All of the entries on this page are collected from my Dreamwidth blog.

Consider Adolf Hirémy-Hirschl’s painting Ahasuerus at the End of the World:

It depicts Ahasuerus, cursed to wander the world until Judgement Day, in the dark wastes at Time’s End. He is guided by the twin angels of Hope and Fear. Fallen Humanity lies at his feet, and ravens—harbingers of Death, of course, but also hard-won Wisdom—look on. Perhaps he has finally learned the lesson for which he was cursed.

Like all fine art, there is much to unpack in the painting, but the thing that caught me first is the figure of Humanity. She is depicted beautifully, despite being dead in a frozen world: she is neither frozen nor desiccated nor even pallid! So emphasizing the beauty of Humanity—while it lasted, anyway: beauty never lasts!—was a particular goal of the artist’s.

This is also true, I note, of the wise minds that composed geomancy. Puella, the figure of beauty, is also one of only two figures that generally depict a flesh-and-blood human being in a reading.

What a surprise this is to me! I have been taking it as an axiom that human beings are the very thing that snuff out the light of beauty from the world, rather than shine themselves. Clearly I got turned around, somewhere, and if I am to properly understand this material, it is worth unpacking where...

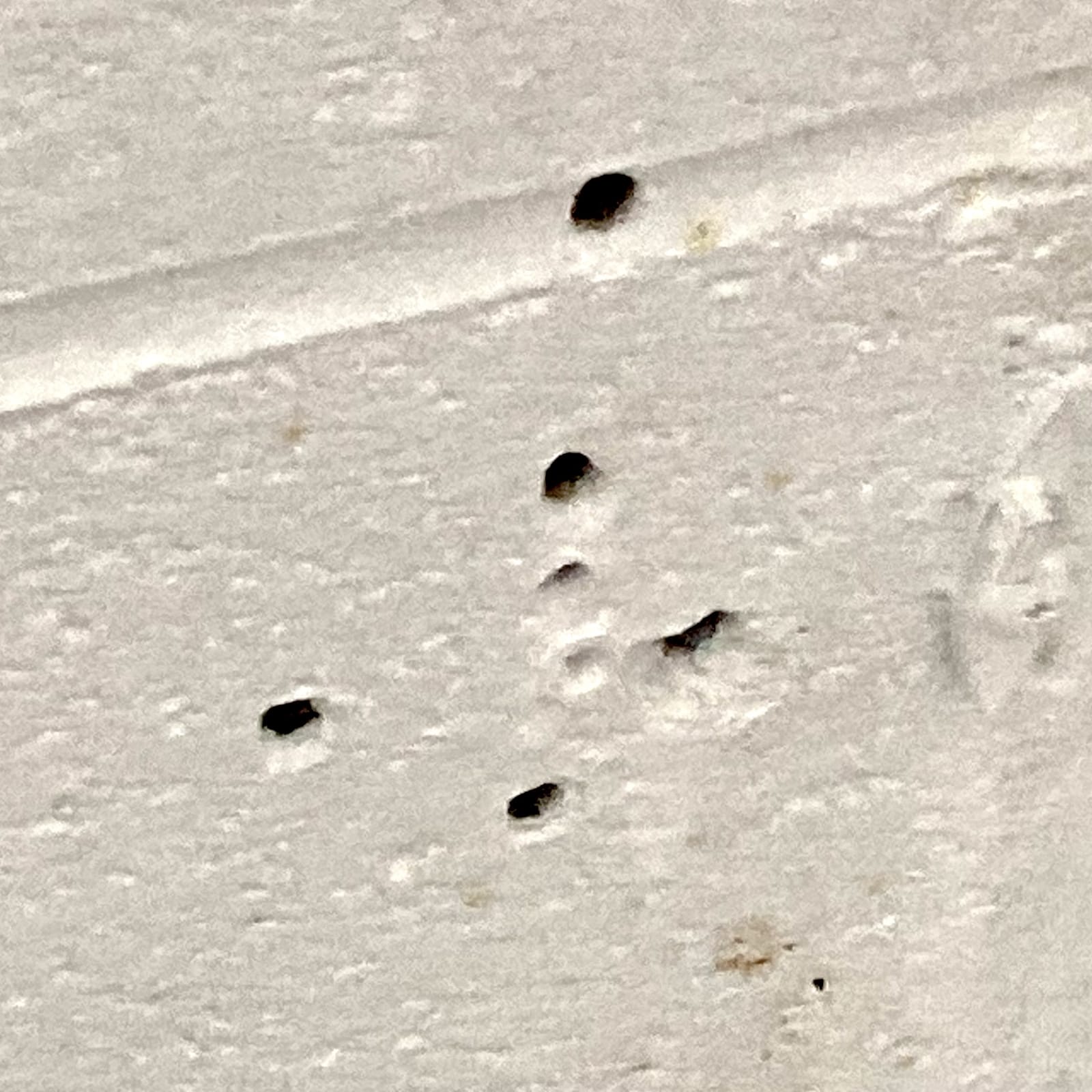

In a park in West Virginia, in the men’s restroom, there was a Puer drilled into the wall above the toilet. I know it’s just the former home of a wall-mounting bracket, but...

[I work in tech, which means all of my associates have been trained to only appreciate “scientific” thought and smugly dismiss “superstition.” Since I don’t fit that mold at all, and have a nasty habit of being unable to keep my big mouth shut, I’ve had to repeatedly articulate a defense of “mystical thinking.” Since I’ve said it so much, I figured I might as well write it down so I can refer back to it. I’ve placed it here in case it’s useful to anyone else.]

