far winds in their returns.

But this means Aineias isn’t Horos. But it turns out I already knew our Horos: it’s Orestes, son of Agamemnon. (Which I suppose should have been obvious, since Orestes never goes to Troia, murders his mother, and avenges his father.) We see the same character in the Thebaian cycle in the figure of Alkmaion, who also murders his mother to avenge his father, is chased by the Erinues, undergoes purifications, etc.

But there were many heroes at Troia (and, indeed, at Thebai). I haven’t chased them all down, but the one who really stands out is Diktus, who almost leaves Bublos, but not quite; this one is Akhilleus, who was also nursed-but-not-really by a goddess by day and burned in a fire at night, and managed to survive most of the way through the war before succumbing to passion. (I’m sure he would have left Troia alive had Peleus not cried out upon seeing him burning!) And, while I’m not 100% sure of it, the most likely candidate for Aineias is actually old Teiresias, who led the Thebaians away before the Epigone sacked the city, helping them to found a new one.

Anyway, I’ve a long way to go, but I think there’s two takeaways from this. First, always treat your knowledge as provisional; there is always something to be learned by ditching your assumptions. Second, if I want to reconcile my myths, it won’t do to simply have a list of point-by-point in the stories: they actually form a sort of tree, with the core stem following Osiris-Horos, the house of Atreus, and Europe’s magical necklace, but with branches splaying off at various points depending on which hero we are talking about. This strengthens the hypothesis that the ancients knew there were many spiritual paths and tried to support them...

τὸ δ’ ἐν Σάει τῆς Ἀθηνᾶς [...] ἕδος

The plinth of Athena (=Neith) at Sais ἐπιγραφὴν εἶχε

has an inscription τοιαύτην

as follows:

“ἐγώ

“I εἰμι

am πᾶν

all τὸ γεγονὸς

that was καὶ

and ὂν

is καὶ

and ἐσόμενον

will be καὶ

and

τὸν ἐμὸν πέπλον

my dress οὐδείς πω θνητὸς

nobody mortal yet ἀπεκάλυψεν.”

has uncovered.”

(Ploutarkhos, Isis and Osiris IX.)

Ah, but there was a mortal who uncovered Athena’s dress (albeit accidentally): the great seer of Thebai, Teiresias. Many conflicting stories are told about him (her?), and I spent a few days trying to sort out his (their?) myth. Here is my best guess at a reconstruction, with a few observations:

Kadmos (“pre-eminent”) is led to the spot which would become Thebai by a cow with a moon-shaped spot on it. The nearby spring is guarded by a dragon; Kadmos slays it and, on the advice of Athene, sows its teeth. The teeth grow into a host of warriors, and Kadmos throws stones into the group, which causes them to attack each other until there are only five left, who pledge allegiance to Kadmos. One of these five, Oudaios (“from the ground”), has a son named Euerous (“well-built”). Euerous marries the nymph Khariklo (“famous for her beauty”), who is a favorite attendant of Athena, and they have a son, Teiresias (“prophet”). [Apollodoros, Library III iv, vi.]

Euerous is only said to be “of the line” of Oudaios, but two considerations require Teiresias to be within two generations of him: first, he is blinded some time before Kadmos’s grandson, Aktaion, is killed; second, Teiresias becomes seer to Kadmos, and so is at least partially contemporaneous with him.

Teiresias having one parent’s line being literally sprung from the earth and the other being divine has the same crucial resonance with other heroes, but perhaps none more than Aineias, who’s paternal grandfather was the brother of the founder of Troia (like how Oudaios was the close associate of the founder of Thebai), whose mother was Aphrodite (who, like Khariklo, is a divinity “famous for her beauty”), and who rescued those who could be from the sack of Troia.

One summer day, Athena, Khariklo, and young Teiresias are traveling through Mt. Helikon. Teiresias goes off to explore while Athena and Khariklo bathe in the spring of Hippokrene (“horse spring”). At some point, Teiresias comes back to the spring to get a drink, sees Athena naked, and is blinded for it by the law of Zeus. Athena is upset about this, but cannot override her father; so as to make amends to Khariklo, she gives Teiresias the gifts of prophecy, augury, long life, retaining his wits after death, and a magic staff of cornel-wood which would “guide his feet.” [Kallimakhos on the Bath of Pallas; Apollodoros, Library III vi.]

The Hippokrene is also where the Muses bathed before giving Hesiodos the gifts of an inspired voice and a staff of laurel-wood. [Hesiodos, Theogony 1–35.] Both seem to me reminiscent of how initiates of Osiris were purified and given heather stalks, or initiates of Dionusos were purified and given thursoi.

The Bath of Pallas, which gives wisdom even as it inflicts punishment, is, of course, life in the material world, which is almost always treated as a purification or cleansing of the soul. (Indeed, Empedocles’s famous poem on the topic, which I have used as the basis of my interpretation of the hero-myths, is called Purifications.)

Teiresias’s blindness and gifts, of course, are exactly the point of spirituality: one loses the ability to engage in the material world but gains the ability to engage in the spiritual world both now and after they die.

Kallimakhos explicitly links this story to that of Aktaion. Both beheld their patron deity naked (Athena for Teiresias, Artemis for Aktaion), but Teiresias made good of evil, while Aktaion did not. I wonder if seeing one’s patron naked is the point of no return in spirituality: after that, one must either cease to be mortal or cease to be—there is no longer a middle ground, and this is why Neith’s statue says that no mortal has uncovered her dress.

There is an alternate version of the story (made famous by Ovid) where Teiresias was blinded when he settled a bet between Zeus and Hera, saying that sex is ten times better for women than men. I dismiss this one out of hand, because it is of a popular nature and because spiritual teachings are unitive rather than divisive.

