All of the entries on this page are collected from my Dreamwidth blog.

I chanced across Lafcadio Hearn's In Ghostly Japan the other day. I've been enjoying its mix of travelogue, topical studies, and ghost stories—but what I wanted to call out here is this pleasant meditation analogizing the evolution of the domesticated silkworm moth to the evolution of the soul.

It is a good reminder that while the goal is, in a sense, to leave material existence behind; doing so does not escape us from our troubles, but rather prepares us for their intensification.

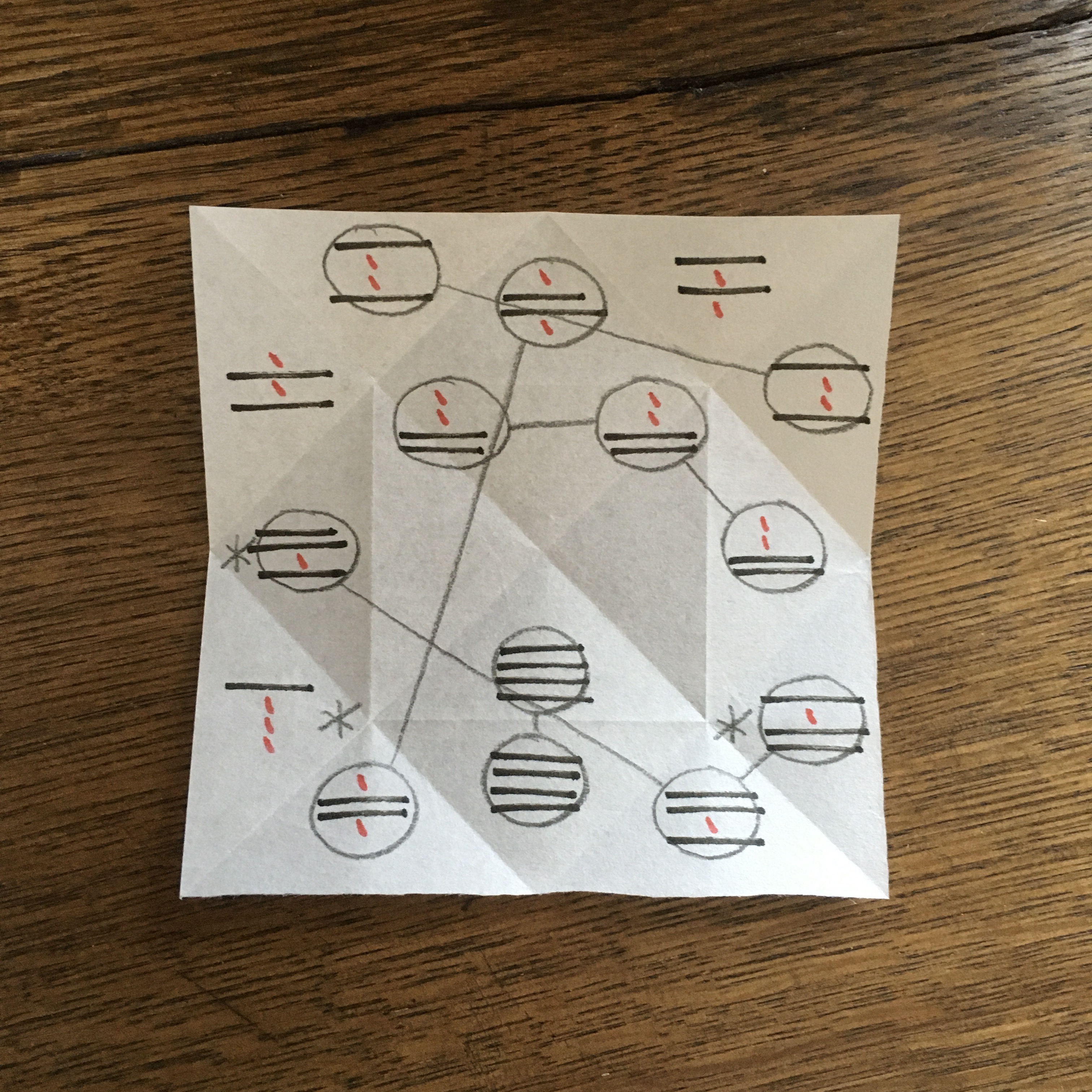

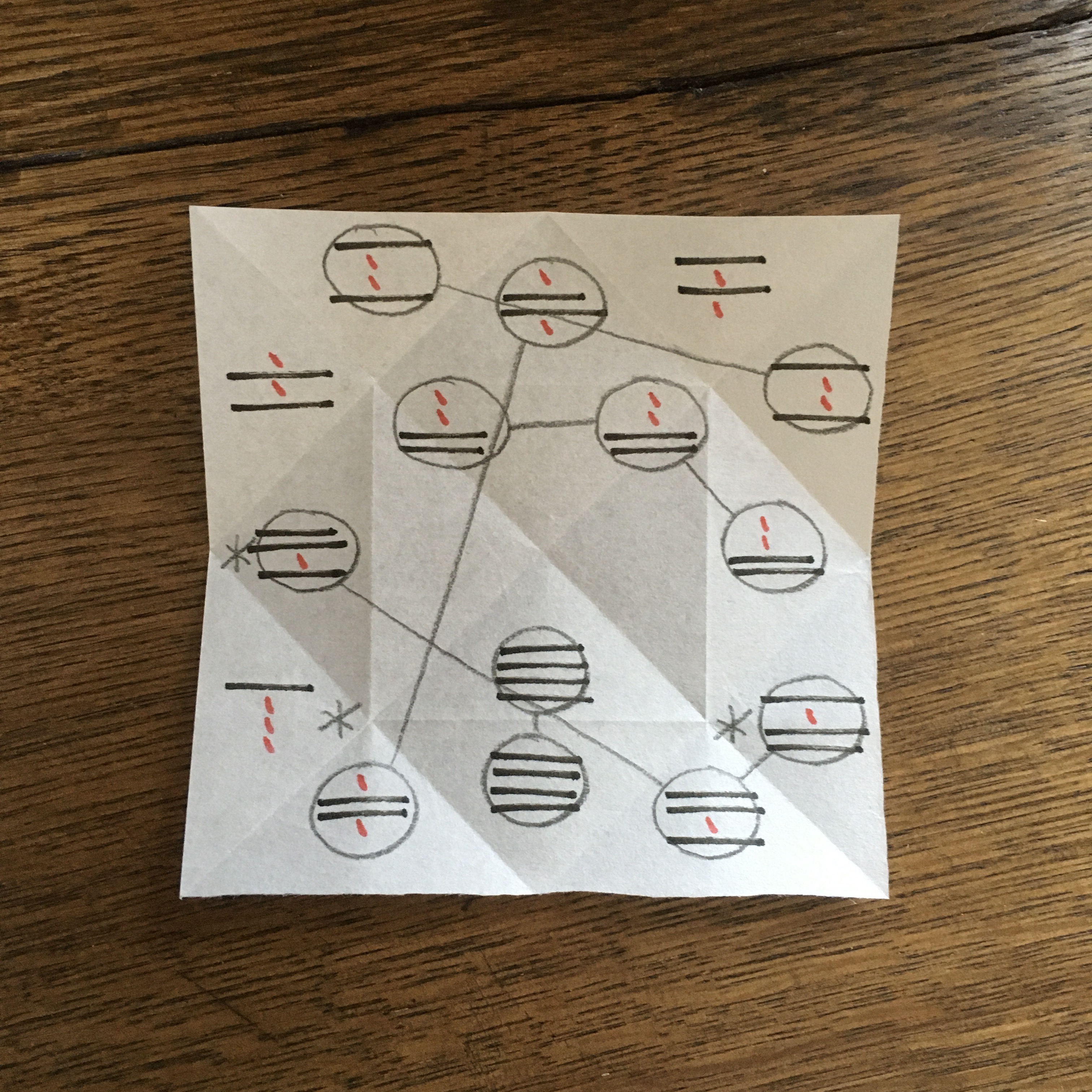

For a couple years now, I have written my daily, monthly, and yearly geomancy readings on little squares of paper which have been folded to demarcate the houses:

When my family left New York in a hurry last year, I destroyed all of the squares I had and switched to writing my readings in a diary; but once we moved in to our new house, I resumed folding my squares. I'm not really much for ritual, but I have long been fond of origami and I find the process of cutting and folding paper relaxing.