Are you familiar with Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem? Very briefly, it says that all systems of reasoning are either inconsistent or incomplete. Another way of characterizing this is that you can understand everything (but not for sure), or understand things for sure (but not everything), but—importantly—not both: it is impossible to understand everything for sure, even in theory. You can think of inconsistent thought as intuitive or mystical or “right brained,” and incomplete thought as analytical or scientific or “left brained.”

[I should note that this is an extremely hand-wavy explanation of the Theorem. Pedantic types will whine about how I’ve characterized it, but in my defense I have three justifications for doing so. First, fuck them. Second, it’s very difficult to explain something as complex and technical as the Theorem to a layman in a single paragraph. Third, since the human mind is capable of acting as a “formal system” (as defined by Gödel), it must be at least a “formal system” (at least in certain contexts), and therefore it must be subject to the same constraints as a “formal system” is (at least when used within those contexts).]

In the modern era, we have almost completely discarded intuitive thought in favor of analytical thought. This has bought us a lot of amazing things—refrigerators and computers and rocket ships and the Haber–Bosch process and so on—but at a steep cost: there are many things which we have simply lost the ability to think about at all, and I believe these blind spots to be a major cause of the dysfunction and alienation present in modern society.

Put another way, the scientific revolution has given us very sure footing in our thought, but has made us blind to what we don’t know. (And, anyway, nobody likes people who are too sure of themselves.)

On the other hand, there are many traditional systems of thought which, while not giving the same sure footing that analytical reasoning does, allow one to understand a much greater range of phenomena in ways that are practical to everyday living. And it is not as if one has to abandon scientific thought to use these: if one has many models, one is more likely to have a model appropriate for a given situation; the more maps one has, the better they can navigate. Even if you think, say, astrology has no scientific basis, there is nonetheless thousands of years of wisdom encoded in that system, and it is perhaps wasteful to “throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

Astrology isn’t the only example: mysticism and religion fall into this camp as well. These attempt to apprehend the whole range of human experience, and in my opinion do so... but the cost for this is that their models are paradoxical—no two religions describe the same phenomena in the same way, and in fact tend to describe them in mutually exclusive ways. So the tools have their limitations, but they still provide powerful ways of understanding life and human experience in ways that science is only beginning to approach, and then dimly.

Raymond Smullyan, the eminent logician, wrote that empiricism, positivism, and mysticism are not mutually exclusive, but mutually supportive: they can each understand phenomena that the others cannot. If we wish to understand life as best as we can, should we not use all the tools at our disposal?

A. We forget everything when we enter the world.

B. Why do we forget?

A. So we can remember what is important again.

B. Why do we remember?

A. It’s a purification process: in each pass, that which is not important is lost. The dross is left behind and only the fine remains. When one is fine enough...

There’s been a lot of discussion and debate about why astrology works (or why it can’t possibly work). Ever since western astrology was revived in the middle ages, the popular opinion has tended towards the scientific. Originally, this followed Ptolemy and Aristotle in ascribing the planets an elemental character; later, this followed Newton is ascribing the planets an invisible force akin to gravity; after Einstein theorized that gravity wasn’t a force after all, this ascribed the planets a wave theory akin to electromagnetism.

These are all well and good, but I’ve never found them convincing. But while reading Chris Brennan’s Hellenistic Astrology, I came across a theory that seems much more satisfactory. Evidently, the Mesopotamians didn’t believe the planets caused the effects we see here on earth any more than the arms of a clock cause it to be a particular time: rather, they’re simply a sign that provides information to those who know how to read it. Where did this sign come from? From Ea, god of water, wisdom, crafts, and mischief, who apparently made a colossal clock in the skies so that those who cared to study it—that is to say, the wise (his followers, naturally)—would always “know what time it is” and thereby possess an unfair advantage over those who did not.