While traveling through Mt. Kullene, Teiresias comes upon two serpents entwined in sex and crushes them with his staff. This so incenses Hera that she changes Teiresias into a woman. Teiresias becomes a priestess of Hera, marries, and has a daughter named Manto (“prophecy”). At some point, Apollon tells Teiresias that if she comes upon a pair of serpents, to repeat her prior action, which happens in the eighth year after the first time, and she is changed back into a man. [Phlegon, Book of Wonders; Apollodoros, Library III vi.]

Mt. Kullene is the birthplace of Hermes, and his symbol, the kerukeion, is two serpents entwined around a staff. Even today we call androgynous people mercurial. Teiresias being initiated by Hermes (if only figuratively) and Athena is shared by other hero myths, like Perseus and Odusseus.

Surviving sources disagree about which serpent or serpents are crushed in each event. Most sources are either ambiguous or say both each time (and this is what I’ve followed), though others say that the female was crushed each time, or the female the first time and the male the second time. Whatever the case, the sex-change is an obvious reference to reincarnation; the killing of the serpents inadvertently is a symbol of dying without purpose, but the killing of the serpents intentionally is a symbol of dying with purpose. This is the same as the myth of Perseus, where the Gorgons (“grim things”) represent death; but while Stheno (“forceful”) and Euruale (“far-ranging”) are immortal, indicating that death cannot be overpowered or outrun, Medousa (“she rules”) is mortal, indicating that death doesn’t need to control us (and, indeed, can be put to good use—as Plotinos says, why should death trouble an immortal?). Therefore, Manto represents the realization of one’s true self, the soul which animates the body, which only comes through experience.

The serpentine symbolism is also present in the Kadmos myth, where he kills the serpent of Ares, serves Ares for eight years, marries Ares’s daughter Harmonia, and finally is transformed with his wife into a pair of serpents.

Archbishop Eustathios of Thessalonike, following an elegiac poet named Sostratos, tells an alternate version of the story in which Teiresias was born female and changed sexes six times before finally being turned into mouse (and presumably eaten by a weasel). I also dismiss this out of hand, because it is of a popular nature and is impossible to reconcile with both of the only reliable fixed points of the Teiresias’s life: his rescue of Thebai and the necromantic ritual of Odusseus.

When the Seven attack Thebai, the Thebaians ask Teiresias how they should be victorious, and he advises that if Menoikeus (“strength of the house”), son of Kreon, willingly sacrifices himself to Ares, that the Thebaians would be victorious, which he does and they are. Ten years later, when the Epigone attack Thebai and king Laodamas (“tamer of the people”) is killed by Alkmaion (general of the Argives), Teiresias advises the people to send a herald to negotiate with the enemy and secretly flee meanwhile, which they do. Apollon shoots him with an arrow as he drinks from the spring of Tilphoussa and he dies there, but the people continue on to found Haliartos (about fifteen miles from Thebai). Manto, however, is captured by the Argives and, since they had promised “the most beautiful of the spoils” to Apollon, send her to Delphi. She becomes a priestess of the god and he sends her to Colophon to found an oracle. There, she marries Rhakios (“rag”), and has a son by him, Mopsos, who is also a celebrated seer and the rival of Kalkhos in the Nostoi. [Pausanias, Descriptions of Greece VII iii, IX xviii, IX xxxiii; Apollodoros, Library III vi–vii, Epitome vi.]

Tilphoussa is the spring where Apollon first tried to institute his oracle, but the water nymph dissuaded him; after taking over the oracle at Delphi, he later returned and cursed the spring. [Homeric Hymn to Apollon 239–76, 375–87.]

I have a theory that the myth of the house of Kadmos represents the mysteries, just like the myth of the house of Atreus or the myth of the house of Atum. If that is so, then the reason why Teiresias participated in the seven generations of Thebai up to the epigone (Kadmos→Poludoros→Labdakos→Laios/Kreon→Oidipous→Polunikes/Eteokles/Ismene/Antigone→Laodamas/Thersandros) is because he participated in the mysteries and, having mastering these, he was able to, on the one hand, save the women and children of Thebai, and on the other, guide future heroes (e.g. Odusseus) on the way home.

Tilphoussa is on Mt. Tilphosium, which is right next to Mt. Helikon (which is where the Hippokrene was). There is something very Wizard of Oz about Teiresias’s life ending where it “began.”

That Teiresias (“prophet”) dies but Manto (“prophecy”) lives on to serve others is, of course, a common motif in spirituality and reminds me more of Plotinos than anyone.

Manto marrying Rhakios (“rag”) certainly shows how the mystery teachings are valued in the world: that is to say, not at all, and I wonder to what degree we possess the likes of Platon today because of his homosexual pedophilia, or Plotinos because nobody knew what to make of him, or Apollodoros because the mysteries were hidden in silly stories that nobody took seriously. Mopsos became celebrated precisely because he recognized the hidden value of those rags, though.

While lost at sea, Odusseus travels to Haides and summons Teiresias, now holding a golden staff, and receives advice on how to safely return home. [Homeros, Odusseia X–XI.]

I briefly mentioned Teiresias’s killing of the snakes and Perseus’s killing of Medousa as a reference to mastering the fear of death yesterday (note 3B). I spent some time searching up a favorite Zen story which I originally heard from D. T. Suzuki concerning the same thing:

Murakawa Soden tells the story that a certain vassal of the shogun once came to the great swordsmaster Yagyu Tajima no Kami Munenori and asked to become his student. Master Yagyu said, “You seem to already be very accomplished in some school of martial arts! First, tell me which school you’ve practiced under, and then we can make arrangements.”

The man replied, “But I have never practiced any martial arts.”

Master Yagyu said, “What, have you come to make fun of me? Do you think you can fool the teacher of the shogun himself?” But the man persisted, and so Master Yagyu said, “Well, I’ll believe you, but I insist that you must be a master of something. What is it?”