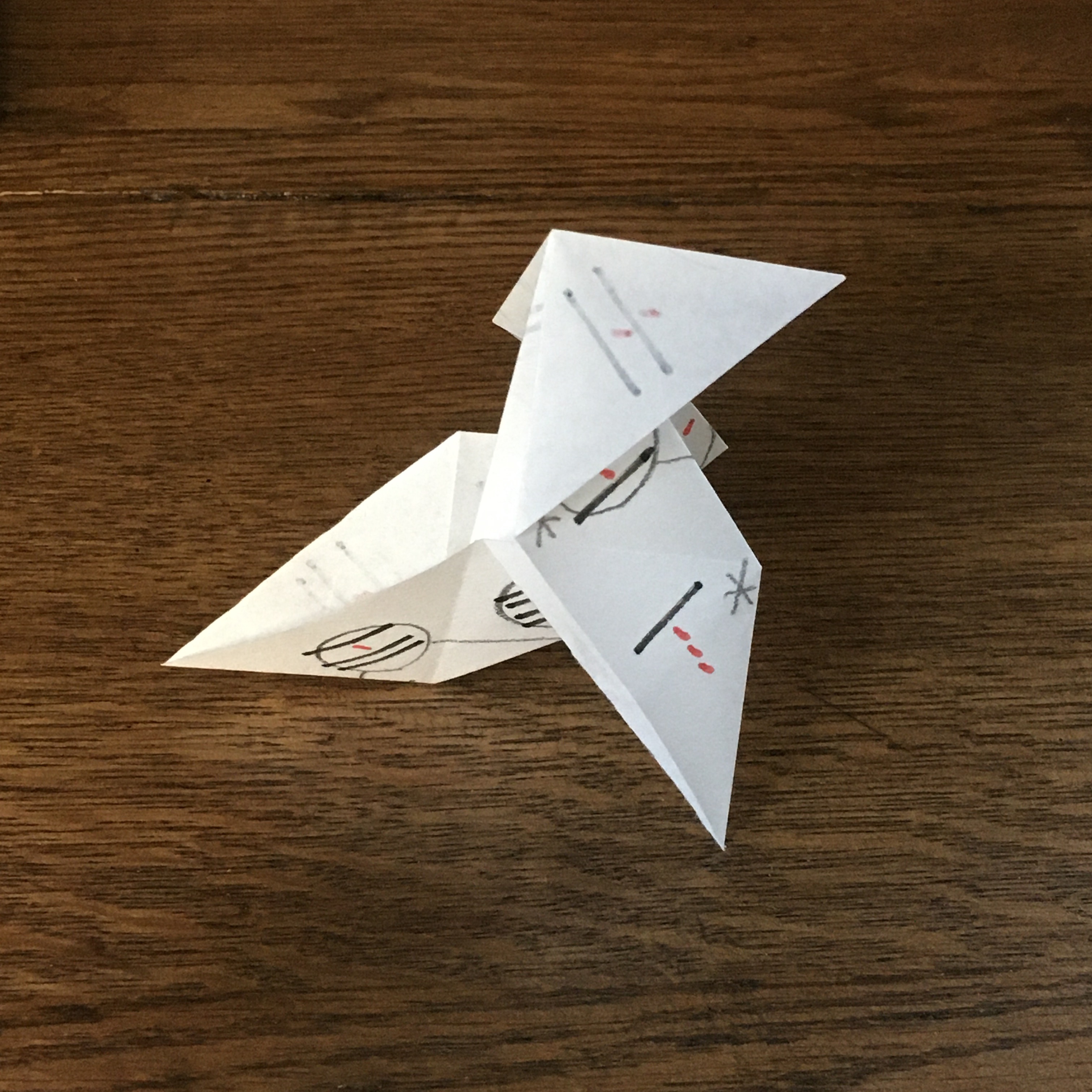

I realized, not so long ago, that the crease pattern in the paper is exactly that used for a traditional origami model—it doesn't have a widespread name in English, but in Spanish it is called a pajarita ("little bird") and in French it is called a cocotte ("hen"). (Personally, I think it looks like a sphinx, but my daughter says with a shrug, "It looks like a bird to me, daddy.")

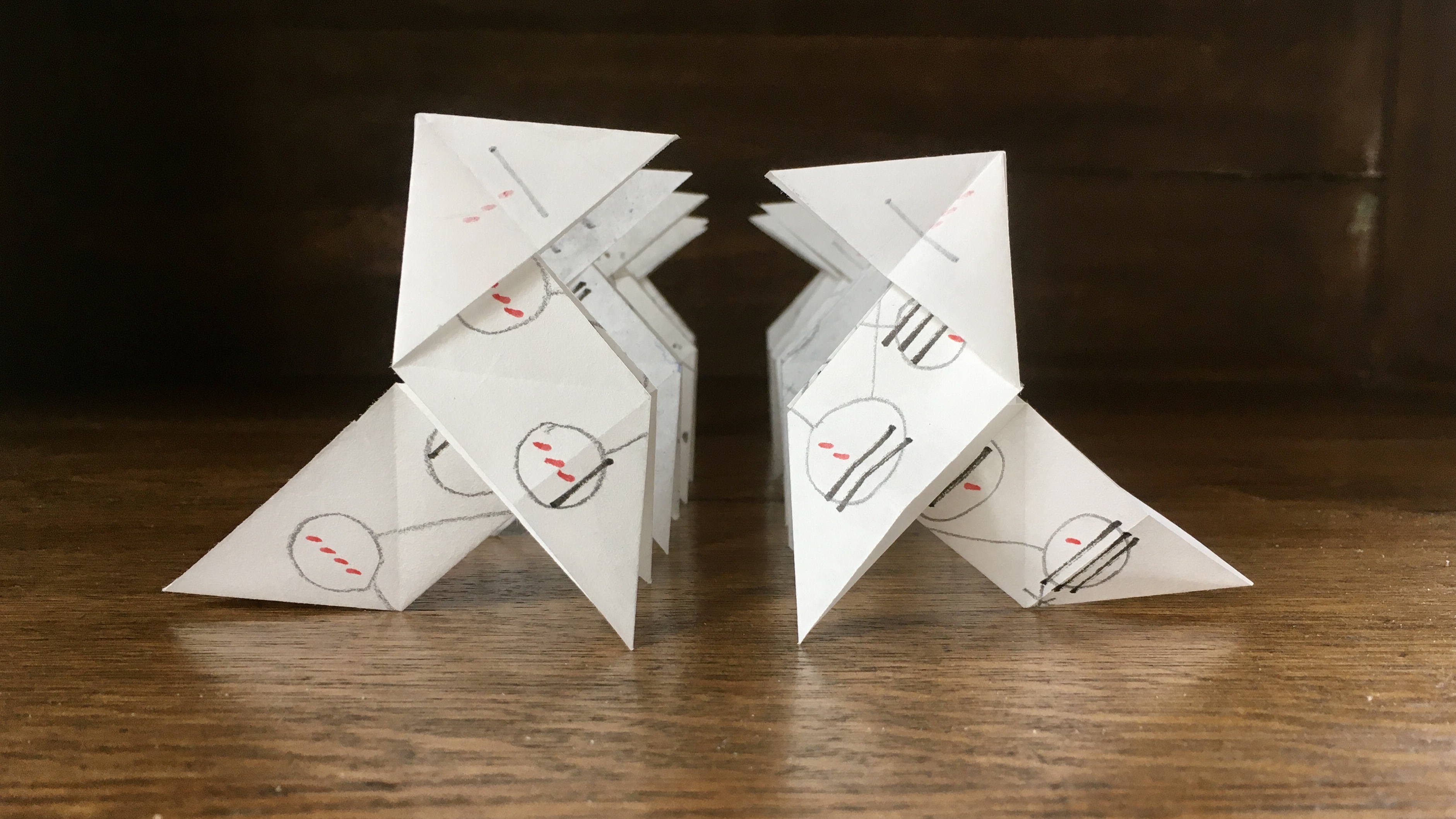

Because the crease pattern is the same, the readings naturally want to fold themselves into little birds, so recently I've been letting them. I tend to keep my yearly, monthly, and daily readings upon the altar in my office and return often to meditate upon them... for some reason, the readings seem to have more of a personality when they're bird-shaped.

This week, I went through the stack I've been accruing all year and folded them all up. I've got a few hundred of them now, in all sorts of colors: a little avian army—air force?—carrying a year's dreams and experiences, crystallized.

I was curious, so I went looking, and it turns out there may be something to how my geomancy readings want to become birds; I found this on the British Origami Society's website:

The paper pajarita falls into the class of traditional folds based on what we now know as the "Windmill base". [...]

Vicente Palacios has suggested that there may be some connection between the Windmill base and the Astrological Square, because the crease pattern of the windmill base is the same as that of the Astrological Square, which commonly formed the basic pattern of horoscopes from the 12th century to the 18th century. It is suggested that the pattern was introduced by the scholar Gerardo Cremone at Toledo in the 12th Century. The connection between the astrological square and the windmill base has not been proved, although there are arguments for thinking that there may well be something in the hypothesis. If the theory it is true, it is likely that the pattern of the astrological square derived from the windmill base and not vice versa.

Folded paper Baptismal Certificates were commonly used in central Europe in the 17th and 18th Centuries and bore particulars of the child's birth and date of baptism together with various pious verses. They were actually folded in a double blintz or windmill pattern. Alternatively, they might be folded from a square folded into nine smaller squares in the manner of the puzzle purse. While there is no evidence to show that folded baptismal certificates were derived from the square horoscopes it is suggested that the baptismal certificates were a Christianised version of them and that the horoscopes, too, were originally folded. However, no folded horoscope has yet been found.

Fold gently.

Crease firmly.

When I first came to Japan, the dominant colors of male costume were dark[. ...] Women's costumes are of course more varied; but the character of the fashions for adults of either sex indicates no tendency to abandon the rules of severe good taste;—gay colors appearing only in the attire of children and of dancing-girls, to whom are granted the privileges of perpetual youth.

(Lafcadio Hearn, Gleanings in Buddha-Fields.)

It is sad, I think, that the scheme of planetary joys fell out of use in Western Astrology, as it appears to me a crucial thread tying the philosophy into a unified whole. And here, we see illustrated it so elegantly! Of course dancing-girls are given the privileges of youth, since children, dancing, and pleasing attire are all fifth-house endeavors, in which Venus rejoices.