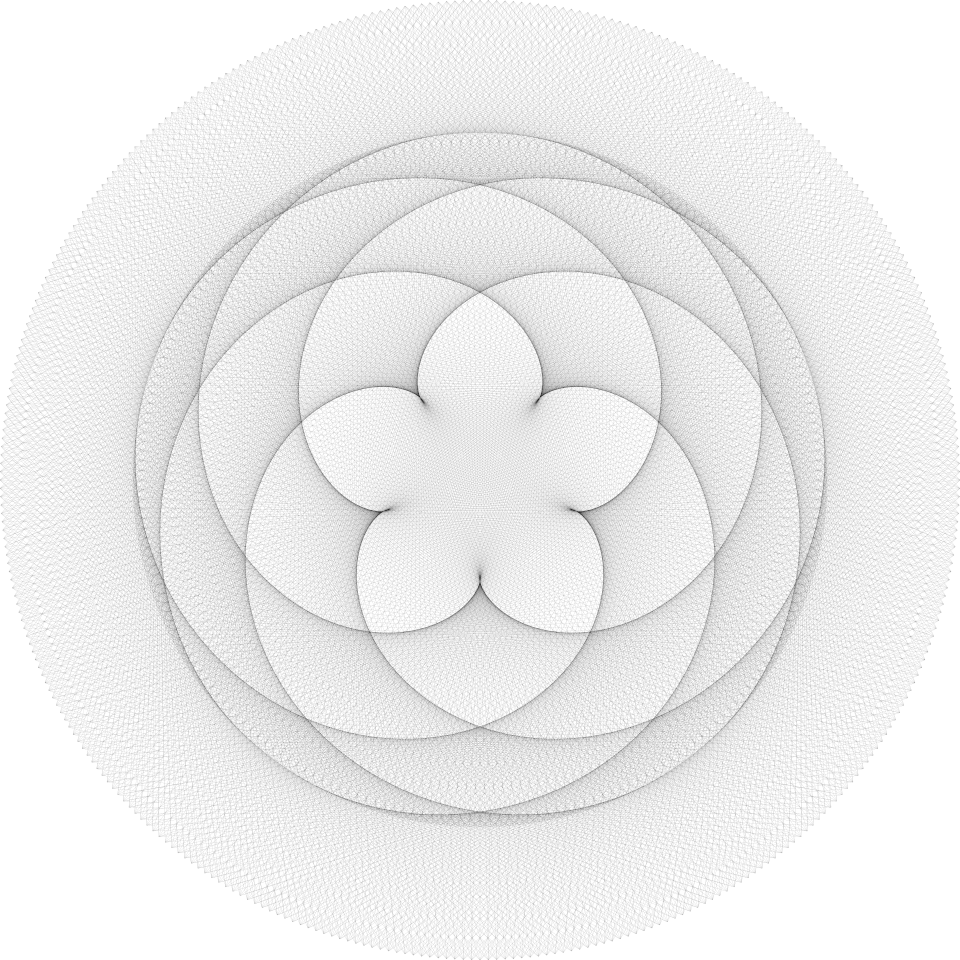

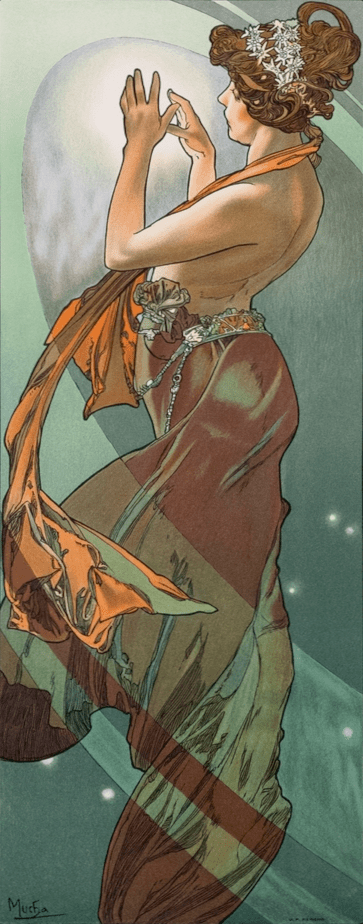

On the other hand, one may readily see from Venus’ orbit how She is associated with beauty:

This lovely lotus-like shape comes from looking at the solar system from above, and drawing a line between the positions of Venus and Terra each day for eight years. It occurs because the ratio between their orbital periods is extremely close—one might say suspiciously close—to 8/13.

Some of my other favorite astronomical coincidences are that Sol and Luna appear the same size as seen from Terra, and that each planet is approximately twice as far from Sol as the last.

When I first started working with geomancy and astrology, I conceived the houses as starting with the querent and working outward in distance as we went around the chart. That worked well enough, but I’ve been starting to properly study astrology and it occurs to me that I really missed the obvious. (Well, maybe not so obvious to us moderns; but at least literal.)

A horoscope is constructed of two main axes, the horizontal and the vertical. In astrology, this is quite literal: the horizontal axis is the ground, and the vertical axis stretches from heaven above to the underworld below, with earth sitting on the horizon itself. So the upper houses of the horoscope (VIII through XII) are literally spiritual (where everything happens but has no form), while the lower houses of the horoscope (II through VI) are literally material (where nothing happens but everything has form), and we human beings live on the boundary between the two. What’s more, the earth is constantly rotating, and this causes the ascendant (and therefore the houses) to rotate as well: so the eastern houses (I, II, III, XI, XII) are rising—in a sense, coming towards you, and consequently near—while the western houses (V through IX) are setting—in a sense, going away from you, and consequently far away. These all relate to oppositions: going 180° around the chart, you flip from material to spiritual and from near to far (or vice versa).

That gives us the angles, but what about the rest of the houses? Well, astrology is also intimately tied to aspect: the III, V, IX, and XI are in aspect (trine or sextile, as the case may be) to the ascendant, and so are considered to be working with the querent and therefore good; while the II, VI, VIII, and XII are not in aspect to the ascendant, and so are considered to be working at cross purposes to the querent and therefore bad.

So when you add all these up, what do you get?

Next, let’s flesh out that extremely abstract house system a bit. Because of the oppositional symmetry, I’d like to talk about the houses in pairs. This is convenient from an astrological perspective but not so much from a geomantic perspective; I’ll try to tie this all together from a geomantic perspective in a future post.

Finally, I want to discuss the planetary joys, since this is central to the understanding of the scheme presented above. Traditionally, fundamental to the understanding of the houses was the system of planetary joys, which indicate in which houses the planets rejoice. Chris Brennan goes into quite some detail in his book Hellenistic Astrology, but he also has an article freely available online which covers much the same ground. Briefly, though, each house was associated with a planet believed to have affinity with that house, and these associations are related to the meaning assigned to each of the houses above:

In the same way, the geomantic figures of each planet may be associated with those same houses. (In fact, Pietro d’Abano does exactly this in his fourteenth-century Handbook of Geomancy.) This leaves only the two figures that aren’t associated with a planet unaccounted for: Caput Draconis (associated with the ascending node) and Cauda Draconis (associated with the descending node). If you were paying close attention to the above, though, there is an obvious placement of these: the second and eighth houses have the exact same association of passing from one side of the ecliptic to the other! So we might associate ascending Caput with the rising second house, and descending Cauda with the setting eighth house. These seem especially apt, as Caput is associated with resources not yet put to use, and Cauda is associated with energies not yet finding expression. Further, the lunar nodes are traditionally considered malefic, due to their association with eclipses, and so “bad” houses would seem to be an appropriate placement for them.