The man thought for a moment and said, “Ever since I was a boy, it seemed to me that a warrior should be somebody who is not afraid of death. Because of that, I have grappled with the problem of death for many years and now I no longer fear it. That’s the only thing I think I can honestly say that I have mastered.”

Master Yagyu was deeply impressed and said, “That’s it! I know a master when I see one. You see, the ultimate principle of swordsmanship is freedom from the fear of death. I have trained many hundreds of students, but until now, not a single one has mastered that final principle. You need no technical training. I will initiate you right now.” And he gave the man a certificate right then and there.

(Yamamoto Tsunetomo, Hagakure XI, as adapted from several translations by yours truly.)

ὤ μοι,

Oh my, τέκνον ἐμόν,

my child, περὶ πάντων κάμμορε φωτῶν,

unluckiest of all men,

οὔ τί

by no means σε Περσεφόνεια Διὸς θυγάτηρ ἀπαφίσκει,

is Persephoneia, the daughter of Zeus, deceiving you:

ἀλλ’

but αὕτη

this δίκη ἐστὶ

is how it is βροτῶν,

with mortals ὅτε

when τίς κε θάνῃσιν:

one should die,

οὐ γὰρ ἔτι

for no longer σάρκας τε καὶ ὀστέα ἶνες ἔχουσιν,

do sinews hold the flesh and bone,

ἀλλὰ τὰ μέν τε

but them πυρὸς κρατερὸν μένος αἰθομένοιο

the mighty force of burning fire

δαμνᾷ,

overcomes, ἐπεί

when κε πρῶτα λίπῃ λεύκ’ ὀστέα θυμός,

spirit should first leave the white bones,

ψυχὴ δ’

and soul, ἠύτ’ ὄνειρος

like a dream, ἀποπταμένη πεπότηται.

flutters up and away.

ἀλλὰ

But φόωσδε

to the light τάχιστα λιλαίεο:

anxiously hasten, ταῦτα δὲ πάντα

and all this

ἴσθ’,

remember, ἵνα

so that καὶ μετόπισθε

even afterwards τεῇ εἴπῃσθα γυναικί.

you can tell your wife.

(Antikleia speaking to Odusseus. Homeros, Odusseia XI 216–24.)

μὴ δή

Don’t μοι θάνατόν γε παραύδα,

talk to me about death, φαίδιμ’ Ὀδυσσεῦ.

Mr. Smarty-Pants.*

βουλοίμην κ’

I would rather ἐπάρουρος ἐὼν θητευέμεν

be a hired farmhand ἄλλῳ,

to another,

ἀνδρὶ

a man παρ’ ἀκλήρῳ,

of no land, ᾧ

who μὴ βίοτος πολὺς εἴη,

is of little substance,

ἢ

than πᾶσιν νεκύεσσι καταφθιμένοισιν

of all the downtrodden dead ἀνάσσειν.

be king.

Mr. Smarty-Pants: φαίδιμ’ Ὀδυσσεῦ, literally “brilliant Odusseus,” but I take this sarcastically, as immediately above (473–6) he says, “if you’re so clever, why the hell did you go to Hell?”

(Akhilleus speaking to Odusseus. Homeros, Odusseia XI 488–91.)

If we take Haides to be the material world, it really puts a different spin on Antikleia’s and Akhilleus’s words, doesn’t it?

Recall how I have been tracing two categories of myths: the city myth, and the hero myths that are embedded within the city myth? I think they describe two different categories of time: the city myth is cyclical, while the hero myth is linear. The city myth therefore describes the world, but the hero myth describes one’s experience within the world; and it must be noted that there are many heroes for a given city, each with different goals: some, like Ganumedes, are spirited away during the city’s lifetime; some, like Aineias and Teiresias, leave the city before it is destroyed to found a new one; some, like Horos and Orestes and Alkmaion, avenge their father who was betrayed while away at the city; some, like Perseus and Odusseus, merely find their way home.

But let me take a moment to describe why I think the city-myth is cyclic. If we look at the royal line of Thebai from it’s founding to it’s destruction, we see these seven generations:

| ↓ Kadmos Founds Thebai. Given necklace of Harmonia. ↓ | → | Oudaios Born from the earth. ↓ |

| Poludoros ↓ | Euerous ↓ | |

| Labdakos ↓ | Teiresias Lives for seven generations. ↓ | |

| Laios ↓ | ↓ | |

| Oidipous ↓ | ↓ | |

| Seven Against Thebai ↓ | ↓ | |

| Epigone Laodamas killed. Thersandros’s line continues on but leaves Thebai. The necklace is taken to Argos. × | Leaves Thebai to found Haliartos. ↓ |

We see a hero found the city, and then seven generations later, his line peters out, but a new hero arises and leads a remnant of the city to found a new city as the old one is destroyed.

Now, compare this to the Troian royal line:

| ↓ Dardanos Founds Dardanos. ↓ | |

| Erikhthonios ↓ | |

| Tros | |

| ↙ Ilos Founds Troia, which mostly subsumes Darnados. ↓ | ↘ Assarakos ↓ |

| Laomedon ↓ | Kapus ↓ |

| Priam ↓ | Ankhises ↓ |

| Hektor Zeus withdraws favor. Line ends. × | Aineias Leaves Troia and rebuilds it after the Akhaians sack it. ↓ |

This is very similar: a city is founded, the primary line dies, but a secondary line spawns a hero who founds a new city after the destruction of the first, seven generations later.

We see that many of these cities come from previously founded cities: Thebai is founded because Kadmos is barred from returning home; Haliartos is founded because Thebai is destroyed; Dardanos is founded because of a catastrophic flood that destroyed Arkadia; Troia is refounded after it is burned to the ground.