Before digging into a work, I like to know a little about where the author is coming from. My book on Plotinus has an adequate little biography of him (an abridgment of Porphyry's), but of MacKenna, the translator, nothing is; what one finds of him, looking online, is a mystery. Not in that he is obscure, but in that he is a thread that, being tugged, draws you down the rabbit-hole into a still-greater mystery, one which enchants and bewitches and entices and maddens. That is all to say, MacKenna seems to have been very interesting!

So to attempt to get a sense of the man, I turn to his published letters and diary, and clicking around randomly—ha!—brought me to a letter from MacKenna to Sir Ernest Debenham, penned in January of 1916 (and hastily transcribed by me, so I apologize for any errors):

I hope you and yours are well and as happy as the dismal times allow: myself I sicken at the all the blood, the mowing down of the youth of Europe, the stop, dead, of all we have thought of civilization, the multiform, wide as the world almost, agony and desolation. Plotinus mocks at all such emotions—if I weren't too lazy I'd transcribe a passage ad hoc, very fine as literature but dreadfully unreal to-day, at least to my lower sense—and this tho' Plotinus had been a soldier and seen, ce qu'on appelle vu ["what we call seen"], on no small scale too, the horrors of which his "Sage"—really our "Saint" tho' one daren't use the word— declares a trivial ragged fringe on his beautiful inner peace. For my part I find this war, with all that it entails to the world and to my own poor little land, setting me blaspheming. I see men as trees walking—soulless motion merely, and no purpose over it all—perhaps beasts ravening would be better, nearer to my mind, and no thought ruling the rage even to some sound material end. I suppose in the light of history all this is absurd—and then Plotinus would be right—all comes out smiling at the end, and the fall of one civilization is the beginning of another: if the Yellow Peril that once was a music-hall joke turned into a Yellow Actuality and all the world was yellow, there would once be once more arts and religions and contempt for the ancient and passed thing with lyric celebrations of the triumph of light at last. The world certainly renews itself, and always manages, with relatively brief periods of disaster and ugliness, to keep a sober average—but at the moments of ugliness, it is no pretty thing, no cheerful sight, and we get a sharp reminder (which our history is generally too dead in our minds to give us) that all our "truths" are merely dreams and that nothing is sure but birth and death, both sure but dark in their meaning. The God of the world is discovered to be an incalculable: we do not know what he is up to, or whether there is any care up there at all: ["but he is impious"], says Æschylus of the man that thinks this, that Gods do not deign to care for the good and ill doings of men: I'm afraid I'm ["impious"]. Of course, by the way, so is Plotinus in this: his Supreme is too great and different to care: it is man that must care; and on that Plotinus gets as stern a moral code as others get out of the God who is offended and appeased and always working at the wheel of the world. The Father's house has many mansions and still more approaches: all roads lead to its peace, and a good Plotinian would be undistinguished in life from a good Christian, except perhaps being better.

I imagine we will, ourselves, be in the same times MacKenna lamented quite soon! But the dance of Mars gives way to the dance of Venus, just as the dance of Venus gives way to the dance of Mars. If we embrace the show of Venus in all Her beauty and grace and joy and voluptuousness, should we not, too, embrace the show of Mars? Sure, it may be dirty and hard and sorrowful and severe, but ah! what He brings with Him!

I am reminded of a Sufi parable:

A dervish fell into the Tigris. Seeing that he could not swim, a man on the bank cried out, "Shall I tell some one to bring you ashore?" "No," said the dervish. "Then do you wish to be drowned?" "No." "What, then, do you wish?" The dervish replied, "God's will be done! What have I to do with wishing?"

Perhaps we each have our favorite Divinity, but nonetheless may we all learn and learn well to trust all Divinity, and in so doing learn to appreciate every dance.

Mnesarchos the Samian was in Delphi on a business trip, with his wife, who was already pregnant but did not know it. He consulted the Pythia about his voyage to Syria. The oracle replied that his voyage would be most satisfying and profitable, and that his wife was already pregnant and would give birth to a child surpassing all others in beauty and wisdom, who would be of the greatest benefit to the human race in all aspects of life. Mnesarchos reckoned that the god would not have told him, unasked, about a child, unless there was indeed to be some exceptional and god-given superiority in him. So he promptly changed his wife's name from Parthenis to Pythais, because of the birth and the prophetess. When she gave birth, at Sidon in Phœnicia, he called his son Pythagoras ["Pythia speaks"], because the child had been foretold by the Pythia.

(Iamblichus on the Pythagorean Life, as translated by Gillian Clark.)

Well, Chærephon, as you know, was very impetuous in all his doings, and he went to Delphi and boldly asked the oracle to tell him whether [...] there was anyone wiser than I was, and the Pythian prophetess answered that there was no man wiser. [...]

When I heard the answer, I said to myself, "What can the god mean? and what is the interpretation of this riddle? for I know that I have no wisdom, small or great. What can he mean when he says that I am the wisest of men? And yet he is a god and cannot lie; that would be against his nature." [...]

The truth is [...] that God only is wise; and in this oracle he means to say that the wisdom of men is little or nothing; he is not speaking of Socrates, he is only using my name as an illustration, as if he said, "He [...] is the wisest, who, like Socrates, knows that his wisdom is in truth worth nothing."

(Socrates, as quoted by Plato, and as translated by Benjamin Jowett.)

Apollo was consulted by Amelius, who desired to learn where Plotinus' soul had gone. [...]

Pure spirit—once a man—pure spirits now

Greet thee rejoicing, and of these art thou;

Not vainly was thy whole soul always bent

With one same battle and one the same intent

Through eddying cloud and earth's bewildering roar

To win her bright way to that stainless shore.

Ay, 'mid the salt spume of this troublous sea,

This death in life, this sick perplexity,

Oft on thy struggle through the obscure unrest

A revelation opened from the Blest—

Showed close at hand the goal thy hope would win,

Heaven's kingdom round thee and thy God within.

So sure a help the eternal Guardians gave,

From life's confusion so were strong to save,

Upheld thy wandering steps that sought the day

And set them steadfast on the heavenly way.

Nor quite even here on thy broad brows was shed

The sleep which shrouds the living, who are dead;

Once by God's grace was from thine eyes unfurled

This veil that screens the immense and whirling world,

Once, while the spheres around thee in music ran,

Was very Beauty manifest to man;—

Ah, once to have seen her, once to have known her there,

For speech too sweet, for earth too heavenly fair!

But now the tomb where long thy soul had lain

Bursts, and thy tabernacle is rent in twain;

Now from about thee, in thy new home above,

Has perished all but life, and all but love,—

And on all lives and on all loves outpoured

Free grace and full, a spirit from the Lord,

High in that heaven whose windless vaults enfold

Just men made perfect, and an age all gold.

Thine own Pythagoras is with thee there,

And sacred Plato in that sacred air,

And whose followed, and all high hearts that knew

In death's despite what deathless Love can do.

To God's right hand they have scaled the starry way—

Pure spirits these, thy spirit pure as they.

Ah, saint! how many and many an anguish past,

To how fair haven art thou come at last!

On thy meek head what Powers their blessing pour,

Filled full with life, and rich for evermore!

(Porphyry, Life of Plotinus §22, as translated by Frederick William Henry Myers. Additional translations are also available from Thomas Taylor (verse), Dr. Henry More (verse), and Stephen MacKenna (prose).)

[Julian] sent Oribasius, physician and quæstor, to rebuild the temple of Apollo at Delphi. Arriving there and taking the task in hand, he received an oracle from the daimon:

Tell the emperor that the Daidalic hall has fallen.

No longer does Phœbus have his chamber, nor mantic laurel,

Nor prophetic spring, and the speaking water has been silenced.

(George Kedrenos, as translated by Timothy E. Gregory.)

I continue to make slow progress through Plotinus, but this morning I read an interesting paragraph indeed:

In the Supreme there is Reality because all things are one; ours is the sphere of images whose separation produces grades of difference. Thus in the spermatic unity all the human members are present undistinguishably; there is no separation of head and hand: their distinct existence begins in the life here, whose content is image, not Authentic Existence.

That is to say, here in the misty world of images, our various parts and capacities are seen distinctly, but in the higher realm, they blend together into a union.

I am reminded of two things.

First, it is commonly reported among those who experience Near-Death Experiences a lack of distinction of parts—they can see and touch and so on, but they don't experience having eyes or hands. To quote Raymond Moody's Life After Life: Despite it's lack of perceptibility to people in physical bodies, all who have experienced it are in agreement that the spiritual body is nonetheless something, impossible to describe though it may be. [...] Words and phrases which have been used by various subjects include a mist, a cloud, smoke-like, vapor, transparent, a cloud of colors, wispy, an energy pattern, and others which express similar meanings.

He quotes several people describing their experiences: My being had no physical characteristics, but I have to describe it with physical terms. I could describe it in so many ways, in so many words, but none of them would be exactly right. It's so hard to describe.

or [When I came out of the physical body] it was like I did come out of my body and go into something else. I didn't think I was just nothing. It was another body... but not another regular human body. Its a little bit different. It was not exactly like a human body, but it wasn't any big glob of matter, either. It had form to it, but no colors. And I know I still had something you could call hands. I can't describe it.

or It was like I was just there—an energy, maybe, sort of like just a little ball of energy.