So far, so good. But geomancy doesn’t simply use the astrological houses directly: it adds additional layers of meaning, as it adds three special houses (called “the court” and drawn in the center of the chart), and also inter-relates the meanings of certain houses. How do the astrological joys relate, then, to these additional meanings of the geomantic houses?

Let’s begin by looking at the four triplicities:

In all of these cases, the triplicities feel kind of like little slices of Maslow’s hierarchy: getting the material needs of the bottom tiers of the pyramid met allows one to move up and address higher and more spiritual needs. I think it is also notable that the first and third triplicities are both about you, while the second and fourth are about others: this is necessary because of the fractal nature of the chart; if it were not so, then these triplicities could not, themselves, be added together to form the witnesses.

And, speaking of the witnesses:

Finally, these in turn give rise to the judge, which is simply the Cosmos, as it is formed by the union of the microcosm with the macrocosm. This brings us full circle: the geomantic shield chart is no less a map of the universe than the astrological horoscope is; but while the astrological chart is oriented directionally (up/down, near/far), the geomantic chart is hierarchical (building from gross materiality up to spirituality and, eventually, to unity). But these two models are related, and one should always use the model more appropriate to the situation at hand.

So, summing all this up, the unified astrological and geomantic charts might look something like this:

| VIII ☋ Death | VII Earth | VI ♂ Misfortune | V ♀ Fortune | IV Underworld | III ☽︎ Impression | II ☊ Resources | I ☿ You |

| XII ♄ Curses | XI ♃ Blessings | X Heaven | IX ☉ Expression | ||||

| Left Witness Macrocosm | Right Witness Microcosm | ||||||

| Judge Cosmos | |||||||

I was pondering the Joys of the Geomantic Figures and realized something interesting: Mercury and Venus cannot rejoice together. This is because the first mother’s head must be latent if Mercury rejoices, the first daughter’s head must be active if Venus rejoices, and these cannot occur simultaneously.

I was curious if such a relationship held for any other pair of planets, and so I wrote a computer program to examine every geomantic chart and see which pairs of planets either always or never rejoice together. It turns out there is exactly one other possibility: the Sun and Jupiter also cannot rejoice together.

The analysis for this is a little more involved. Let’s name the boolean variables that make up the mothers as follows: A B C D for the first mother, E F G H for the second mother, etc.; the daughters are the transpose of these: A E I M for the first daughter, B F J N for the second daughter, etc.; and finally, the nieces are the XOR of their parents: A⊕E B⊕F C⊕G D⊕H, etc.; as in the following shield chart:

| D H L P | C G K O | B F J N | A E I M | M N O P | I J K L | E F G H | A B C D |

| C⊕D G⊕H K⊕L O⊕P | A⊕B E⊕F I⊕J M⊕N | I⊕M J⊕N K⊕O L⊕P | A⊕E B⊕F C⊕G D⊕H | ||||

| ... | ... | ||||||

| ... | |||||||

We will focus on the head and neck lines of the ninth house (where the Sun rejoices) and the eleventh house (where Jupiter rejoices). First, please note that the Solar figures Fortuna Major and Fortuna Minor always have identical head and neck lines, while the Jovial figures Acquisitio and Laetitia always have different head and neck lines. Therefore, if there is a Solar figure in the ninth house and a Jovial figure in the eleventh house, then A⊕E=B⊕F [eq. 1] and A⊕B≠E⊕F [eq. 2]. However, if we add B⊕E to both sides of eq. 1 and cancel, we get A⊕B=E⊕F [eq. 3]. Eqs. 2 and 3 cannot both be satisfied, therefore the Sun and Jupiter cannot rejoice together. ∎

When I asked her how she knows which dinosaur is which, my little daughter helpfully notes that Plesiosaurs always say, “please!” while that icthyosaurs always say, “ick!”

I feel like there is some sort of law of conservation of information that this world is beholden to: that the amount and kinds of information that can penetrate the veil between this world and the greater world beyond is limited. I like trying to poke at the boundary through the various tools I possess, but rarely do I get through.

The other day, I asked my deity in prayer a question along these lines. They said, “You know I can’t tell you that directly.” So I replied, “Can I ask about it with geomancy?” and They said, “You can always ask...”

You know where this is going just as well as I do.

See that Amissio (lack) connecting the seventh house (of my deity) and third house (of communication)? Yeah, that says, “...but I can’t tell you.”

I can almost see Them winking at me.

A bit over a month ago, I had a strange dream.

I was walking through a forested campsite, the kind you see in state parks all over New York. It was getting on towards evening. As I walked past a picnic table, I noticed it had what appeared to be a typeset page torn from an encyclopedia on it. I picked it up, and read, “Benevolent and malevolent beings come into existence in pairs, and so every benevolent spirit has it’s matching malevolent spirit, and vice versa. If one finds oneself so afflicted by a malevolent spirit, if one reaches out to its matching benevolent spirit, the two will recombine and cease to be.” Suddenly, night fell, and I heard a howl. I started running, and sure enough I was soon being chased by a wolflike creature: I couldn’t see it, but I could hear its heavy paws on the dirt, feel its hot breath on my back. Thinking of the page, I mentally called out to the wolf’s mirror-being and poof!—the wolf disappeared and I awoke.