I think these indicate world ages, after which the old world is destroyed in fire and flood and a new one begins, just like Platon’s priest of Sais describes. I have mentioned that I wonder if the Horos-myth is a reaction to Atlantis; this would be a very natural result if Atlantis was the city of a prior age, just as Troia is the city of our age.

Βασιλεύς.

King Pelasgos. τὸ πάνσοφον νῦν ὄνομα τοῦτό μοι φράσον.

Now, tell me his masterly-devised name.

(Aiskhulos, Suppliant Maidens 320.)

ὣς ἄρα οἱ εἰπόντι

As he was saying so ἐπέπτατο δεξιὸς ὄρνις,

a bird flew towards him on the right,

κίρκος,

a falcon, Ἀπόλλωνος ταχὺς ἄγγελος:

the swift messenger of Apollon; ἐν δὲ πόδεσσι

and with its feet

τίλλε

it plucked πέλειαν

a pigeon ἔχων,

it was holding, κατὰ δὲ πτερὰ χεῦεν ἔραζε

and feathers fell to the ground

μεσσηγὺς

between νηός τε καὶ αὐτοῦ Τηλεμάχοιο.

Telemakhos and his ship.

(Homeros, Odusseia XV 525–8.)

I can’t believe I didn’t notice this before now! In Greek, κίρκος kirkos means “falcon” or “hawk,” obviously as suited to Apollon as it is to Horos. But this is the same word as Κίρκη Kirke, daughter of the Sun and initiator of Odusseus.

More translation practice! I’m getting a little faster: this batch was twenty lines a day! I find, as I read Homeros in Greek, that the stories’ connection to philosophy and the Mysteries is far more obvious than it is in translation, as so many of the words or phrases carry double meanings...

313

315

320

325

330

335

340

345

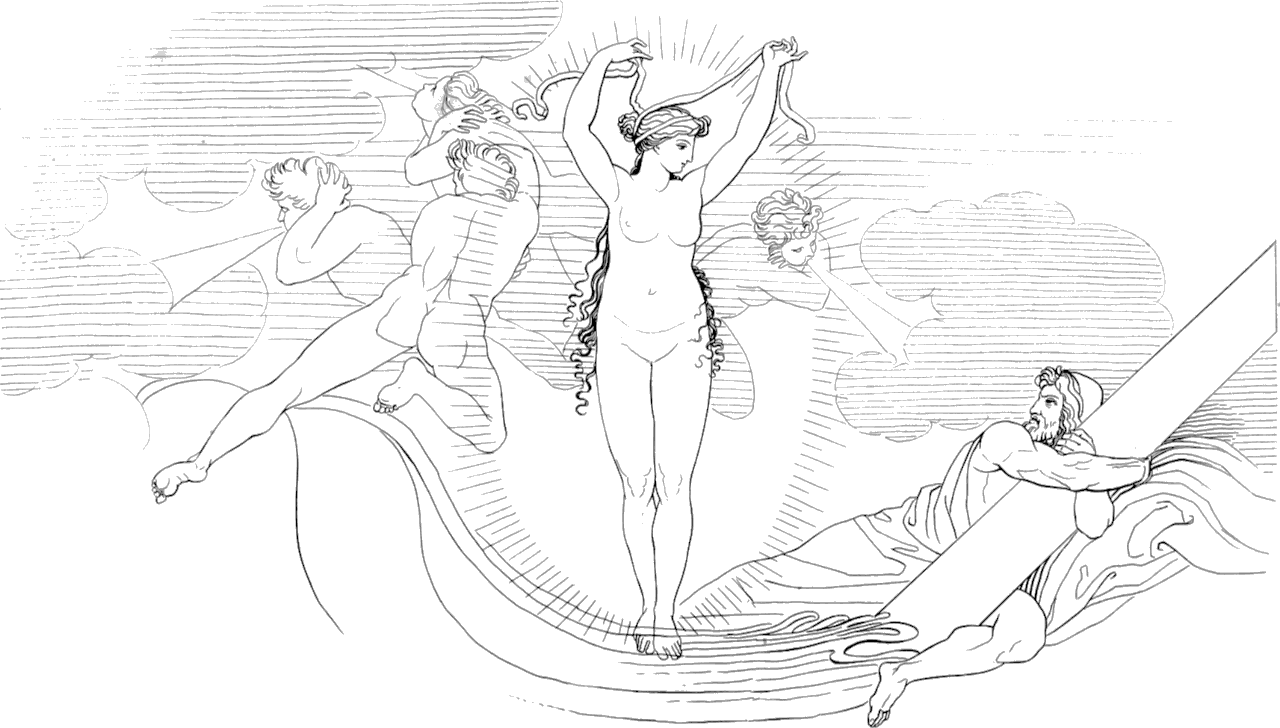

350ὣς ἄρα μιν εἰπόντ’ ἔλασεν μέγα κῦμα κατ’ ἄκρης

δεινὸν ἐπεσσύμενον, περὶ δὲ σχεδίην ἐλέλιξε.

τῆλε δ’ ἀπὸ σχεδίης αὐτὸς πέσε, πηδάλιον δὲ

ἐκ χειρῶν προέηκε: μέσον δέ οἱ ἱστὸν ἔαξεν

δεινὴ μισγομένων ἀνέμων ἐλθοῦσα θύελλα,

τηλοῦ δὲ σπεῖρον καὶ ἐπίκριον ἔμπεσε πόντῳ.

τὸν δ’ ἄρ’ ὑπόβρυχα θῆκε πολὺν χρόνον, οὐδ’ ἐδυνάσθη

αἶψα μάλ’ ἀνσχεθέειν μεγάλου ὑπὸ κύματος ὁρμῆς:

εἵματα γάρ ῥ’ ἐβάρυνε, τά οἱ πόρε δῖα Καλυψώ.