Secondly, years ago, I asked my deity about whether I should consider Them a god or goddess, and They said to me, "It's complicated: it is more like both, though not like the kind of 'both' in your world [e.g. hermaphroditism]." Plotinus here is hinting at why: the very distinction of male and female fades, and you are left instead with unified capacity.

I'm reading Enneads III i, and came across this amusing paragraph:

[Let us suppose the universe is strictly material, being entirely composed by atoms.] These atoms are to move, one downwards—admitting a down and an up—another slant-wise, all at haphazard, in a confused conflict. Nothing here is orderly; order has not come into being, though the outcome, this Universe, when it achieves existence, is all order; and thus prediction and divination are utterly impossible, whether by the laws of the science—what science can operate where there is no order?—or by divine possession and inspiration, which no less require that the future be something regulated.

On the one hand, here is Plotinus anticipating Edward Lorenz by nearly two millennia.

But on the other, can you imagine any modern physicist using "divination appears to work in practice" as an axiom!?

Porphyry wrote in his Sentences:

7. [The] soul is bound down to the body by adverting to the passions arising from it, and it is loosed again by impassivity to it.

8. What Nature has bound, Nature also looses; and what the soul has bound, that it also looses. Now Nature bound the body in the soul; but the soul bound itself in the body. Nature, accordingly, looses the body from the soul; but the soul looses itself from the body.

9. Death, therefore, is twofold, that which is generally recognized, when the body separates from the soul; and that of the philosophers, when the soul separates from the body. And the one does not at all follow the other.

Recall that the soul moves in circles. This is because it has desire for something, and thus orbits it.

But what does it orbit? Mortal souls orbit the earth (or something itself within the earth's orbit). When one dies, where they go depends on what their soul desires: and if it desires the things of earth, the soul will simply circle back to the earth and begin a new revolution around it. And so most souls cycle back and forth between the world (life) and the underworld (death), around and around.

But if, when one dies, a soul desires something else, it will instead move to orbit that other thing. This is the basis of classical philosophy: to train a soul to desire something else, to move within the gravity well of that something else, so as to no longer be bound by the gravity of earth. This is the upward ascent of a soul from the world (life) through the aitherial (the process of training: philosophy, love, theurgy, etc.) to the empyrean (afterlife).

There are several associations that jump out at me regarding all this.

What Porphyry means when he says there are two deaths is: if the body slips from the soul, the soul's desire is presumably in the same place, and it returns in a new body. (This is like, in the case of Plotinus' axe, the axe gets damaged beyond repair but an axe is still desired, and so a smith melts down the iron and reforges the axe.) But if the soul slips from the body, by desiring incorporeal things, then it doesn't return. (This is like no longer needing an axe, and so the smith melts it down and makes a pot or whatever.)

I've seen it said that the mystic's path is "faster" or "more direct" than other paths to the divine. I don't know if that's so, but if it is, the above gives the reason why: the basis of mysticism is love, and having a desperate love for something unearthly is perhaps the obvious form of the soul orbiting something else. (But I think that this is really just showing that mysticism is an effect, rather than a cause. It's not "faster," it's just that more of the way was hidden from view.)

This is one of the meanings of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Orpheus looked back as he ascended from the underworld and was thereby denied bliss.

This is why Dorothy could always return to Kansas whenever she wanted: her desire was only for home. Even with all the other things she accomplished, it was all in the service of that one goal.

Many religions teach that desire is evil and one must purge themselves of it. But this isn't quite right: it's that earthly desire binds one to the earth, but heavenly desire binds one to heaven. (I guess it's right if you assume that earth if evil, but I think that's kinda silly.)

If you hate life, great! That's as good a starting point as any.

I guess none of this is new or surprising, but it's on my mind. Maybe writing it out will help me get back to sleep.

I suppose it is no surprise that vegetative is the lowest form of aitherial existence, since lovely Luna—who governs growth and reproduction—resides in the lowest sphere of the æther and is the special shepherd of vegetative life.

On the other end of the scale, should it be any surprise that the spiritual life is one of loneliness, melancholy, and pain? After all, the spiritual life brushes the upper edge of the aitherial, and the ruler of the highest sphere is inexorable Saturn, the great Teacher of this world.

I was reading Jowett's translation of the Symposium today, and noticed something curious in the section on the nature of daimons.

Previously, when I had cited it, I used Harold Fowler's translation: "[The spiritual possesses the power of] interpreting and transporting human things to the gods and divine things to men; entreaties and sacrifices from below, and ordinances and requitals from above: being midway between, it makes each to supplement the other, so that the whole is combined in one. Through it are conveyed all divination and priestcraft concerning sacrifice and ritual and incantations, and all soothsaying and sorcery. God with man does not mingle: but the spiritual is the means of all society and converse of men with gods and of gods with men, whether waking or asleep. Whosoever has skill in these affairs is a spiritual man to have it in other matters, as in common arts and crafts, is for the mechanical. Many and multifarious are these spirits, and one of them is Love."

But Jowett translates this section as follows: "[Love] interprets between gods and men, conveying and taking across to the gods the prayers and sacrifices of men, and to men the commands and replies of the gods; he is the mediator who spans the chasm which divides them, and therefore in him all is bound together, and through him the arts of the prophet and the priest, their sacrifices and mysteries and charms, and all prophecy and incantation, find their way. For God mingles not with man; but through Love all the intercourse and converse of God with man, whether awake or asleep, is carried on. The wisdom which understands this is spiritual; all other wisdom, such as that of arts and handicrafts, is mean and vulgar. Now these spirits or intermediate powers are many and diverse, and one of them is Love."

To highlight the difference: Fowler makes Diotima to say that daimons generally are responsible for all interaction between the divine and mortal worlds, while Jowett mades Diotima to say that the daimon of Love specifically is responsible for the same. This is a tremendous difference, theologically speaking, and not being a Greek scholar I couldn't say which is more accurate to the original. What's fascinating, though, is that, speaking as a mystic, both are accurate to my experience and I struggle to say which is a better description.

Thomas Taylor, for whatever it's worth, translates this section as follows: "[The dæmon-kind possesses the power and virtue] to transmit and to interpret to the Gods, what comes from men; and to men, in like manner, what comes from the Gods; from men their petitions and their sacrifices; from the Gods, in return, the revelation of their will. Thus these beings, standing in the middle rank between divine and human, fill up the vacant space, and link together all intelligent nature. Through their intervention proceeds every kind of divination, and the priestly art relating to sacrifices, and the mysteries and incantations, with the whole of divination and magic. For divinity is not mingled with man; but by means of that middle nature is carried on all converse and communication between the Gods and mortals, whether in sleep or waking. Whoever has wisdom and skill in things of this kind is a dæmoniacal man: the knowing and skillful in any other thing, whether in the arts, or certain manual operations, are illiberal and sordid. These dæmons are many and various. One of them is Love."

I trust Taylor more than the others here, and anyway assigning these powers to daimons generally matches the rest of the Neoplatonists. The reason I tend to equate these powers with Love specifically, of course, is that my daimon is under the rulership of Venus, which has a tendency to conflate and confuse and mingle such things!

My brain has been much too shot to dig very far into Plotinus lately, so I've been reading some lighter material. Yesterday, I finished P. M. H. Atwater's Beyond the Light: The Mysteries and Revelations of Near-Death Experiences. I'm never sure how seriously to take this stuff, as it's so heavily colored by Evangelical Christianity and New Ageism (neither of which I have much respect for, I'm afraid), but one thing stuck out to me of unusual interest.

Atwater's thesis is that near-death experiences are simply one of many kinds of spiritual awakening, just like more "standard" mystical experiences or those brought on by rigorous training or austerities, and that they exhibit the same range of symbolic communication. And as an example of a symbol, she offers the color yellow:

For those near-death survivors who could recall, the first color encountered during their experience was usually either yellow or yellow-gold. Some described it as just plain gold. Others saw it as more of a yellow-white, gold-white, or radiant white. Invariably, survivors commented on how different that color or light seemed; bright, and yet somehow easy on the eyes and not at all like the yellow-gold tones of the earth. [...]

People who are learning how to have an out-of-body-experience go through basically the same range of color hues in the initial manner as do near-death experiencers. Their first awareness of sight is usually as if through a yellow screen or filter. Yellowish colorations often continue until full separation between consciousness and body connections are made, then colored vision is restored. The more advanced the individual, the less yellow tinge to what they see. (For ten years I taught people how to "astral travel." The yellow filtering occurred so often, that I came to depend on it as a signal that some type of genuine separation was taking place.) [...]

In the language of symbology, yellow is considered a cross-over color—the harbinger of change. Tradition has it, for instance, that the sudden preference for yellow signifies that a person's life is about to change, that new, exciting times are ahead, with increased energy, enthusiasm, and upliftment. Yellow has always been thought of as a revitalizing tonic, a sign of spring, vigor, cheerfulness, new birth.