Now, to be clear, the encyclopedia entry is just science fiction: spirits don’t appear and disappear like sentient particles and anti-particles. (At least, I’m pretty sure they don’t: it fits with no metaphysics of which I’m aware, and anyway my divinations on the topic have all said it’s just dream-logic.) But the basic idea of reaching out to a benevolent being to counter a malevolent one stuck with me. Different kinds of beings exist at different levels of consciousness: the states of love, hope, joy, and so on mix with the states of fear, uncertainty, doubt, and so on about as well as oil and water. If you can raise your consciousness, beings of lower states can’t touch you.

“Raising one’s state of consciousness” isn’t exactly an easy thing to do, but as a mystic, it’s something I’ve been practicing for nearly a decade now. I can’t say how, exactly, it works, but I know what it feels like and it’s something I regularly practice during prayer. (If I’m honest, I’m certain my deity’s doing most of the work, pulling me up much like I hoist my daughter onto my shoulders. Even so, it’s an exhausting state to maintain for long!)

Anyway, I wrote this all down in my diary, figured it was interesting if abstract, and filed it away. I didn’t think I’d ever have occasion to give it a try—but so I did!

Last night, I got up in the middle of the night last night to go to the bathroom, and when I came back into the bedroom, I had a feeling of something terrible watching me from the closet. The door was open, which was a little odd since I keep it closed, so I went over to close the door and I felt something of a horrible malice leering out at me from the darkness. I could almost see hungry eyes peering at me, long limbs hunched as if ready to pounce. I closed the door—this took some effort as my every reaction was to “get away”—and got back into bed. It wasn’t long before I felt the malevolent energy stalking over to the bed from the closet.

I remembered the dream I had, and the theorizing I had done around it, so I immediately began to pray and trying to raise my mental state to where it is when I meet my deity. This got quite a response: my deity said, “Hang on,” and waves of rage poured from the whatever-it-was, and I felt—literally felt, with my physical senses and not my spiritual ones—a violent and bitter tempest rage around me, but I felt safe and serene in the eye of the storm. It took effort to keep my mind focused on love and not fear—I’m naturally a very fearful person—but I held on to the mental state as best I could. After a minute or two, the wind subsided and the rage stalked away. As it did, I heard my deity say, “Good. Remember that trick,” and I drifted back to sleep.

What a strange experience! Prior to this, every spirit I’ve encountered has either been at best quite friendly, or at worst playfully neutral. It just goes to show, there really are monsters out there, and yes, sometimes they creep out of closets.

I tend to spend a lot of time in prayer each day. I’ve been pretty sick for the last couple months, but I was feeling strong enough today that I decided to get out for a walk while I did my prayers today. About halfway in, a few dogs streamed in from all over the neighborhood I was in and started following me as if I was the Pied Piper of Hameln. I went on praying and as I wound down, the dogs trailed off one at a time until I was left alone by the time I reached home again.

What a strange experience! I’ve never had that happened before, and I wondered if there was a connection to my prayers, or if there was a more mundane explanation.

I’m passionate Rubeus in the first. Normally, this is a pretty bad sign, as it’s an indicator that one isn’t thinking clearly, or is even engaged in self-deception. In this case, though, I think it’s simply showing that I was completely consumed in prayer, or perhaps, since Rubeus also occupies the fourth house (of private things), it indicates that my assumption that my prayers are private is quite mistaken! The quesited is shining Laetitia in the ninth house and occupying the third, indicating that yes, my prayers were in fact shining like a beacon for the neighborhood to see.

These perfect in three ways (which act as emphasis):

The dogs, as it happens, are masculine Puer in the sixth. (The largest dog, who was closest to me, was male, at least!) It is interesting that perfection also exists between me and the dogs, and between my prayer practice and the dogs, all facilitated through translations of receptive Populus.

I’m not clairvoyant, but this makes me wonder what the world looks like to one who is.

There is a game, called the Game of Life. It was invented by the mathematician John Conway in 1970. “Game” is perhaps a bit of a misnomer, since one doesn’t really “play” it: it’s more of a set of rules that, applied repeatedly, give rise to interesting patterns of behavior.

The gist of it is that the rules act as a sort of abstracted simulation of a petri dish: one has a grid, every square of which may possibly be occupied by a “cell.” The rules governing these cells are simple:

It turns out that these rules can give rise to very complex behavior. At the very low end, “creatures” made up of groups of cells can be made that “walk” around: the best known of these is called a glider. At the very high end, though, it’s been demonstrated that we can build a universal computer: this means that the Game of Life can carry out any algorithm we know how to make. (It turns out that the Game of Life is not “special” in this regard: simple systems of rules that can “do anything” are actually pretty common.)

How does this work? Well, the Game of Life provides a gridded substrate, a “universe” in which “creatures” made up of various combinations of cells can exist. We can build a more sophisticated substrate atop this one, though, using, say, some group of “creatures” repeated indefinitely across the grid, making a “meta-grid” made up of “meta-squares.” By pretending the new “meta-grid” is our normal grid, we have now made a new universe with new rules more amenable to whatever task we were trying to accomplish; the tradeoff, however, is that the original abitrary and freeform behavior of the old grid is gone, and replaced with a more fixed, clunkier, more sluggish meta-grid. An elegant example of this is a version of the Game of Life built within the Game of Life: it works exactly the same as the Game Life does (or any other game with similar rules, in fact), but it takes two thousand times as much space and thirty thousand times longer to do it.