ὀψὲ δὲ δή ῥ’ ἀνέδυ, στόματος δ’ ἐξέπτυσεν ἅλμην

πικρήν, ἥ οἱ πολλὴ ἀπὸ κρατὸς κελάρυζεν.

ἀλλ’ οὐδ’ ὣς σχεδίης ἐπελήθετο, τειρόμενός περ,

ἀλλὰ μεθορμηθεὶς ἐνὶ κύμασιν ἐλλάβετ’ αὐτῆς,

ἐν μέσσῃ δὲ καθῖζε τέλος θανάτου ἀλεείνων.

τὴν δ’ ἐφόρει μέγα κῦμα κατὰ ῥόον ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα.

ὡς δ’ ὅτ’ ὀπωρινὸς Βορέης φορέῃσιν ἀκάνθας

ἂμ πεδίον, πυκιναὶ δὲ πρὸς ἀλλήλῃσιν ἔχονται,

ὣς τὴν ἂμ πέλαγος ἄνεμοι φέρον ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα:

ἄλλοτε μέν τε Νότος Βορέῃ προβάλεσκε φέρεσθαι,

ἄλλοτε δ’ αὖτ’ Εὖρος Ζεφύρῳ εἴξασκε διώκειν.

τὸν δὲ ἴδεν Κάδμου θυγάτηρ, καλλίσφυρος Ἰνώ,

Λευκοθέη, ἣ πρὶν μὲν ἔην βροτὸς αὐδήεσσα,

νῦν δ’ ἁλὸς ἐν πελάγεσσι θεῶν ἒξ ἔμμορε τιμῆς.

ἥ ῥ’ Ὀδυσῆ’ ἐλέησεν ἀλώμενον, ἄλγε’ ἔχοντα,

αἰθυίῃ δ’ ἐικυῖα ποτῇ ἀνεδύσετο λίμνης,

ἷζε δ’ ἐπὶ σχεδίης πολυδέσμου εἶπέ τε μῦθον:

κάμμορε, τίπτε τοι ὧδε Ποσειδάων ἐνοσίχθων

ὠδύσατ’ ἐκπάγλως, ὅτι τοι κακὰ πολλὰ φυτεύει;

οὐ μὲν δή σε καταφθίσει μάλα περ μενεαίνων.

ἀλλὰ μάλ’ ὧδ’ ἔρξαι, δοκέεις δέ μοι οὐκ ἀπινύσσειν:

εἵματα ταῦτ’ ἀποδὺς σχεδίην ἀνέμοισι φέρεσθαι

κάλλιπ’, ἀτὰρ χείρεσσι νέων ἐπιμαίεο νόστου

γαίης Φαιήκων, ὅθι τοι μοῖρ’ ἐστὶν ἀλύξαι.

τῆ δέ, τόδε κρήδεμνον ὑπὸ στέρνοιο τανύσσαι

ἄμβροτον: οὐδέ τί τοι παθέειν δέος οὐδ’ ἀπολέσθαι.

αὐτὰρ ἐπὴν χείρεσσιν ἐφάψεαι ἠπείροιο,

ἂψ ἀπολυσάμενος βαλέειν εἰς οἴνοπα πόντον

πολλὸν ἀπ’ ἠπείρου, αὐτὸς δ’ ἀπονόσφι τραπέσθαι.

ὣς ἄρα φωνήσασα θεὰ κρήδεμνον ἔδωκεν,

αὐτὴ δ’ ἂψ ἐς πόντον ἐδύσετο κυμαίνοντα

αἰθυίῃ ἐικυῖα: μέλαν δέ ἑ κῦμα κάλυψεν.As he was talking to himself, a frightfully great wave drove down

rushing over him, and his raft whirled around.

He was thrown far from the raft, the rudder

yanked from his hands; and the mast broke in half

from a terrible blast of the whirling winds,

the yard-arm and sail plunging deep into the sea.

A long time he was held under, and he wasn’t able

to very quickly rise from under the rush of the mighty wave

since the clothes which Kalupso gave him weighed him down.*

Finally, at length he surfaced, his mouth spitting out bitter brine

which ran in many streams from his crown.

He didn’t forget the raft in spite of his distress,

but rushed after it in the waves and held it to himself,

and he sat in the middle to hide from a deadly end,

as the great wave carried it here and there in the current.

Just like how, in late summer, Boreas* carries thistledown

along the plain, and clusters cling to each other,

in the same way the winds carried the raft here and there in the sea:

at once Notos* tossing it to Boreas to carry,

and again Euros* giving it up for Zephuros* to chase.

And then came the daughter of Kadmos, dainty-footed Ino,*

the White Goddess, who used to be a mortal possessed of voice,*

but now, in the sea, receives her share of reverence given to its gods.

She pitied Odusseus in his wandering and the suffering he bore,

and she rose from the water like a seabird in flight,

alighted upon the raft of many fastenings, and said to him:

“You poor thing, why is Poseidaon Earth-Shaker so

very mad* at you, that he causes you so much trouble?

Well, he won’t kill you even though he really wants to.

But you seem sensible enough to me, so do as I say:

take off your clothes and abandon your raft to be borne by the winds,

but, swimming with your hands, try to get to

the land of the Phaiëkians, where it is your fate to escape.

And here, wrap my immortal veil* around your chest,

so that you may fear neither suffering nor death;

but when you’ve laid hands on the firm ground,

untie it and throw it back into the wine-like sea*

far from land, and turn yourself far away from it.”

So speaking, the goddess gave him her veil,

and dove back into the surging sea

like a bird, and the dark swell covered her.