The reason this is interesting to me is that both of the two "transcendental" experiences I've had came with the sense of seeing the world through a gold-colored filter. In fact, the second of these is memorialized very simply in my diary:

29 Sep 2011

everything is glowing gold

The memory of that experience is very, very dim these days, but if I remember aright, I was going through a period of unbearable stress and was walking to work across town on a damp, overcast morning. While walking, I was watching one of those little streams that form after a rainstorm on the sides of roads, running down the street and pooling here and there in little, foamy ponds. I was watching one of these when, suddenly, a "switch" flipped in me and everything—the puddle, the clouds, the trees, people, buildings, everything—seemed to glow from within with golden light. I had the sense of joy and peace and of simply knowing that all these glowing things were connected, beautiful, and perfect and right just the way they were. (In fact, this was a source of some hilarity to me: I lived and worked in the rust belt, and the town was a literally crumbling old industrial city, as ugly as can be—and yet here it was, ugly and indescribably beautiful at the same time!) The color and glow and sense continued for about thirty-six hours as I went through my normal workaday routine, slowly fading over that time.

Strangely, after the experience faded, nothing seemed changed; and while I kept on meditating and studying, other than an odd experience or two, everything stayed the same as ever until 2019, when I took up divination during another period of unbearable stress, which opened the door to a proper spiritual life.

Porphyry wrote in his Life of Plotinus (§10):

Amelius was scrupulous in observing the day of the New Moon and other holy days, and once asked Plotinus to join in some such celebration. Plotinus refused: "It is for those Beings to come to me, not for me to go to them."

What was in his mind in so lofty an utterance we could not explain to ourselves and we dared not ask him.

I can't be sure what was in Plotinus' mind, and I am not yet halfway through his work, but I have a theory.

Plotinus rarely speaks of the cosmic gods. I think he's discussed Zeus and Aphrodite Pandemos once each (in the same place, no less), but of the other Olympians he has said nothing at all. Similarly, he's discussed the planets collectively a couple times, but only in the context of larger topics (like Fate and Providence). No, he spends all his time talking and thinking of the hypercosmic Gods: the Good (e.g. Ouranos), the Nous (e.g. Kronos), and Soul (e.g. Aphrodite Ourania) are referenced dozens of times in each and every chapter, and his whole philosophy is based on understanding the interaction of these Three and how it explains the properties of lower things (which are presumed to act in mimicry of Them).

It is as if this world is too small for Plotinus, the questions it presents too simple to hold interest for him, its gods—while worthy of respect—are merely the regents of a backwater. He seeks a larger world, he seeks more intricate puzzles, he seeks greater Gods.

Every visionary describes their spiritual visions from the vantage point of their culture and religion and closely-held beliefs. For example, most visionaries say all is One, but Zoroaster has his Ahriman and Christian mystics their Satan. For another, visionaries variously describe the Ultimate as pure light, pure love, or pure knowledge. For another, visionaries describe those who guide them in their visions as a dead friend, or a dead relative, or Virgil, or their guardian angel, or some arbitrary angel, or Jesus Christ Himself, or...

Is that not strange? Why should that be? Is not the spiritual experience universal?

I'm not sure it is. It seems to me that there's three points at which the perspective of a visionary might diverge:

We have no guarantee that different human souls, even those from the same part of this material world, go to the same segment of the spiritual world (which is much bigger than the material world).

Most mystical visions state that souls enter the world in order to grow. Different visionaries may therefore be at different "stages" of growth, and so have a different perspective on what they see during a vision, or even may be directed by their guides towards different experiences appropriate to their "stage" of growth.

All visionary experiences we have access to must be once again brought back down into the material world. This means that even a "pure" visionary experience must be remembered and described through the lens of the human vehicle, and thus may be colored by that vehicle.

Add it all up, and I might recommend one to either read widely about visionary experiences from different cultures and religious viewpoints so one can compare and contrast them, or else avoid them entirely and focus on one's own experiences exclusively.

I've lamented before how very long life seems to be. I was contemplating this again in light of Plotinus' assessment of time.

Einstein, it is said, explained relativity by saying, "When you sit with a nice girl for two hours you think it's only a minute, but when you sit on a hot stove for a minute you think it's two hours." In the same way, it seems to me that Time has a dual nature: it is short to the degree one is satisfied and long to the degree one is dissatisfied.

Plotinus said that Soul's motion is the cause of Universal Time and that each individual soul's motion is the cause of one's personal experience of time. But one's soul can very easily be torn in two directions: its lower part inclined towards the material and its upper part inclined towards the immaterial simultaneously. I think this wishing for both where one is and where one is not is the cause of those who report time feeling both fast and slow at once.

If anyone is interested in an account of what one's relationship with their daimon looks like, I found Ælius Aristides' Sacred Tales fascinating and worthy of study. It's very clear that Aristides' daimon is a Solar one, and I found it helpful to compare and contrast the directions he was led with the directions my own Venereal tutelary leads me.

I read Behr's translation; a copy can be found on the Internet Archive.

I think I am on safe ground (for example, Porphyry's Sentences XXXII, On the Gods and the World VIII (with Murray's note), etc.) to venture that there are simply four realms of being for the Neoplatonists: the One, Mind, Soul, and Bodies (plural). (If I were to put on my Empedocles hat, these are simply fire, air, water, and earth, transposed an octave higher.)

So perhaps our cosmos can be analogized something like this:

| Realm | Root | Size | Virtue | Computational Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| material | bodies | finite (bounded) | civic | finite state machine |

| aitherial | spirits | finite (unbounded) | purificatory | Turing machine |

| empyrean | Soul | infinite | contemplative | oracle machine |

| intelligible | Mind | trans-infinite | archetypal | [all of them] |

| unitary | the One | [transcendant] | [transcendant] | [transcendant] |

(It is perhaps folly to distinguish the material from the aitherial, as they are inextricably bound together and anyway of a similar nature. Still, perhaps it is useful to distinguish them in the same sense that the first step upon a journey, while still within one's own home, is nonetheless somehow distinct.)

I think this is a line of argument in favor of the Church-Turing Thesis: if you want to go beyond a Turing machine, you're gonna have to leave this world behind.

This comes from Porphyry's On Abstinence From Killing Animals II.36–43, speaking about the nature of spirit-beings and the sacrifice of animals:

(Gillian Clark's translation, very hastily transcribed, so I apologize for any errors.)The Pythagoreans, who are committed students of numbers and lines, made their main offering to the gods from these. They call one number Athena, another Artemis, and likewise another Apollo; and again they call one justice and another temperance, and similarly for geometrical figures. And they so pleased the gods with such offerings that they obtained their help when invoking each one with their dedications, and often used them for divination and for anything they needed in investigation. But for the gods within the heaven, the wandering and the fixed (the sun should be taken as leader of them all and the moon second) we should kindle fire which is already kin to them, and we shall do what the theologian says. He says that not a single animate creature should be sacrificed, but offerings should not go beyond barley-grains and honey and the fruits of the earth, including flowers. "Let not the fire burn on a bloodstained altar," and the rest of what he says, for what need is there to copy out the words? Someone concerned for piety knows that no animate creature is sacrificed to the gods, but to other daimones, either good or bad, and knows whose practice it is to sacrifice to them and to what extent these people need to do so. For the rest, "let it remain unsaid" by me; but it is not blameworthy to set before those of good understanding, to illuminate the discussion, thoughts which some Platonists have made public. This is what they say.

The first god, being incorporeal, unmoved and indivisible, neither contained in anything nor bound by himself, needs nothing external, as has been said. Nor does the soul of the world, which by nature has three-dimensionality and self-movement; its nature is to choose beautiful and well-ordered movement, and to move the body of the world in accordance with the best principles. It has received the body into itself and envelops it, and yet is incorporeal and has no share in any passion. To the other gods, the world and the fixed and wandering stars—visible gods composed of soul and body—we should return thanks as has been described, by sacrifices of inanimate things. So there remains the multitude of invisible gods, whom Plato called daimones without distinction. People have given some of them names, and they receive from everyone honours equal to the gods and other forms of worship. Others have no name at all in most places, but acquire a name and cult inconspicuously from a few people in villages or in some cities. The remaining multitude is given the general name of daimones, and there is a conviction about all of them that they can do harm if they are angered by being neglected and not receiving the accustomed worship, and on the other hand that they can do good to those who make them well-disposed by prayer and supplication and sacrifices and all that goes with them.

But the concept of daimones is confused and leads to serious misrepresentation, so it is necessary to give a rational analysis of their nature; for perhaps (they say) it is necessary to show why people have gone astray about them. So the following distinction should be made. All the souls which, having issued from the universal soul, administer large parts of the regions below the moon, resting on their pneuma but controlling it by reason, should be regarded as good daimones who do everything for the benefit of those they rule, whether they are in charge of certain animals, or of crops which have been assigned to them, or of what happens for the sake of these—showers of rain, moderate winds, fine weather, and the other things which work with them, and the balance of seasons within the year; or again, for our sake, they are in charge of skills, or of all kinds of education in the liberal arts, or of medicine and physical training and other such things. It is impossible for these daimones both to provide benefits and also to cause harm to the same beings. Among them must be numbered the "transmitters," as Plato calls them, who report "what comes from people to the gods and what comes from the gods to people," carrying up our prayers to the gods as if to judges, and carrying back to us their advice and warnings through oracles. But the souls which do not control the pneuma adjacent to them, but are mostly controlled by it, are for that very reason too much carried away, when the angers and appetites of the pneuma lead to impulse. These souls are also daimones, but may reasonably be called maleficent.