And, of course, this process may be repeated, building a “meta-meta-grid” on top of the “meta-grid” you just built, and so on and so on: making ever more sophisticated universes, but also ever more fixed and sluggish.

Does this sound familiar? It reminds me an awful lot of the universe as described by occultism! There is an ultimate root reality, analagous to the pure rules of the Game of Life; but on top of that root reality, are various, denser “planes” of existence (each corresponding to a “meta-grid” or a “meta-meta-grid” or so on). These planes all give rise to the next, and so in a very real sense they overlap or interpenetrate each other. Very sophisticated beings at one level can mess with the building blocks used to create levels further down, thereby causing “miraculous” occurrences. Since they are made up of simpler parts, these “higher” beings—operating much more quickly—don’t experience time the way “lower” beings do. Indeed, “lower” beings have pieces on the “higher” planes, and once those pieces are self-stable, the scaffolding on the “lower” planes may indeed be pulled away without damaging the core structure within. This strikes me as a way where creatures within these planes slowly but surely modify the rules that the planes are subject to.

I should step back a moment and say that these—the Game of Life and occult metaphysics both—are merely metaphors for an underlying reality. But it’s interesting and suggestive to me that convergent evolution is at work: that these metaphors, coming from very different civilizations and domains of study, highlight similar properties.

As I mentioned earlier, these properties are not unique to the Game of Life: there are very many systems in computer science that exhibit similar properties. Stephen Wolfram, a well-known mathematician, is presently exploring even simpler games to accomplish the same thing. He says he’s trying to find the fundamental laws that underlie physics—and, naturally, physicists hate him for this, saying that what he’s doing has nothing to do with physics. I agree, in that it strikes me that he’s actually working on meta-physics.

Traditionally, in astrology, there are three ways in which planets are contrasted: the houses in which they rejoice, their zodiacal rulership, and their zodiacal exaltation. These three each refer to different ways in which a planet is empowered:

Each of these pairings showcases a different side of the planets. Let’s look at the rejoicing houses first:

Now, let’s look at the zodiacal rulerships:

Finally, let’s look at the zodiacal exaltations:

And so, to recap the associations of the planets: Luna is impressionable and nurturing and changing, Mercury is unusual and argumentative and intellectual, Venus is pleasurable and harmonious and sensual, Sol is expressive and charismatic and magnanimous, Mars is passionate and dominating and destructive, Jupiter is charitable and idealistic and orderly, and Saturn is deliberate and solitary and austere.

To be honest, the more I dig into astrology, the more amazed at how elegant it all is. Everything ties together into a neat whole with mathematical precision. I find all these mutually-reinforcing concepts incredibly helpful: I’ve lived an pretty lopsided life and have a lot of difficulty relating to or comprehending many things that people take for granted, but astrology gives so many interrelated systems to work from, there’s always a way to analogize something I don’t understand from something I do.

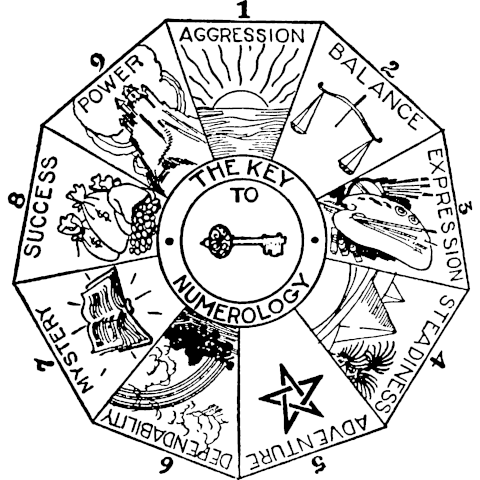

In the Gibson’s Complete Illustrated Book of the Psychic Sciences, there is a very fun chapter on numerology. It talks about how the names of things indicate their essential “vibration,” and how that energetic effect is brought to bear on the nature of the named thing. I was playing with this today and found it pretty successful at describing what I tested. (Which is pretty weird.)

Here’s one example. A bit over a decade ago, I started a small tech startup. It took a lot of hard work, but eventually we were quite successful, and I managed to sell the company last year just before the COVID panic broke the economy. In numerology, there are two important numbers associated with a thing: the date at which it was born, and the name by which it is known. I’ll describe both of my company’s numbers, below. (Apologies for omitting specifics, but I’d prefer to remain anonymous until my obligations to the acquiring company are complete.)

The date on which we first became known to the world reduces to the number 4. According to Gibson, “As a birth number, 4 stands for a steady, plodding nature, which always favors caution rather than risk. [...] Honesty and reliability are normal attributes with this birth number, but they hinge upon the satisfaction or security that the individual may gain from patience and perseverance.” Our company’s reputation was founded upon being easy-to-work-with, “low drama,” and reliable. Indeed, we were the only company in our industry with these attributes—as it turns out, each of our major competitors had the cloak-and-dagger birth number of 7—and this was the driver of our success.

The name by which we were known reduces to the number 8. According to Gibson, “As a name number, 8 spells Success with dollar signs ($UCCE$$). People expect big results from a person whose name is tuned to this powerful vibration. [...] The weakness with this name number lies in [...] wasted efforts and indulgence in small things when large opportunities are available.” As it happens, this was true on both sides: the company was notorious for failing to ship product, and yet we were financially successful despite ourselves. It is very likely we could have been two or three times as successful, had we not squandered so much effort!