- The clothes which Kalupso gave him weighed him down: if Odusseus is the soul, and Kalupso (“one who covers”) is Earth, then the clothes she gives him must be the physical body. Focusing on the body, of course, hampers the soul which wishes to return home.

- Boreas: the frigid north wind.

- Notos: the desiccating south wind.

- Euros: the wet east wind.

- Zephuros: the balmy west wind.

- Ino: Ino (from νέω “I swim,” cf. Tzetzes, on Lukophron §107) is the daugher of Kadmos, sister of Semele, and aunt and nurse of Dionusos.

- Possessed of voice: humans communicate to the ears with words, but gods communicate directly to the mind with concepts, a thing which is at once uncanny and completely natural when one experiences it.

- So very mad: this is a joke on Odusseus’s name, which means “he is angry with.”

- Veil: literally κρήδεμνον “head-tie,” which could presumably refer to any kind of head-scarf or hair-ribbon, but Penelopeia wears one for modesty in the presence of men, so it most likely means a veil.

- Wine-like sea: οἴνοπα πόντον, literally “wine-faced sea” and usually taken as “dark in color,” but the sea is a reference to life in the material world, which is as intoxicating and disorienting to the soul as wine is to the body.

(Homeros, Odusseia V 313–53, as translated—hopefully not too badly!—by yours truly.)

There is a lot of overlap between the Mysteries and the Epic Cycle:

| # | Epic Cycle | Horos | Orestes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kupria | Seth holds a feast. | The wedding of Peleus and Thetis. |

| 2 | Kupria | Seth kills Osiris, seals him in a box, and drops the box in the Nile. | The judgement of Paris. |

| 3 | Kupria | The box lands at Bublos. A heather stalk grows around the box. Malkander takes the heather stalk into his house. | The rape of Helene. |

| 4 | Kupria | Isis wanders. Nephthus exposes Anoubis. Isis finds Anoubis and takes him as her attendant. | Gathering of the armies. Agamemnon sacrifices Iphegenia, but Artemis replaces her with a deer, makes her immortal, and takes her as her attendant. |

| 5 | Isis tracks Osiris to Bublos, sits by a spring, and weeps. Astarte invites her into her house. | [cf. 10] | |

| 6 | Kupria | Isis kills Astarte’s youngest son. | Failed first war on Troia. Troilos dies. |

| 7 | Ilias | Isis takes Diktus as her attendant. | Akhilleus commits to dying at Troia. |

| 8 | Isis recovers Osiris. | [cf. 11] | |

| 9 | Aithopis | Isis kills Diktus for his curiosity. | Paris kills Akhilleus. |

| 10 | Ilias Mikra | [cf. 5] | Troian horse. |

| 11 | Iliou Persis | [cf. 8] | Troia sacked. Menelaos recovers Helene. |

| 12 | Nostoi | Isis returns to Egypt. Seth divides Osiris into fourteen pieces. A fish eats the penis. Isis recovers the pieces and reassembles Osiris. | The Akhaians are scattered but eventually return home, except Aias (who dies at sea), Menelaos and Odusseus (who are lost at sea), and Agamemnon (who is assassinated by Aigisthos and Klutaimnestra). |

| 13 | Odusseia | Isis draws Osiris’s essence from his corpse and gives birth to Horos. When Horos grows up, Osiris trains him from Duat. Horos beheads Isis, is judged by the gods, defeats Seth, and becomes king. | Orestes flees into exile. When Orestes grows up, the Puthia tells him to avenge his father. Orestes kills Aigisthos and Klutaimnestra, is chased by the Erinues, is judged by Athena, and becomes king. |

(I have omitted the Telegoneia as it concerns Odusseus and not Orestes, who is a different hero.)

If my associations are correct, then Osiris=Helene, Isis=the Akhaian host (e.g. those oathbound to Menelaos, notably not including Akhilleus who was too young to woo Helene), Seth=Eris, Anoubis=Iphegenia, Bublos=Troia, Astarte’s unnamed son=Troilos (and the first Troian war generally), Diktus=Akhilleus (and the second Troian war generally), Horos=Orestes, Osiris as a jackal=the Puthia, Seth as a red bull=Aigisthos, the council of gods=the Athenian jury.

The only difficulty, really, is that it is Osiris that is divided up upon his return to Egypt and not Isis, whereas it is the Akhaians who are divided up on their return to Akhaia (and not Helene). This is a really significant symbolic difference and is necessary for the two narratives to work. From the pattern in the myth, Agamemnon should presumably have to be Osiris’s penis, which I guess shouldn’t be too surprising, since anybody who’s read the Ilias can tell you he’s a dick.

Despite that problem, though, the stories are so close there must be something to it. I still don’t have a convincing thesis for what’s going on here; I’m presently wondering if the version of the Horos-myth we have is, in fact, late and Syrian (presumably the oldest versions of the Horos-myth don’t involve Bublos)—in which case it could have been influenced from both sides of the Mediterranean. I’m going to need to go over the Pyramid Texts with more care, I think...

Wepwawet is onomatopoeia for the wild dog’s cry, the well-known coyote’s cry at the rising of the moon. But in keeping with the tendency of hieroglyphs to contain layes of deeper meaning, this word is not simply a name. It is a verbal phrase. The hieroglyphic name (𓄋𓈐𓈐𓈐) is spelled with a pair of horns, wp (to open), followed by wat (path) in the plural, wawat: three pictures of the sign for path. Hence the action is implicit in the thing, the verb is hidden in the noun: the dog, conjured by the sound of its name, does something—it is the opener of paths. The dog embodies a primary Egyptian concept, what we have come to call evil. The wild dog is a very dangerous animal. Yet the dog has a dual nature. It is its own twin: it is wild but can be tamed. Hence, the wild dog is not a bad thing; it is, after all, a dog, the ultimate tracker, the animal that finds the path. The dog appears in the text as a gradual elaboration of this idea. It appears as Anubis (𓃢), the wild dog tamed, ears back, tail down, black like the night, where it shows you how to find the way. Next the dog appears as Set (𓃩), with ears up and raised tail forked like lightning, ready to kill. Set is the universal embodiment of the wilderness, the wolf. This form of the dog means danger. [...] The dog embodies the purest love and the greatest danger, the mystery of good and bad in one.