All these, and those that have the opposite power, are unseen and absolutely imperceptible to human senses. For they are not clad in a solid body, nor do they all have one shape, but they take many forms, the shapes which imprint and are stamped upon their pneuma are sometimes manifest and sometimes invisible, and the worse ones sometimes change their shape. The pneuma, insofar as it is corporeal, is passible and corruptible. Though it is so bound by the souls that the form endures for a long time, it is not eternal; for it is reasonable to suppose that something continuously flows from them and that they are fed. In the good daimones this is in balance, as in the bodies of those that are visible, but in the maleficent it is out of balance; they allot more to their passible element, and there is no evil that they do not attempt to do to the regions around the earth. Their character is wholly violent and deceptive and lacking the supervision of the greater divine power, so they usually make sudden intense onslaughts, like ambushes, sometimes trying to remain hidden and sometimes using force. So passions which come from them are acute. But healing and setting to rights, which are from the better daimones, seem slower, for every good thing is gentle and consistent, progressing in good order and not going beyond what is right. If you think like this, it will never be possible for you to fall into the worst of absurdities: that is, supposing that there is bad in the good ones and good in the bad ones. This is not the only way in which the argument is absurd, but most people have acquired the most contemptible ideas even about the gods, and pass them on to others.

One thing especially should be counted among the greatest harm done by the maleficent daimones: they are themselves responsible for the sufferings that occur around the earth (plagues, crop failures, earthquakes, droughts, and the like), but convince us that the responsibility lies with those who are responsible for just the opposite. They evade blame themselves: their primary concern is to do wrong without being detected. Then they prompt us to supplications and sacrifices, as if the beneficent gods were angry. They do such things because they want to dislodge us from a correct concept of the gods and convert us to themselves. They themselves rejoice in everything that is likewise inconsistent and incompatible; slipping on (as it were) the masks of the other gods, they profit from our lack of sense, winning over the masses because they inflame people's appetites with lust and longing for wealth and power and pleasure, and also with empty ambition from which arises civil conflicts and wars and kindred events. Most terrible of all, they move on from there to persuade people that the same applies even to the greatest gods, to the extent that even the best god is made liable to these accusations, for they say it is by him that everything has been thrown topsy-turvy into confusion. It is not only lay people who are victims of this, but even some of those who study philosophy; and each is responsible for the other, for among the students of philosophy those who do not stand clear of the general opinion come to agree with the masses, whereas the masses, hearing from those with a reputation for wisdom opinions which agree with their own, are confirmed in holding even more strongly such beliefs about the gods.

Literature, too, has further inflamed people's convictions, by using discourse designed to astound and enchant, able to cast spells and to create belief in the most impossible things. But one must be firmly convinced that the good never harms and the bad never benefits. As Plato says, "cooling is not done by heat but by its opposite," and similarly "harm is not done by the just man." Now the divine power must by nature be most just of all, or it would not be divine. So this [harmful] power, and this role, must be separated from the beneficent daimones for the power which is naturally and deliberately harmful is the opposite of the beneficent, and opposites can never occur in the same. The maleficent daimones harass mortals in many respects, some of them important, but in every respect there is no way that the good daimones will neglect their own concerns: they forewarn, so far as they are able, of the dangers impending from the maleficent daimones, by revelations in dreams, or through an inspired soul, or in many other ways. And everyone would know and take precautions, if he could distinguish the signs they send; for they send signs to everyone, but not everyone understands what the signs mean, just as not everyone can read what is written, but only the person who has learned letters. But it is through the opposite kind of daimones that all sorcery is accomplished, for those who try to achieve bad things through sorcery honour especially these daimones and in particular their chief.

These daimones abound in impressions of all kinds, and can deceive by wonder-working. Unfortunate people, with their help, prepare philtres and love-charms. For all self-indulgence and hold of riches and fame comes from them, and especially deceit, for lies are appropriate to them. They want to be gods, and the power that rules them wants to be thought the greatest god. It is they who rejoice in the "drink-offerings and smoking meat" on which their pneumatic part grows fat, for it lives on vapours and exhalations, in a complex fashion and from complex sources, and it draws power from the smote that rises from blood and flesh.

So an intelligent, temperate man will be wary of making sacrifices through which he will draw such beings to himself. He will work to purify his soul in every way, for they do not attack a pure soul, because it is unlike them. If it is necessary for cities to appease even these beings, that is nothing to do with us. In cities, riches and external and corporeal things are thought to be good and their opposites bad, and the soul is the least of their concerns. But we, as far as possible, shall not need what those beings provide, but we make every effort, drawing on the soul and on external things, to become like God and those who accompany him—and this happens through dispassion, through carefully articulated concepts about what really is, and through a life which is directed to those realities—and to become unlike wicked people and daimones and anything else that delights in things mortal and material. So we too shall sacrifice, in accordance with what Theophrastus said. The theologians agreed with this, knowing that the more we neglect the removal of passions from the soul, the more we are linked to the evil power, and it will be necessary to appease that too. For as the theologians say, those who are bound by external things and are not yet in control of passions must avert that power too, for if they do not, their troubles will not cease.

If there is a short story more fine-tuned to my disposition than Lafcadio Hearn's Kimiko, I have not come across it. At once joyful and sad, I highly recommend it.

It can be found on Project Gutenberg: the first story in this collection or the last story in this one.

Who indeed, I suppose, could give greater voice to the changing of the guard (e.g. the move from the Age of Aries to the Age of Pisces, cf. Five Stages of Greek Religion V) than the Lyrist Himself?

Aye, if ye bear it, if ye endure to know

That Delphi's self with all things gone must go,

Hear with strong heart the unfaltering song divine

Peal from the laurelled porch and shadowy shrine.

High in Jove's home the battling winds are torn,

From battling winds the bolts of Jove are born;

These as he will on trees and towers he flings,

And quells the heart of lions or of kings;

A thousand crags those flying flames confound,

A thousand navies in the deep are drowned,

And ocean's roaring billows, cloven apart,

Bear the bright death to Amphitrite's heart.

And thus, even thus, on some long-destined day,

Shall Delphi's beauty shrivel and burn away,—

Shall Delphi's fame and fane from earth expire

At that bright bidding of celestial fire.

(Apollo, as quoted by Porphyry, as quoted by Eusebius, and as translated Frederic William Henry Myers.)

[The descent of the souls of men] is deepened since [their spirit] is compelled to labour in care of the [needy body] into which they have entered. But Zeus, the father, takes pity on their toils and makes the bonds in which they labour soluble by death and gives respite in due time, freeing them from the body, that they too may come to dwell there where the Universal Soul, unconcerned with earthly needs, has ever dwelt.

(Plotinus, Enneads IV iii §12.)

It may seem strange, from our perspective on the earth, to think of death as the gift the Gods give to us in pity, but I have another example like it.

I have very severe allergies to many things, and one of the worst of these is hay fever season. It is not merely itchy eyes or a runny nose for me, though; my lungs and skin catch fire, my throat and eyes swell shut, and I become unable to breathe, eat, sleep, or generally function at all. In time, my wife and I have learned to manage this very carefully through a quarantine protocol, and while I'm more-or-less confined to part of the house, at least I can live normally otherwise.

Back in New York, hay fever season lasted late July through late August—that is, when the Sun is in Leo. (I have long wondered about this—guess which planet rules my sixth house?) This was also when the sunflowers were in bloom, and while I really like sunflowers, I've always had to enjoy them from a distance.

Here in Oklahoma, hay fever season began in June and is still ongoing—I expect it to continue for the rest of the month or so. One might lament a three-month house arrest, but the gods are merciful and given me, too, a gift of their strange sort of pity: a volunteer sunflower sprang up right behind the house, in easy view from the window, for me to enjoy up close. But not only this, but it seems to act as a clock for the allergies: it began to blossom in June, right as I could no longer go out, and has been in continuous bloom since then but for a single week—and it happened to be a single week where the drought had been severe enough to reduce the pollen, letting me go out for a few days. (Conveniently, this coincided with an appointment that I needed to keep.) So this sunflower is the gods' good messenger to me, warning me of danger and safety—and I imagine the last of its flowers will wilt when it is safe for me to again leave the house for the autumn.

So rather than complain about what kind of divinity should cause me to be locked up for a substantial fraction of the year, it is better to realize that it was men who poisoned the plants with their chemicals and sickened my body with autoimmune disease, but it is the providence of the gods that help me to bear it.

After reading a few accounts of people's mystical experiences, I wonder if the nature of one's mystical experiences are determined by one's guardian angel. For example, a mystic with a Mercurial guardian angel might experience a dissolving of boundaries—becoming one with this or that thing—while one with a Venereal guardian angel might experience an overwhelming sensation of love and beauty.

O God ineffable, eternal Sire,

Throned on the whirling spheres, the astral fire,

Hid in whose heart thy whole creation lies,—

The whole world's wonder mirrored in thine eyes,—

List thou thy children's voice, who draw anear,

Thou hast begotten us, thou too must hear!

Each life thy life her Fount, her Ocean knows,

Fed while it fosters, filling as it flows;

Wrapt in thy light the star-set cycles roll,

And worlds within thee stir into a soul;

But stars and souls shall keep their watch and way,

Nor change the going of thy lonely day.Some sons of thine, our Father, King of kings,

Rest in the sheen and shelter of thy wings,—

Some to strange hearts the unspoken message bear,

Sped on thy strength through the haunts and homes of air,—

Some where thine honour dwelleth hope and wait,

Sigh for thy courts and gather at thy gate;

These from afar to thee their praises bring,

Of thee, albeit they have not seen thee, sing;

Of thee the Father wise, the Mother mild,

Thee in all children the eternal Child,

Thee the first Number and harmonious Whole,

Form in all forms, and of all souls the Soul.