I find these associations pretty interesting, and I wish I knew about them when I started the business: I might have picked numbers that were less serious and more fun! Still, I suppose exploring the occult aspects of it after-the-fact helps to make up for that, and I plan to play with numerology more as time goes on.

Thomas Taylor is the kind of person whose footnotes have footnotes.

We moderns—myself included!—lament the disenchantment of the modern world, the Age of Aquarius and the harsh rule of Saturn, the great gulf between the spiritual and the mundane, and so on.

But consider this: our pole star, Polaris, is an extremely good pole star, perhaps the best pole star: much closer to the celestial pole and much brighter than any other. Indeed, since it moves in the heavens, when Polaris becomes the pole star again many millennia hence, it will not be as good a pole star as it is now.

While our times are, perhaps, more difficult than most, we have the benefit of better guidance than most.

Let me excerpt an entry from my diary, dated Mar 2011:

While walking by my house today, there was a little leaf devil swirling in the road. I stepped past it, and it began to follow me, darting forward and back, playfully nipping at my heels. It spent ten minutes or so with me in this manner, all the way down the street: I leading, and it chasing. When I finally reached the end of the way and turned onto a side road to continue my walk, the leaf devil balked for a moment, spun in place, and finally whirled itself apart now that the game was over.

When I see such things with my own eyes, it is very difficult not to believe in magic.

I had completely forgotten about this lovely little incident, but was reminded of it by today’s chapter of Sallustius (§7), which speaks of circular motion being the imitation of Mind and linear motion being the imitation of Soul. We think very little of plain, old wind—but, for some reason, when the wind moves in circles, it seems intelligent, as my diary indicates!

So reminded, I thought I might ask if there was intelligence behind it, after all.

I’m Laetitia in the I, a figure of inspiration. The prospective spirit is Conjunctio in the VIII, the figure of forces coming together—and, I might note, a figure of Mercury, lord of intellect. Perfection exists through the translation (resolution by a third party, here Sallustius) of Fortuna Major (of success after long and patient effort) rejoicing in the IX (of philosophy) and in the XII (of blind spots). As a figure of the Sun, it’s almost as if He’s shedding light on the situation, and I would certainly say that taking ten years to make sense of an experience qualifies as long and patient effort!

The court takes a step back and looks at the bigger picture. At the time, I (Rubeus RW) was full of confusion and turmoil—I was just beginning, then, to take my first steps back into spirituality after harsh treatment at the hands of Christianity and materialism, both. This was soon to end (Cauda Draconis LW), but for the time being I was at a loss about the nature of the world (Amissio IV and J).

Puer in the III and XI seems to be my deity, winking and saying, “see how far I have led you?”

Let’s take Sallustius’ words as given and assume that the Gods are those beings that Cause but are not Caused. Therefore each God is an eternal fixed point, dependent only upon themselves.

Let’s also consider omniscience. A Mind, to understand something, must encode that information somehow. This can either be done directly (for example, our brains can be said to perfectly encode their own electrical signals, since that’s what they are), or indirectly (those electrical signals may encode sensory signals of external things). But this indirect form is a lossy process (“the map is not the territory”), which implies that the only way to be omniscient of something is to contain its original, since the alternative is to only have a lossy view of it (and a lossy comprehension cannot be considered complete).

But the Gods are not contained within each other—this would violate our original axiom. Thus the Gods cannot be omniscient—except, of course, in the aggregate, since they collectively give rise to the Cosmos. But there is no way to recover this collective information, as it is broken into disjoint spheres.

In a smaller sense, though, the Gods—even secondary or tertiary ones—can presumably be omniscient of something, if that something is within their causal sphere. Insofar as Apollo gives rise to Asclepius, Apollo is omniscient of Asclepius. Insofar as Asclepius gives rise to Hygeia, Asclepius is omniscient of Hygeia.

I think this lack of omniscience is an interesting consequence of polytheism, and helps make sense of both myth and everyday experience, where it appears that the Gods are “warring” with each other. The apparent conflict is a necessary consequence of the Gods being limited in their domains, but also collectively composing the definition of the cosmos.

Once upon a time, a traveler was walking a path in the wilderness when he heard, faintly, a cry for help. Following the sound, he found a wolf in a pit. “Please help me,” the wolf said, “I fell into this pit and can’t get out, and I’m terribly hungry and terribly frightened!” The traveler was a kindly man, so he found a log nearby and pushed it into the hole so that one end was at the bottom and the other was sticking out the top, like a ramp. The wolf climbed out, bared his fangs, and pounced on the man.

“Hey, what are you doing? I just saved your life!” the man said.

“But I’m safe now, and I’m hungry,” the wolf replied.

“But that’s not fair!” the man said. “You should always repay kindness with kindness.”

“That’s not how the world works,” the wolf replied. “Only the strong survive, and if that requires repaying kindness with harm, so be it!”

“No, no, that’s not right at all,” the man said. “Look, we need a second opinion to settle this. I’ll make a deal with you: let’s ask around, and if most agree with me, you will let me go; but if they agree with you, then you may eat me.” The wolf was a little bewildered by hunger and by the man’s persistence, so it agreed.

Near to the road was a great pine tree. “Excuse me,” it said, “but I couldn’t help but overhear your discussion. The man is right: kindness is repaid with kindness. Look in my branches: do you see all the birds here? I let them live under my shelter, and as thanks for this they spread my seeds far and wide. I have many children in the woods around here. Wolf, you should let the man go free.”