(Susan Brind Morrow, The Dawning Moon of the Mind I ii.)

This links up to my thought that Anoubis is karma: a dog can be wild, which hungrily chases one and tears them to pieces (cf. Aktaion), or it can be tamed, devotedly following one and supporting them (cf. Anoubis weighing the heart).

It is also a support of my theory that Plotinos is a wepwawet (woof woof)...

Susan Brind Morrow says, in her study of the Pyramid Texts, that Horus and Anoubis are meant to refer to the two brightest stars in the sky, Sirius and Canopus, respectively. (And, of course, spiritual principles derived from these.) Indeed, she says that the word Canopus (Κάνωβος) is derived from Anoubis (Ἄνουβις), which is at least plausible to me; in Greek, they sound almost the same.

This is interesting since it ties into my interpretation of the Troia myth, where Helene is Osiris and Menelaus is Isis. See, Canopus is named after the pilot of Menelaus’s flagship; when Menelaus returned from Troia, he was marooned for a long time in Egypt, and Canopus died there (and the Egyptian city of Canopus, built where he supposedly died, was named for him, cf. Strabon, Geography XVII i §17).

But Isis was also famously known for her boat—the festival of Navigium Isidis, one of the primary festivals in Rome, was all about this—in which she traveled with Anoubis, her bodyguard and attendant, while searching for the pieces of Osiris. This occurs at the same time in both myths (point 12, above).

The star Canopus, it should be noted, is the brightest star of the constellation Argo Navis, which is a ship. According to Plutarch, the Egyptians called it Osiris’s boat (Isis and Osiris XXII), but he also says that Orion is sacred to Horos and Sirius to Isis; but if Morrow is correct in her translation, then it’s clear Plutarch permuted the associations: the ship should be Isis’s; Orion, Osiris’s; and Sirius, Horos’s.

Well, shit. I think I finally figured it out.

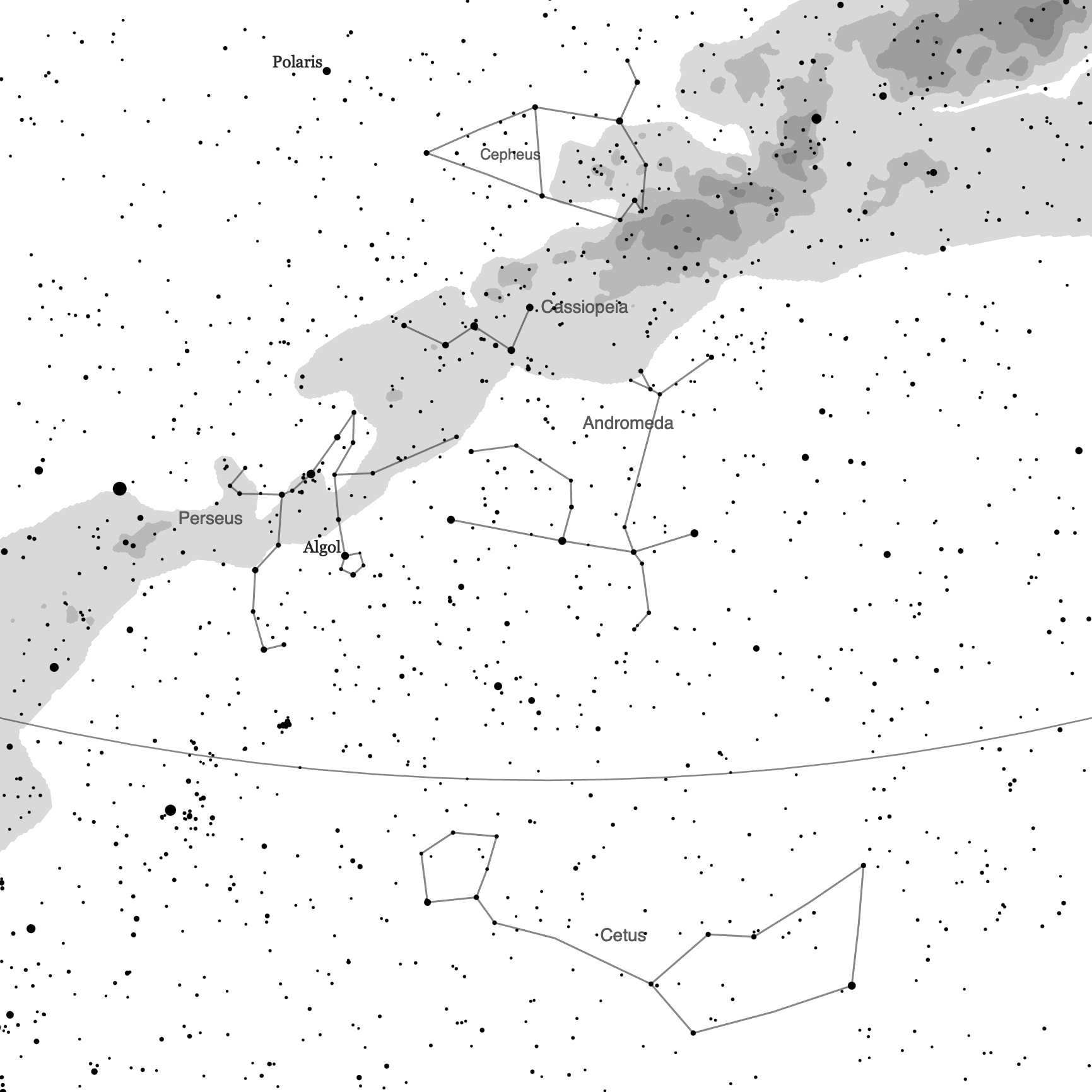

It’s well-known that the myth of Perseus is illustrated in the night sky:

There’s Perseus holding Medousa’s head (the demon star Algol from Arabic ra’s al-ghul “head of the ogre”), rushing to save Andromeda, chained to a rock, from the sea monster Ketus (the ecliptic nicely acting as the surface of the sea), while Kepheus and Kassiopeia look on.