(An anonymous hymn, simply titled "an oracle concerning the Eternal God" and suggestively quoted in the same manuscript as Porphyry to Marcella, translated by Frederic William Henry Myers.)

Was curious, so I went looking. Search engines memory-hole the Internet pretty quickly these days, so it was difficult to dig up much, but I figure it's around 5/7 of the population and that it's been pretty consistent for the last few decades.

| Year | Poll | Pollster |

|---|---|---|

| 1978 | 54% | Gallup |

| 1994 | 72% | Gallup |

| 1996 | 72% | Gallup |

| 2001 | 79% | Gallup |

| 2001 | 77% | Scripps |

| 2004 | 78% | Gallup |

| 2006 | 81% | AP-AOL |

| 2007 | 75% | Gallup |

| 2007 | 68% | Pew |

| 2005–7 | 61% | Baylor |

| 2011 | 77% | AP-GfK |

| 2014 | 77% | AP-GfK |

| 2016 | 72% | Gallup |

| 2023 | 69% | AP-NORC |

According to my diary, about a decade ago, I was sitting in a cafe and overheard an elderly man ranting to his wife, "Kids these days don't appreciate books!" He said this even as I and many other young people were sitting around him, reading.

I was reminded of this today. I was in the library when I heard two teenagers come upstairs wondering to themselves where to find the Divine Comedy. I happened to know where it was—right next to Plotinus!—so I went a few aisles over, pulled it out, came back, and handed it to them. They lit up.

I've been having quite a lot of fun playing with geometric constructions lately, and I have another one for you all today: a solution to Napoleon's Problem (that is, inscribing a square in a given circle using only a pair of compasses).

It's a famously tricky problem, and to be honest, I came up with this solution by accident while exploring something else. Nonetheless, I suspect this solution—involving six circles—is the simplest one possible, but I haven't managed to prove it yet.

I'm not sure if I've got this right, but I was thinking...

The Mind is motionless, and its Act is simply to Be. So it Knows everything there is to Know simply be virtue of Existing.

But the Soul is mobile, and its Act is to Do. So while from the perspective of the Mind, the Soul Knows everything there is to Know, from the Soul's perspective, It only Knows it by Doing it.

And this is why we exist here in the world. If something here in the material is discovered for the first time (from the perspective of time, of course), then it finally becomes Known to the Soul and is immediately accessible thereafter to all souls. (At least those who are focused "upwards" rather than "downwards.")

That is, the things we do here is the Soul coming to Know Itself, in imitation of the Mind.

The 3-4-5 triangle is my desert-island geometric fact: if you have a triangle with a sides of length 3, 4, and 5, it's a right triangle. This is great because it's super easy to mark a rope into 3+4+5=12 equal lengths, and this means it's super easy to make yourself a right triangle. I've used this before to lay out an orchard, making sure all the rows were nice and parallel, and it worked beautifully.

Because it's so easy to make a 3-4-5 triangle directly, it seems pretty silly to go to much greater lengths to make one using a pair of compasses, but let's not let mere uselessness stop us! After all, there's the Taoist saying: "When purpose has been used to achieve purposelessness, the thing has been grasped." ;)

I'm feeling playful, so in honor of the sovereign Sun whose day it is, and his dutiful son Pythagoras, let's pick up our compasses and hop to it:

Given points A and B, draw

then triangle HIE is a 3-4-5 triangle. I'm not going to write up a full proof right now, but a quick sketch runs like this: let's define AB=2. It can be shown that EAB is collinear, therefore EB=EI=EA+AB=2×AB=4. Suppose line FG intersects line AB at X: it can be shown that AX=3/2. H is the reflection of A about line FG and FG is perpendicular to AB, therefore EABH is collinear and AH=HI=AX+XH=2×AX=3. Finally, EH=EA+AH=AB+AH=5.

I believe this to be the simplest possible construction (that is, using the fewest circles) of such a triangle using only compasses. (There are much easier ways to draw a right angle, though!)

It always seemed odd to me that one can trisect a line but not an angle. It's one of those things that makes sense arithmetically—trisecting an angle requires a cubic equation, and circles are only quadratic—but I don't have a good visual intuition for why that's so.

I set out to play around with trisecting a line in an attempt to get a better feel for the problem, but it didn't help: the numbers fell out very easily and I feel like I have no better an understanding than when I started. Oh well.

Given points A and B, draw

then I trisects AB. This one's straightforward to analyze using trigonometry. Let's first observe that EABF are all collinear, so we'll just worry about distances along the line EF. If we define AB=1, then EA=BF=1 as well, making EF=EA+AB+BF=3. FC=CD=√3. Suppose GH intersects EF at X: using the formula for the intersection of two circles, EX=(3²-√3²+2²)/(2·3)=5/3, therefore AX=EX-EA=2/3 and XB=AB-AX=1/3. I is the reflection of B about GH, therefore IX=XB=1/3 and AI=AX-IX=1/3.

Here is another construction for you all. (It must seem like I must do nothing but these, but in my defense, I've been sick as a dog for a long time and I seem to be fit for nothing but mathematics when I'm sick.)

Given points A and B, draw

then triangle CDI is Kepler's triangle. (Yes, that Kepler, the pre-eminent astronomer.) This triangle is the unique right triangle with edges forming a geometric progression: 1:x:x². (Curiously, the Great Pyramid of Giza when it was built—it has now weathered considerably—had proportions matching Kepler's triangle to three decimals.)

I found this by doodling around and ending up with this bizarre construction:

Lines EABF and IDJ sure look parallel, don't they? But that's weird, I was just doodling randomly and these circles have pretty arbitrary radii, so it wouldn't make sense for the intersection points to line up so nicely. So I just had to prove to myself that they were, in fact, parallel. I'll spare you my original trigonometric proof, which involved walking through five triangles using the law of cosines,* and give you a much simpler sketch using our circle-circle intersection formula. Due to Kurt Hofstetter, CH has a radius of √3ϕ. One can use the Pythagorean theorem to derive that circle HE has a radius of √6. The intersection points of circles CH and HE are therefore located at distance ((√3ϕ)²-(√6)²+(√3ϕ)²)/(2√3ϕ)=√3 from C to H. But CD=√3. Therefore CDI is a right angle, and lines AB and ID are, indeed, parallel. But the magic trick is in applying the Pythagorean theorem to triangle CDI to find DI=√3√ϕ—but √ϕ is a pretty funny number, isn't it? It means that CD:DI:CI=1:√ϕ:ϕ—which is indeed 1:x:x²—and therefore triangle CDI is Kepler's triangle. Crazy!

* Fun fact: back in high school, I ignored all the various theorems that my geometry teacher wanted me to use and instead drew tons and tons of triangles, proving whatever construction was requested using trigonometry. This was nice and easy to do—no thinking required—but the proofs routinely ran to multiple pages. About halfway through the school year my teacher stopped bothering to check my proofs. I know this since I started giving her faulty proofs in order to test her. ;)

The highlighted curve is called Moss's Egg. I was surprised to find a way to construct it using only 8 circles! This is because circles naturally want to generate √3's, so usually it'd take extra effort to generate the √2 proportions the egg demands, but it turned out to only require going a single circle out of my way.

I managed to prove using exhaustive computer search that this is the only way (but for symmetries, rotations, etc.) to construct Moss's Egg with eight or fewer circles.

(But who is Moss? The link cites Dixon's Mathographics, but I have a copy and Dixon doesn't say!)

A very common traditional construction was, given a circle and a point on it, inscribe a regular polygon within it with a vertex at that point. I've completed my collection of non-exotic inscribed polygons using (I believe) as few circles as possible, and figured I'd share them in case anyone is interested.

(Regular decagons (10 sides) and pentadecagons (15 sides) are also commonly encountered, due to their appearance in Euclid, but I've omitted them for being of less interest with compass-only constructions.)

Triangle: Despite being so simple, the equilateral triangle is very wasteful, requiring four circles. (There are a number of ways to do it with four circles, though! This one happens to be identical to the hexagon's construction, below.)

Square: I've talked about Napoleon's Problem before, but here's a clean, easy-to-prove construction using six circles which I found while working on Moss's Egg.

Pentagon: Michel Bataille also gives a construction for this, but this one (using eight circles) is, I believe, the simplest possible. It is also very surprising! I've verified it using symbolic computation tools, but I haven't managed a geometric proof.

Hexagon: This construction is trivial: circles just love to form hexagons.

Octagon: This construction (using ten circles) isn't terribly elegant, but it has the merit of starting from the square construction, above, and being no worse than any other construction I've found.

Dodecagon: This construction (using nine circles) also starts from the square construction, above, and uses the fact that placing a circle at each of the square's corners forms a dodecagon. There's lots of other ways to make a dodecagon, but I don't believe any are simpler than this.

I found something neat! Let me share it with you.

Consider this lovely construction:

It's similar to the various solutions I've posted to Napoleon's problem—it's a square made out of six circles—but it's not quite the same since it's a circumscribed square rather than an inscribed square. I think it's beautiful because the construction exhibits so much symmetry.

(Did any of you ever play the game Riven way back when? If not, I recommend it—it's one of a very few I consider edifying—but in any case, this construction is terribly reminiscent of the art of that game.)