Soon, an ox came to graze nearby, and they asked him for his opinion on the matter. “The wolf is right: the world is unfair,” the ox said. “I have worked long and well for my master, but when I become too old to work anymore, he will kill and eat me. Is that a fitting payment for all my hard work? Wolf, you should eat the man and be done with it.”

Finally, a squirrel ran by. The man and the wolf called to the squirrel and explained their situation and asked her for her advice. “Wait, wait, wait, let me get this straight,” she said. “The man was in the hole and the log pushed the wolf in?” The man and the wolf told their story again and the squirrel said, “Oh, so the log was in the hole and the wolf pushed the man in?” And again the man and the wolf explained what happened. “Oh, it’s no good,” the squirrel said, “Can you just show me where you were?” And the exasperated wolf jumped back in the pit and the man went over to the road. “But wait,” the squirrel said, “There’s a log there, why didn’t the wolf just climb out?” And the man and the wolf explained that the log wasn’t there originally, and working together they pushed and pulled the log back out of the hole. “Oh, I see, I get it now,” said the squirrel, and as she scampered away, she said to the man, “I think that the wolf is right, and that you should be more careful who you help!”

“Ha! See?” said the wolf, “Now push that log back into the pit so I can eat you!” But the man had already left.

Those [Gods] who watch over [the world] are Hestia, Athena, and Ares. [... But] if there is no ordering power[, ...] whence comes the fact that all things are for a purpose[? ... To] attribute men’s acts of injustice and lust to Fate, is to make ourselves good and the Gods bad.

(Sallustius on the Gods and the World VI, IX; as translated by Gilbert Murray.)

Herostratus, an Ephesian, set fire to the temple of Artemis at Ephesus, which had been begun by Chersiphron, and completed by Demetrius and Paeonius. It was burnt on the same night that Alexander the Great was born, B. C. 356, whereupon it was remarked by Hegesias the Magnesian, that the conflagration was not to be wondered at, since the goddess was absent from Ephesus, and attending on the delivery of Olympias[. ...] Herostratus was put to the torture for his deed, and confessed that he had fired the temple to immortalize himself. The Ephesians passed a decree condemning his name to oblivion; but Theopompus embalmed him in his history, like a fly in amber.

(William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.)

Of Hestia, we barely remember the name of Chersiphron. Of Athena, we have forgotten the names of the judges. But of Ares, we remember well the name of Herostratus.

We may not like Ares, but that does not mean He is not Good, and neither does it mean He does not look after His own.

Any one who turns from the great writers of classical Athens, say Sophocles or Aristotle, to those of the Christian era must be conscious of a great difference in tone. There is a change in the whole relation of the writer to the world about him. The new quality is not specifically Christian: it is just as marked in the Gnostics and Mithras-worshippers as in the Gospels and the Apocalypse, in Julian and Plotinus as in Gregory and Jerome. It is hard to describe. It is a rise of asceticism, of mysticism, in a sense, of pessimism; a loss of self-confidence, of hope in this life and of faith in normal human effort; a despair of patient inquiry, a cry for infallible revelation; an indifference to the welfare of the state, a conversion of the soul to God. It is an atmosphere in which the aim of the good man is not so much to live justly, to help the society to which he belongs and enjoy the esteem of his fellow creatures; but rather, by means of a burning faith, by contempt for the world and its standards, by ecstasy, suffering, and martyrdom, to be granted pardon for his unspeakable unworthiness, his immeasurable sins. There is an intensifying of certain spiritual emotions; an increase of sensitiveness, a failure of nerve.

(Gilbert Murray, Five Stages of Greek Religion IV.)

If there is a better description of the transition from the age of Aries to the age of Pisces, I have not seen it.

The religions of the age of Aries, a fire sign, were characterized by orthopraxy: that is, one had to act in the right manner, but your inward beliefs were irrelevant. The religions of the age of Pisces, a water sign, by contrast, were characterized by orthodoxy: that is, one had to believe the right things, but how that was expressed was irrelevant.

In the same manner, I might propose that the religions of the age of Aquarius, an air sign, can be expected to be characterized by ortholexy, “right speaking:” one has to say the right things regardless of what you do or what you believe. One need only consider the popular movements of our time for ample example of this...

May I be no man’s enemy,

and may I be the friend of that which is eternal and abides.

May I never quarrel with those nearest to me;

and if I do, may I be reconciled quickly.

May I never devise evil against any man;

if any devise evil against me,

may I escape uninjured and without the need of hurting him.

May I love, seek, and attain only that which is good.

May I wish for all men’s happiness and envy none.

May I never rejoice in the ill-fortune of one who has wronged me. ...

When I have done or said what is wrong,

may I never wait for the rebuke of others,

but always rebuke myself until I make amends. ...

May I win no victory that harms either me or my opponent. ...

May I reconcile friends who are wroth with one another.

May I, to the extent of my power, give all needful help to my friends

and to all who are in want.

May I never fail a friend in danger.

When visiting those in grief

may I be able by gentle and healing words to soften their pain. ...

May I respect myself. ...

May I always keep tame that which rages within me. ...

May I accustom myself to be gentle,

and never be angry with people because of circumstances.

May I never discuss who is wicked and what wicked things he has done,

but know good men and follow in their footsteps.

(Eusebius (of Myndus?); as quoted by Stobæus; and as translated by Gilbert Murray, who notes, “there is more of it.” Stobæus does not appear to be well-translated into English; I should like to find a more complete translation of it.)

All content on amissio.net is dedicated into the public domain.