This is often said to be the only complete mytheme still illustrated in the constellations as we know them today, but I just realized that this is mistaken: there’s another one, right next to it:

Nut is the sky. Geb is the earth, and his penis is the axis the earth turns around. Their children are the constellations, and Ra prevents her from giving birth because the Sun hides the constellations from view: we can only see them at night. Osiris is the one we call Orion, the great man in the sky, and the shape of Orion is, I presume, the reason why the Egyptians drew figures in their peculiar profile. The Nile is the Milky Way, of course, and there we see Isis in her boat, which we call by its Greek name, the Argo, still sailing the Nile searching for her husband. Osiris’s penis is highlighted in the myth because it’s the most notable feature of his constellation, though we call it Orion’s sword. (Perhaps this is a euphemism, though; in Greek, the word for sword, ἄορ, literally means “hanging thing.”) Next to Osiris, we see the Apis bull, though we call it by its Latin name, Taurus. The children of the constellations are, of course, the stars: Horos is Sirius, the brightest star of heaven, literally following in his father’s footsteps; while Anoubis is Canopus, the second-brightest, attending to Isis in her boat.

Thus the theogony, as I said, is exoteric because everyone can look up at the sky and see the constellations; but the Mysteries are esoteric because only the initiated can look up at the sky and understand what the constellations mean.

τὸν δ’ αὖτε

And then to him προσέειπε περίφρων Πηνελόπεια:

circumspect Penelopeia said,

ξεῖν’,

Stranger, ἦ τοι μὲν

I tell you true, ὄνειροι

dreams ἀμήχανοι ἀκριτόμυθοι

wayward and mysterious

γίγνοντ’,

are born, οὐδέ τι πάντα τελείεται

and they don’t all come true ἀνθρώποισι.

to men,

δοιαὶ γάρ τε

for twofold πύλαι ἀμενηνῶν εἰσὶν ὀνείρων:

are the gates of evanescant dreams:

αἱ μὲν γὰρ

one κεράεσσι τετεύχαται,

is made of horn αἱ δ’

and the other ἐλέφαντι:

of ivory.

τῶν οἳ μέν

Those of which κ’ ἔλθωσι

should come διὰ πριστοῦ ἐλέφαντος,

through the carved ivory,

οἵ ῥ’ ἐλεφαίρονται,

those are wily,* ἔπε’ ἀκράαντα φέροντες:

carrying false messages;

οἱ δὲ

but those διὰ ξεστῶν κεράων ἔλθωσι θύραζε,

that come through the door of polished horn,

οἵ ῥ’ ἔτυμα κραίνουσι,

those come true* βροτῶν ὅτε κέν τις ἴδηται.

whenever some mortal should see them.

ἀλλ’

but ἐμοὶ οὐκ ἐντεῦθεν ὀΐομαι

I doubt, from there to me, αἰνὸν ὄνειρον

that weird dream

ἐλθέμεν:

came; ἦ κ’ ἀσπαστὸν

it would truly be welcome ἐμοὶ

to me καὶ

and παιδὶ γένοιτο.

my child.

- wily: ἐλεφαίρονται is a pun on ἐλέφαντι “made of ivory.”

- come true: κραίνουσι is a pun on κεράεσσι “made of horn.”

(Homeros, Odusseia XIX 559–69.)

Something in the air of late—may your dreams issue through the gate of horn...

A confirmation of my guess that Iphegenia=Anoubis comes from Hesiod’s Catalogue of Women (fr. 19, tr. Glenn Most):

Because of her beauty Agamemnon, lord of men, married

Tyndareus’ daughter, dark-eyed Clytemestra;

she bore beautiful-ankled Iphimede in the halls

and Electra who contended in beauty with the immortal goddesses.

The well-greaved Achaeans sacrificed Iphimede

on the altar of golden-spindled noisy Artemis

on the day when they were sailing on boats to Troy

to wreak vengeance for the beautiful-ankled Argive woman—

a phantom: herself, the deer-shooting Arrow-shooter

had very easily saved, and lovely ambrosia

she dripped onto her head, so that her flesh would be steadfast forever,

and she made her immortal and ageless all her days.

Now the tribes of human beings on the earth call her

Artemis by the Road, temple-servant of the glorious Arrow-shooter.

As the last one in the halls, dark-eyed Clytemestra,

overpowered by Agamemnon, bore godly Orestes,

who when he reached puberty took vengeance on his

fathers murderer, and he killed his own man-destroying mother with the

pitiless bronze.

Artemis by the Road is Hekate, and Hekate is the exact equivalent of Anoubis in the Demeter myth. The sacrifice on the altar surely mirrors the exposure of Anoubis as an infant.

ἡδὺ δὲ

and sweet, καὶ

too, τὸ πυθέσθαι,

it is to learn ὅσα

the kinds of things θνητοῖσιν ἔνειμαν

assigned to mortals

ἀθάνατοι,

by the immortals, δειλῶν

base τε καὶ

and ἐσθλῶν

noble τέμαρ ἐναργές

clearly distinguished

(Hesiodos, Melampodia, as quoted by Clement of Alexandria.)