Anyway, if that were all, it'd be cute but not terribly exciting. But what's neat about it is that, by reflecting a few points around,...

...poof! you have a regular octagon! This construction takes only nine circles, compared to my previous best, which took ten. The trick, of course, is that I wasn't specifically trying to place this octagon anywhere in particular, and it happens to be more natural to construct √2 (as I did here) than it is to construct 1/√2 (as I did previously).

Still, those reflections aren't very efficient, and it feels like I ought to be able to construct a regular octagon using eight circles somehow...

You guys tired of geometry yet? No? Great! Neither am I! I found another neat thing I'd like to show you.

Back in 2002, Kurt Hofstetter showed how fundamental the golden ratio is by demonstrating a very simple construction using five circles:

I discovered today that he considerably undersells that construction. Not only does it contain the golden ratio, but it also contains the other two fundamental ratios of sacred geometry, √2 and √3. Consider this pentacle-like diagram:

In this diagram, notice the the dark circle in the bottom-center. If it has a radius of length 1, then the blue lines are of length √3, the green lines are of length √2, and the red line is of length ϕ. Thus it is almost trivial to construct any of the classical regular polygons—the triangle from √3, the square from √2, the pentagon from ϕ, or their multiples—within the dark circle. Indeed, the triangle is already present; the square and hexagon take a single additional circle each, while the pentagon requires two additional circles:

I haven't had much time today, but I'd like to explore this construction further...

A generation or two ago, the US Air Force conducted a study. It was trying to optimize the performance of it's fighter pilots by making them more comfortable in their aircraft, so they measured different parts of their pilots—torso length, upper leg length, lower leg length, head circumference, etc.—and in the end reduced their pilots to twenty or so numbers. They then designed their aircraft cockpits for the average of these numbers, so that everyone would be fairly close to them and more comfortable.

As it turned out, every single pilot hated the redesigned cockpits, and the reason is simple: the average pilot did not exist. While all the pilots were close to average on most metrics, there was always at least one—and usually more—where they differed significantly, and that metric was the cause of discomfort for that pilot.

The USAF was only considering physical measurements, but there is no reason to limit ourselves to those: we can just as easily consider measurements of opinions, or psychological characteristics, or whatever. So in the same way, we can say there's no such thing as an average person.

Let's look at this mathematically. Let's suppose the average distance between two people on any given metric is 1. We can use the Pythagorean theorem to find the average distance between them on any two given metrics, which is therefore √2, or around 1.4. This generalizes: if you consider any n metrics between two people, the average distance between them in this case would be √n—that is, the more metrics you consider, the more different two people are. The USAF looked at twenty metrics, so the average distance between two pilots was √20, or around 4.5× as different than they would have been on any one metric.

I think this idea of being "average" or "normal" is one of the most insidious memes of our time, since it's pushed on us for a particular and malicious reason.

If you look at the news, it's always "us" versus "them", "left" versus "right", "Republicans" versus "Democrats", etc. That is, the mass media attempts to frame discussion in terms of a single dimension. In light of the above, the reason for this is obvious: it's an attempt to group people together, so that one can divide and conquer them: when you only look at a single metric, any two people are pretty close together, so it's easy to stereotype them, label them, attack them; conversely, it's easy to get them to support you, since what's the alternative?

Perhaps, if you're lucky, you've been exposed to more nuanced political discussion, like the various "political compasses" that have floated around the Internet; but even these use only two or three metrics—and thus people are still able to be corralled into some small number of stereotypes—say, five or ten—which is still few enough that people can treat each other as abstractions rather than people.

(The mathematics of that is that the number of stereotypes needed for a given number of metrics is 2ⁿ: two for a single metric, four for two, eight for three, over a million for twenty, etc.)

But, of course, those stereotypes are averages, and there's no such thing as an average person. If we really wanted to accurately characterize a person's opinions, how many metrics would we need? I'm not sure, but it's definitely more than two or three, or even twenty. But if we're looking at even just twenty metrics, the number of stereotypes you'd need to keep in mind is too many for anyone to comprehend, and people are too different to easily corral.

The reality is, if you look at people as people, they're unique and beautiful and impossible to put in a box. Once you start measuring them, by one or two or twenty or any number of numbers, you've dehumanised them, abstracted them, turned them into a stereotype rather than an ensouled being containing a little fragment of Divinity.

The point of spirituality, of course, is to approach closer to the Divine. Seeing people as stereotypes distances you from the Divine. This is why so many spiritual traditions and teachers warn initiates away from politics: because politics and spirituality pull in different directions, are mutually exclusive.

I like how Porphyry put it in his Sentences: if one masters the civic virtues—which are political, as Plato described—they become a good neighbor. And that's good! But when one turns to spirituality, they've chosen to move past the civic virtues to the purifying virtues: they are no longer bound by the social or political arena, but a higher one; being a good neighbor is no longer good enough: one must strive to be a saint. When you turn to spirituality, you lose your born citizenship—a mere thing of the body—and apply for citizenship in the country of Love, where the Soul resides. And Soul is not disparate like bodies are: all life is one Life. It can be no longer possible to take sides or weigh policies, making politics impossible: all that is left is to transcend it.

Another way to put it, I think, is that social or political things are created by humans; in that sense, they're ontologically sub-human. Is not the point of spirituality to go above or beyond the merely human? So why focus downwards, rather than upwards?

Suppose you have a long rod, fixed at one end but freely swinging at the other. You wish to move the end of it some distance. If you grab the end and move it directly, you need to move your arm that distance to move the rod's end the same distance; but if you instead grab the rod in the middle, you only need to move your arm half as far to accomplish the same. This is because the rod, here, is acting as a lever; by grabbing it in the middle, you gain mechanical advantage, and can accomplish the same action with less effort.

Now, suppose you wish to make a change here in the material world, at the extremity of the cosmos. Is it better to make your efforts here, in the material? Or is it better to apply those same efforts partway "up" the cosmos in the world of spirit? ...

Spirituality is not and cannot be escapism, where one runs away from the world; rather, it is a means of embracing the world and attempting to engage with it more effectively. Heaven is not where you bliss out forever: it's where you see your hard work make more of a difference.

Are any of you familiar with the nursery rhyme, "Monday's Child?"

I hadn't heard it as a child, myself, but when I had children, I ran across it in quite a number of books on nursery rhymes. The version I'm familiar with runs as follows:

Monday's child is fair of face,

Tuesday's child is full of grace,

Wednesday's child is full of woe,

Thursday's child has far to go,

Friday's child is loving and giving,

Saturday's child works hard for a living,

And the child born on the Sabbath day

is bonny and blithe and good and gay.

Wikipedia has a decent page on it, indicating that some version of it was known in rural England as early as the 1500s, and recorded in print at least as early as the 1800s.

It is not hard to see this as a folk memory of the planetary days, to wit:

Sunday is the day of the Sun, associated with (among other things) an irrepressible nature;

Monday is the day of the Moon, associated with (among other things) a sensual nature;

Tuesday is the day of Mars, associated with (among other things) athleticism;

Wednesday is the day of Mercury, associated with (among other things) a mischievous nature;

Thursday is the day of Jupiter, associated with (among other things) an adventurous nature;

Friday is the day of Venus, associated with (among other things) love; and

Saturday is the day of Saturn, associated with (among other things) hard work.

The below biography of Porphyry is wrested, like the juice from an orange, from an essay on Greek Oracles by Frederic William Henry Myers. His object was to show how the history of Delphi parallels the history of Hellenic culture, but it is surprising that the end of each is punctuated by a single person, and so the biography of the nation includes the biography of the man.

I felt that it was worth transcribing and excerpting, not only for its literary merit but also for the sketch it draws of a fascinating person. It is, of course, impossible—given the gulf of years—to know whether such a sketch is in any way accurate, but the archetypal story it tells is one worth knowing, I think.

[...] It was destined that every seed which the great age of Greece had planted should germinate and grow; and a school was now to arise which should take hold, as it were, of the universe by a forgotten clew, and should give fuller meaning and wider acceptance to some of the most remarkable, though hitherto least noticed, utterances of earlier men. We must go back as far as Hesiod to understand the Neoplatonists.

For it is in Hesiod's celebrated story of the Ages of the World that we find the first Greek conception, obscure though its details seem—of a hierarchy of spiritual beings who fill the unseen world, and can discern and influence our own. The souls of heroes, he says, become happy spirits who dwell aloof from our sorrow; the souls of men of the golden age become good and guardian spirits, who flit over the earth and watch the just and unjust deeds of men; and the souls of men of the silver age become an inferior class of spirits, themselves mortal, yet deserving honour from mankind. The same strain of thought appears in Thales, who defines demons as spiritual existences, heroes, as the souls of men separated from the body. Pythagoras held much the same view, and, as we shall see below, believed that in a certain sense these spirits were occasionally to be seen or felt. Heraclitus held "that all things were full of souls and spirits," and Empedocles has described in lines of startling power the wanderings through the universe of a lost and homeless soul. Lastly, Plato, in the Epinomis brings these theories into direct connection with our subject [of Greek oracles] by asserting that some of these spirits can read the minds of living men, and are still liable to be grieved by our wrong-doing, while many of them appear to us in sleep by visions, and are made known by voices and oracles, in our health or sickness, and are about us at our dying hour. Some are even visible occasionally in waking reality, and then again disappear, and cause perplexity by their obscure self-manifestation.